Pone et al., in a study published in this Journal, have attempted to identify historical or observable signs or symptoms that reliably predict worsening of dengue disease in children.1 In so doing, they have coined a new term “serious dengue disease” and adopted a new clinical outcome metric, “treatment modality.” The “treatment modalities” chosen include administration of “amines, inotropes, colloids, mechanical ventilation, non-invasive ventilation, peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis.” Lethargy, abdominal distension, pleural effusion, and hypoalbuminemia were the most reliable markers of serious dengue disease identified in 145 children hospitalized in Rio de Janeiro in 2007–2008, who had direct or indirect evidence of recent dengue infection. The authors are among those who would agree that a more accurate identification of dengue predictors would best be derived from large protocol-based prospective studies of physiologically characterized laboratory confirmed dengue illnesses.

