To estimate the prevalence of childhood obesity in Brazil by means of a systematic review of representative studies.

SourcesWe searched for population-based studies that assessed obesity in Brazilian children aged < 10 years in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus and other sources up to September, 2019. Paired researchers selected studies, extracted data and assessed the quality of these studies. Meta-analysis of prevalence and confidence interval (95% CI) was calculated, weighted by the population sizes using Freeman-Tukey double-arccosine transformation. Heterogeneity (I2) and publication bias were investigated by meta-regression and Egger’s test, respectively.

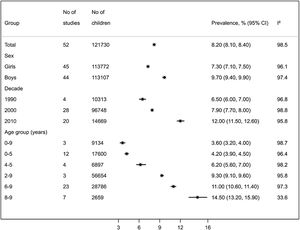

Summary of the findings53 studies were included (n = 122,395), which were held from 1986 to 2015 and limited mainly due to inadequate response rates. Prevalence of obesity in the three-decade period was of 8.2% ([95% CI]: 8.1–8.4%, I2 = 98.5%). Higher prevalence was observed in boys (9.7% [9.4–9.9%], I2 = 97.4%) than girls (7.3% [7.1−7.5%], I2 = 96.1%). Prevalence increased according to the decade (1990: 6.5% [6.0–7.0 %], I2 = 96.8%; 2000: 7.9% [7.7–8.0 %], I2 = 98.8%; 2010: 12.0% [11.5–12.6 %], I2 = 95.8%), and Brazilian region (Northeast: 6.4% [6.2−6.7%], I2 = 98.1%; North: 6.7% [6.3−7.2%], I2 = 98.8%; Southeast:10.6% [10.2−11.0%], I2 = 98.2%; South: 10.1 [9.7−10.4%], I2 = 97.7%). Heterogeneity was affected by age and region (p < 0.05) and publication bias was discarded (p = 0.746).

ConclusionFor every 100 Brazilian children, over eight had obesity in the three-decade period and 12 in each 100 had childhood obesity in more recent estimates. Higher prevalence occurred in boys, recent decades and more developed Brazilian regions.

Obesity affects 5% of children worldwide and increased by 20% from 1980 to 2015, with the highest prevalence in economically disadvantaged settings.1 This health risk accounted for 4 million deaths in 2015, mainly due to cardiovascular disease, and presents a high rate of associated morbidity in adult life.1 Measuring the prevalence of childhood obesity is crucial in tracking the trends of this health risk and establish public policies. <-- -->.

In Brazil - an emerging economy marked by high inequality -, nationwide surveys to assess obesity, especially in the pediatric population, have irregular frequency. Discrepancies between Brazilian regions as well as the effects of skin color and income were associated with the prevalence of childhood obesity in the most recent nationwide survey held in 2009.2 Since then, local studies have been carried out in different Brazilian cities and states,3 but no summarized representative estimates are available.

A systematic review with a meta-analysis is a valuable tool in this scenario. Although some reviews to summarize the obesity prevalence in Brazilian children by these methods have been conducted, the findings have limited validity, mainly due to the lack of representativeness,4–8 absence of quality assessment of primary studies4,6,9 and the use of an obsolete or irregular criteria for childhood obesity.4,9 We aimed to assess the national prevalence of childhood obesity in Brazil by means of a systematic review and meta-analysis of representative studies.

MethodsProtocol and registrationThe protocol containing the detailed methods of this systematic review was registered in the International prospective register of systematic reviews (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018091713).

Eligibility criteriaObservational or experimental representative studies that employed population or school-based sampling of children under 10 years old in Brazil were eligible. The prevalence of obesity in eligible studies relied on measured height and weight: studies with self-reported obesity were not eligible. Studies restricted to a particular ethnicity or social class were excluded.

Information sourcesWe searched the MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, LILACS, SciELO, and Brazilian nationwide theses and dissertations (Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel and repositories of Brazilian universities with a postgraduate program of collective health and nutrition) databases.

There were no language or publication status restrictions. We screened the references of relevant publications to identify additional potentially eligible studies.

SearchThe following search strategy was used for MEDLINE (via PubMed) and adapted for the other databases: (children OR child OR pediatric OR infant OR kid OR baby OR neonate OR childhood) AND (obesity OR overweight OR obese) AND (prevalence OR prevalencia) AND (Brazil OR Brasil), following the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies guidance.10 The search results in compatible formats were imported into the Covidence platform (www.covidence.org), for removing duplications and further review’s steps. Searches were held in January 2018 and updated in September 2019.

Study selectionIndependent paired researchers selected studies by screening titles and abstracts and then performing a full text assessment using the Covidence platform. A third reviewer arbitrated disagreements. For theses and dissertations, one reviewer screened the search results and eligibility was confirmed by a second researcher, using an Excel spreadsheet.

Data collection processData were extracted by two reviewers and independently confirmed by another using a standardized spreadsheet. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Study authors were contacted to obtain additional data if relevant data were not available in the reports or to clarify conflicting information included in different reports on the same study.

Data itemsWe extracted study data (author, data collection year, study design, sampling frame, publication type, and research location), population characteristics (age, sex, and number of children), and childhood obesity data of the total population and in each group, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for obesity in children from 0 to less than 5 years old11 and from 5 to less than 10 years old.12 For eligible studies that assessed obesity by different criteria, we either recalculated the prevalence from the original studies’ datasets using the WHO growth criteria11,12 or obtained new estimates that were as supplied by the authors.

Risk of bias in individual studiesPaired and independent researchers and confirmed by another, assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the checklist for prevalence data from the Joanna Briggs Institute,13 consisting of the items: (i) sample frame (official source), (ii) sampling (probabilistic or universal sampling), (iii) sample size (statistically calculated), (iv) setting and participants description (appropriately described), (v) coverage of data analysis (adequate coverage for different age and sex subgroups), (vi) methods for outcome measurement (WHO growth criteria),11,12 (vii) standardization of outcome measurement (weight and height measured by validated instruments), (viii) statistical analysis (analysis adjusted or with sample weighting), and (ix) response rate (low rate of refusals and losses). Reviewers assigned 1 point for each item attended by the studies, with a maximum score of 9 per study.

Summary measuresThe primary outcome was the prevalence of childhood obesity and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Secondary outcomes included the prevalence of childhood obesity in girls, boys, age groups, decade and Brazilian geographic regions (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast and South).

Synthesis of results and additional analysesWe used Stata (version 14.2) for all statistical analysis. Meta-analysis of proportions were calculated with Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation14 (metaprop command, ftt option) and weighted according to the official population size obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics for each period and location of the primary studies (www.ibge.gov.br). Heterogeneity was estimated by the assessment of inconsistency between studies (I2) and chi-squared tests, with a significance level of p < 0.10.

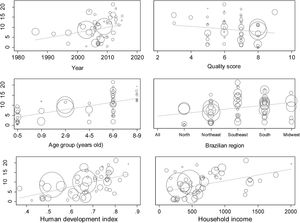

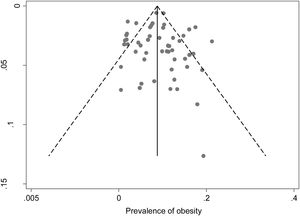

Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot asymmetry evaluation and Egger’s test (significance level of p < 0.05).15 Meta-regressions were calculated using the modified Knapp-Hartung method16 to investigate the effects of independent variables (age, region, year, and quality score) on the variability of obesity prevalence between studies. To better explain the effect of contextual factors in the outcome, meta-regressions of prevalence of obesity by human development index and household income of the locality and decade that each study was held as available at the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.

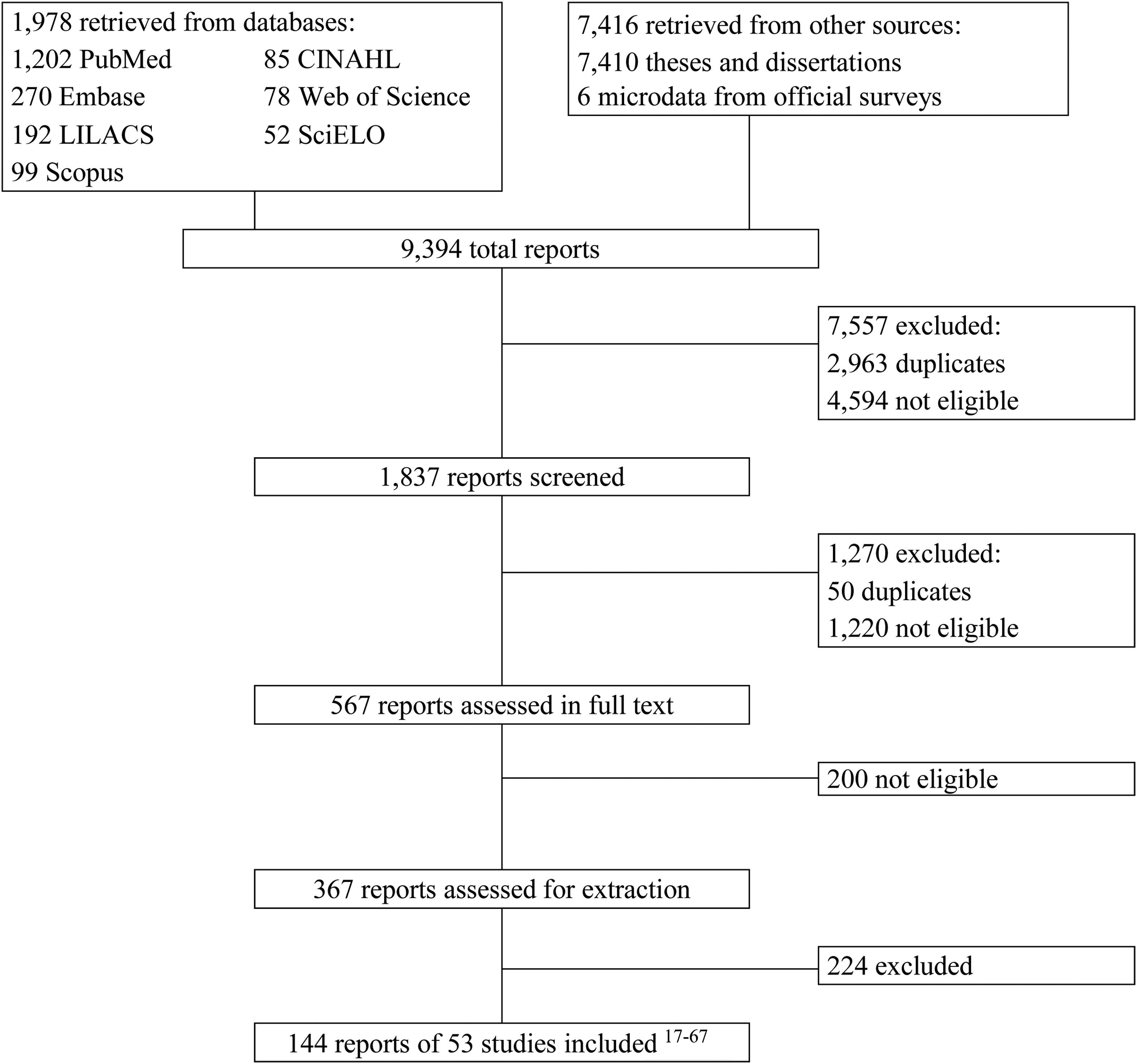

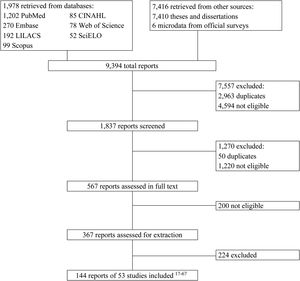

ResultsStudy characteristicsOut of 9,394 retrieved records, 567 were assessed in full text, and 143 reports from 53 studies were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).17–67 The references of all reports of included studies is listed in the Supplementary Material Appendix 1 and the reason for exclusion of the 222 studies assessed for data extraction is listed in Supplementary Material Appendix 2.

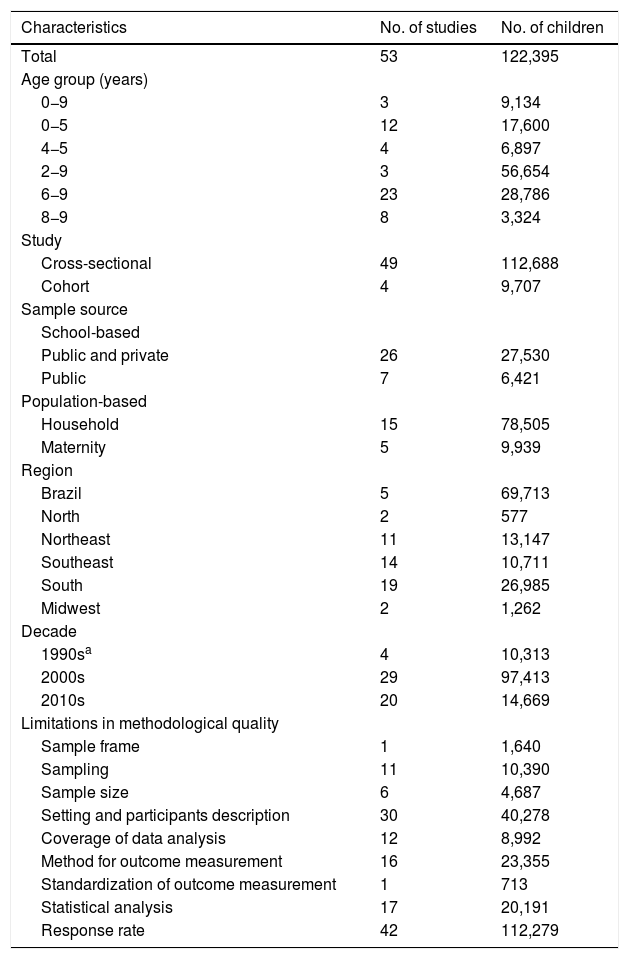

In total, 122,395 children were assessed in studies conducted between 1986 and 2015. Most of the studies were cross-sectional and school-based, conducted in the South and Southeast regions, and included children aged 6−9 years old (Table 1). Studies were limited mainly due to inadequate response rates, poor subject description and inappropriate statistical analyses. The quality assessment score ranged from 3 to 9 with a median of 7. The individual characteristics of each included study is depicted in the Supplementary Material Appendix 3. Upon our request from the authors, 36 studies sent additional data to allow proper quantitative synthesis.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Characteristics | No. of studies | No. of children |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 53 | 122,395 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 0−9 | 3 | 9,134 |

| 0−5 | 12 | 17,600 |

| 4−5 | 4 | 6,897 |

| 2−9 | 3 | 56,654 |

| 6−9 | 23 | 28,786 |

| 8−9 | 8 | 3,324 |

| Study | ||

| Cross-sectional | 49 | 112,688 |

| Cohort | 4 | 9,707 |

| Sample source | ||

| School-based | ||

| Public and private | 26 | 27,530 |

| Public | 7 | 6,421 |

| Population-based | ||

| Household | 15 | 78,505 |

| Maternity | 5 | 9,939 |

| Region | ||

| Brazil | 5 | 69,713 |

| North | 2 | 577 |

| Northeast | 11 | 13,147 |

| Southeast | 14 | 10,711 |

| South | 19 | 26,985 |

| Midwest | 2 | 1,262 |

| Decade | ||

| 1990sa | 4 | 10,313 |

| 2000s | 29 | 97,413 |

| 2010s | 20 | 14,669 |

| Limitations in methodological quality | ||

| Sample frame | 1 | 1,640 |

| Sampling | 11 | 10,390 |

| Sample size | 6 | 4,687 |

| Setting and participants description | 30 | 40,278 |

| Coverage of data analysis | 12 | 8,992 |

| Method for outcome measurement | 16 | 23,355 |

| Standardization of outcome measurement | 1 | 713 |

| Statistical analysis | 17 | 20,191 |

| Response rate | 42 | 112,279 |

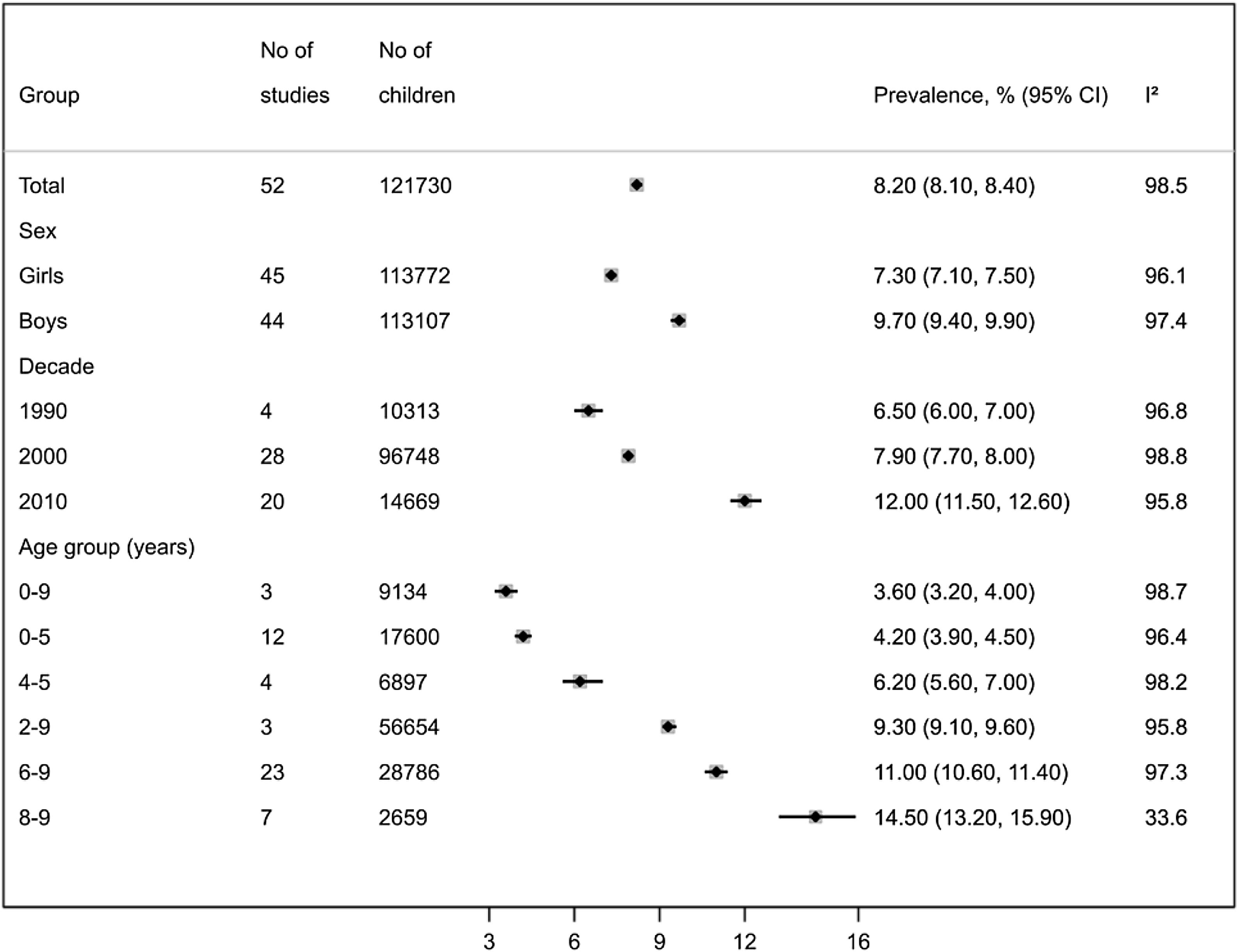

The overall prevalence of childhood obesity in this three-decade period was 8.2% ([95% CI]: 8.1–8.4%, I2 = 98.5%), lower in girls (7.3% [7.1−7.5%], I2 = 96.1%) than in boys (9.7% [9.4–9.9 %], I2 = 97.4%). Increasing trends in the obesity prevalence according to decade and age group were observed (Fig. 2). In the 2010s decade the prevalence was 12.0% ([11.5–12.60 %], I2 = 95.8%).

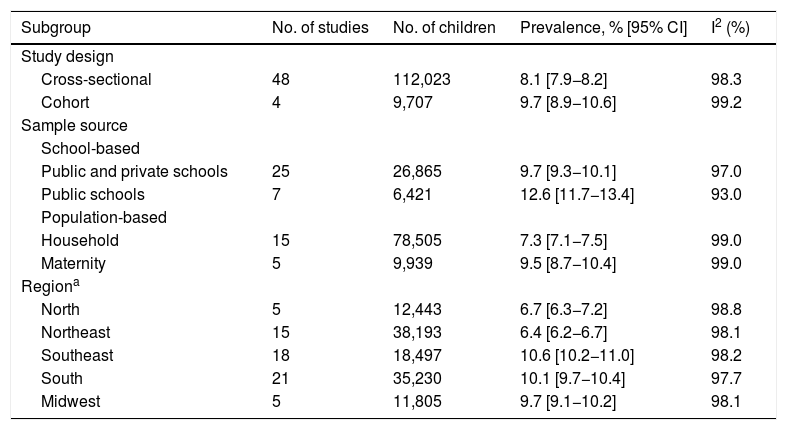

The highest prevalence rates of obesity were noted in the South (10.1% [9.7−10.4%], I2 = 97.7%) and Southeast (10.6% [10.2−11.0%], I2 = 98.2%) regions. Slightly lower obesity prevalence was observed in cross-sectional studies than in cohort studies, as well as in population-based studies rather than those in school-based studies (Table 2).

Prevalence of childhood obesity, 95% confidence interval (CI) and heterogeneity (I2) according to the study design, sample source and region of studies.

| Subgroup | No. of studies | No. of children | Prevalence, % [95% CI] | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 48 | 112,023 | 8.1 [7.9−8.2] | 98.3 |

| Cohort | 4 | 9,707 | 9.7 [8.9−10.6] | 99.2 |

| Sample source | ||||

| School-based | ||||

| Public and private schools | 25 | 26,865 | 9.7 [9.3−10.1] | 97.0 |

| Public schools | 7 | 6,421 | 12.6 [11.7−13.4] | 93.0 |

| Population-based | ||||

| Household | 15 | 78,505 | 7.3 [7.1−7.5] | 99.0 |

| Maternity | 5 | 9,939 | 9.5 [8.7−10.4] | 99.0 |

| Regiona | ||||

| North | 5 | 12,443 | 6.7 [6.3−7.2] | 98.8 |

| Northeast | 15 | 38,193 | 6.4 [6.2−6.7] | 98.1 |

| Southeast | 18 | 18,497 | 10.6 [10.2−11.0] | 98.2 |

| South | 21 | 35,230 | 10.1 [9.7−10.4] | 97.7 |

| Midwest | 5 | 11,805 | 9.7 [9.1−10.2] | 98.1 |

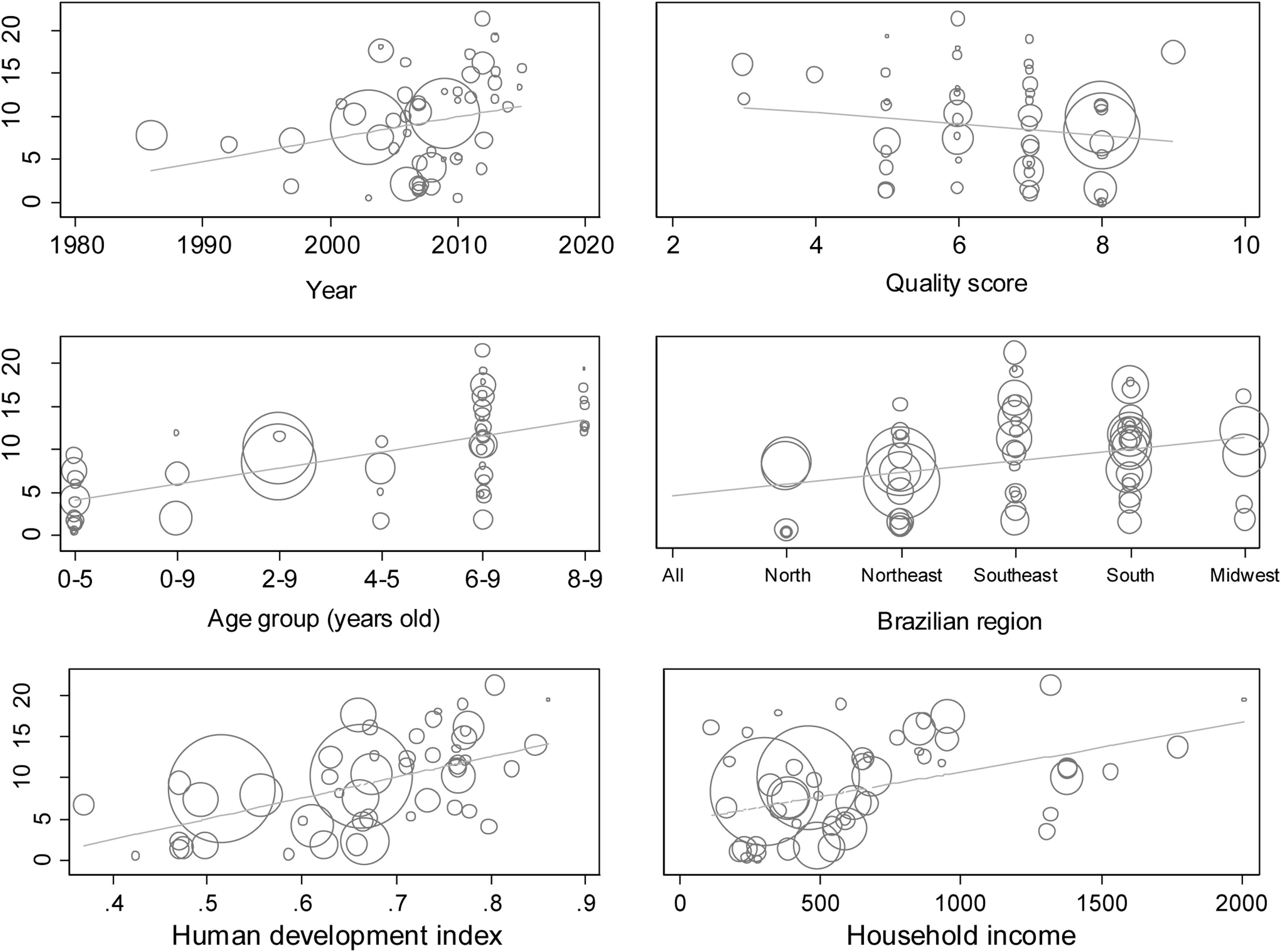

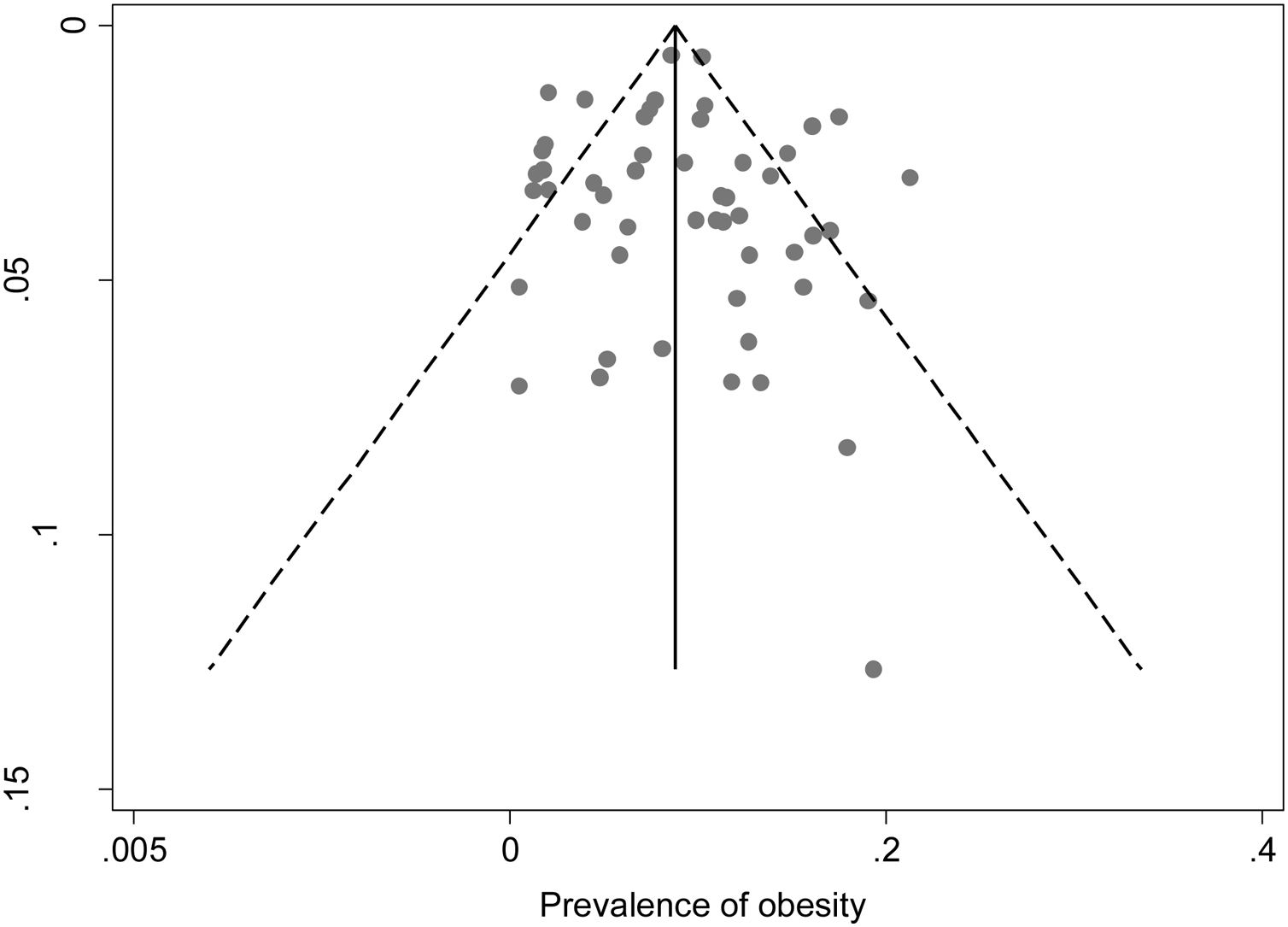

The variability in the obesity prevalence was significantly affected by the children’s age group (p < 0.001; residual I2 = 56.4%) and Brazilian region (p = 0.018; residual I2 = 63.4%), but not by the year of research (p = 0.051; residual I2 = 71.2%) and the methodological quality score of the studies (p = 0.256; residual I2 = 72.6%) (Fig. 3). Human development index (p < 0.001; residual I2 = 66.7%) and household income (p = 0.001; residual I2 = 66.1%) were positively associated to prevalence of obesity, also partially explaining the heterogeneity. A symmetric distribution was noted in the funnel plot, without evidence of a small studies effect on childhood obesity (p = 0.746) (Fig. 4).

For every 100 Brazilian children assessed in this three-decade period, more than eight children had obesity and 12 in each 100 had obesity in the 2010s decade according to this systematic review and meta-analysis of representative studies. Obesity was slightly more frequent in boys than in girls, and all estimates were heterogeneous. The prevalence increased with age, decade, and Brazilian regions, partially explaining the high variability across the conducted studies.

The results were highly inconsistent among the studies, which is a common limitation in meta-analysis of prevalence.68 Subgroup analyses according to factors that significantly affected heterogeneity did not lead to more homogeneous estimates. Estimates were calculated from studies with population representativeness that used the same official criteria for assessing obesity in the Brazilian pediatric population.11,12

Boys had a slightly higher prevalence of obesity than girls in Brazil; this pattern was similar to those in Latin American and Caribbean regions in 2016, with 13% of obesity in boys and 10% in girls aged 5–19 years,69 and in countries with a high-middle sociodemographic index according to the worldwide burden of obesity in 2015; however, this pattern was not observed in the overall childhood estimate.1 An inverse association was observed in a systematic review of Australian studies conducted between 1967 and 2012, with a higher prevalence of combined overweight and obesity in girls (21%) than in boys (18%) aged 2–18 years.70

The age-standardized mean body mass index of children and adolescents increased globally from 1975 to 2016 (an increase of 0.32 kg/m2 per decade for girls and 0.40 kg/m2 per decade for boys).71 Projections of global childhood obesity estimated that 5.4% of the population aged 5–18 years will have obesity by 2025, a 0.5% increase in relation to 2013.72 This trend seems to be influenced by human development in the region. Inverse associations between socioeconomic status and overweight and obesity were observed in a systematic review of 30 studies.73 In Spain, a cohort study including 1.1 million children showed a slight reduction in childhood excess weight, from 42% in 2006 to 40% in 2016,74 indicating the possible lower influence of time in highly developed regions.

The highest obesity prevalence was observed in more economically developed Brazilian regions, which also comprised the largest number of investigations. A bibliometric analysis of scientific obesity research studies from 1988 to 2007 revealed this tendency in few publications from Latin America in relation to more developed countries, with positive association between prevalence and the number of publications.75 Investigation of contextual factors showed that prevalence of childhood obesity was higher in settings of higher human development index and household income, which may reveal more access to food but not adequate nutrition. The nutritional transition to the consumption of ultra-processed foods accounted for approximately 40% of the total daily intake in children aged 6 years in a birth cohort in southern Brazil,76 compared to a cohort in the city of São Luís in the Northeast which is a less developed region, estimated in 26% of total calories of children up to 3 years old in 2007.77

Cohort studies reported a higher prevalence rate than cross-sectional studies, even though the latter were more frequent. Cohort studies are expensive due to the time required for follow-up and the large sample size, a possible explanation for the lower number of studies included, and are more prone to losses of follow-up than other types of studies.78

School-based studies had a higher prevalence and were more common than population-based studies, possibly due to more convenient logistic in recruiting and data collection of children. Absenteeism during data collection in school-based research studies may explain higher prevalence observed. An analysis of 1,069 students in fourth to sixth grade in nine public elementary schools in Philadelphia in a published 2007, reported that children with obesity were absent (12.2 ± 11.7 days) more frequently than healthy children (10.1 ± 10.5 days),79 showing a possible difference in school attendance that could result in selection bias. In Brazil, absenteeism and the lack of universal education for children can be due to the effects of economic crises and increasing poverty, resulting in an increase in male child labor in 2015 compared to 2013 in both rural and urban areas.80

ConclusionOver eight out of every 100 Brazilian children up to 10 years old had obesity in the three-decade period of this comprehensive analysis of representative studies and 12 in each 100 children had obesity in the 2010s decade. Obesity was higher in boys than in girls and increased with age, decade, and in more developed Brazilian regions. Further investigation should take into account underlying factors such as dietary patterns and inequalities across different Brazilian regions.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FundingThis research was funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) [grant number: 440865/2017-4]. Galvao TF receives a productivity scholarship from CNPq [grant number: 3064482017-7].

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank Raisa Rafaela Santos de Gusmão for the contribution in piloting the selection and data extraction of studies, and the authors of eligible manuscripts for providing data or clarification upon our request: Adriana Paula Silva, Alanderson A. Ramalho, Alessandra Doumid Borges Pretto, Alessandra Vitorino Naghettini, Alynne Christian Ribeiro Andaki, Ana Flavia Granville-Garcia, Ana Mayra A. de Oliveira, Ana Paula Carlos Cândido Mendes, Anna Christina Barreto, Anne Jardim-Botelho, Barbara H. Lourenço, Carla de Oliveira Bernardo, Cassiano Ricardo Rech, Cézane Priscila Reuter, Denise Petrucci Gigante, Deysianne Costa das Chagas, Diego Moura Tanajura, Elenir Rose Jardim Cury Pontes, Elma Izze da Silva Magalhães, Emil Kupek, Fabian Calixto Fraiz, Felipe S. Neves, Gabriella Bettiol Feltrin, Gerson Luis de Moraes Ferrari, Haroldo da Silva Ferreira, Ida Helena Carvalho Francescantonio Menezes, Jéssica Pedroso, Julia Khede Dourado Vila, Juliane Berria, Lana do Monte Paula Brasil, Larissa da Cunha Feio Costa, Leonardo Pozza Santos, Lucia Yassue Tutui Nogueira, Luciana Neri Nobre, Marcela de França Verçosa, Marcos Britto Correa, Marcos Pascoal Pattussi, Maria Luiza Kraft, Maria Wany Louzada Strufaldi, Naruna Pereira Rocha, Nilton Rosini, Patrícia Casagrande Dias de Almeida, Paula Azevedo Aranha Crispim, Peter Katzmarzyk, Rosângela de Mattos Müller, Ruth Liane Henn, Samuel Carvalho Dumith, Silvia Diez Castilho, Sílvia Letícia Alexius, Silvia Nascimento de Freitas, Silvia Regina Dias Medici Saldiva, Simone Augusta Ribas, Suélen Henriques da Cruz, Valter Cordeiro Barbosa Filho, Wendell Bila.

Research datasetThe dataset of this research is fully available at: https://osf.io/f2qnp.

Study conducted at Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Campinas, SP, Brazil.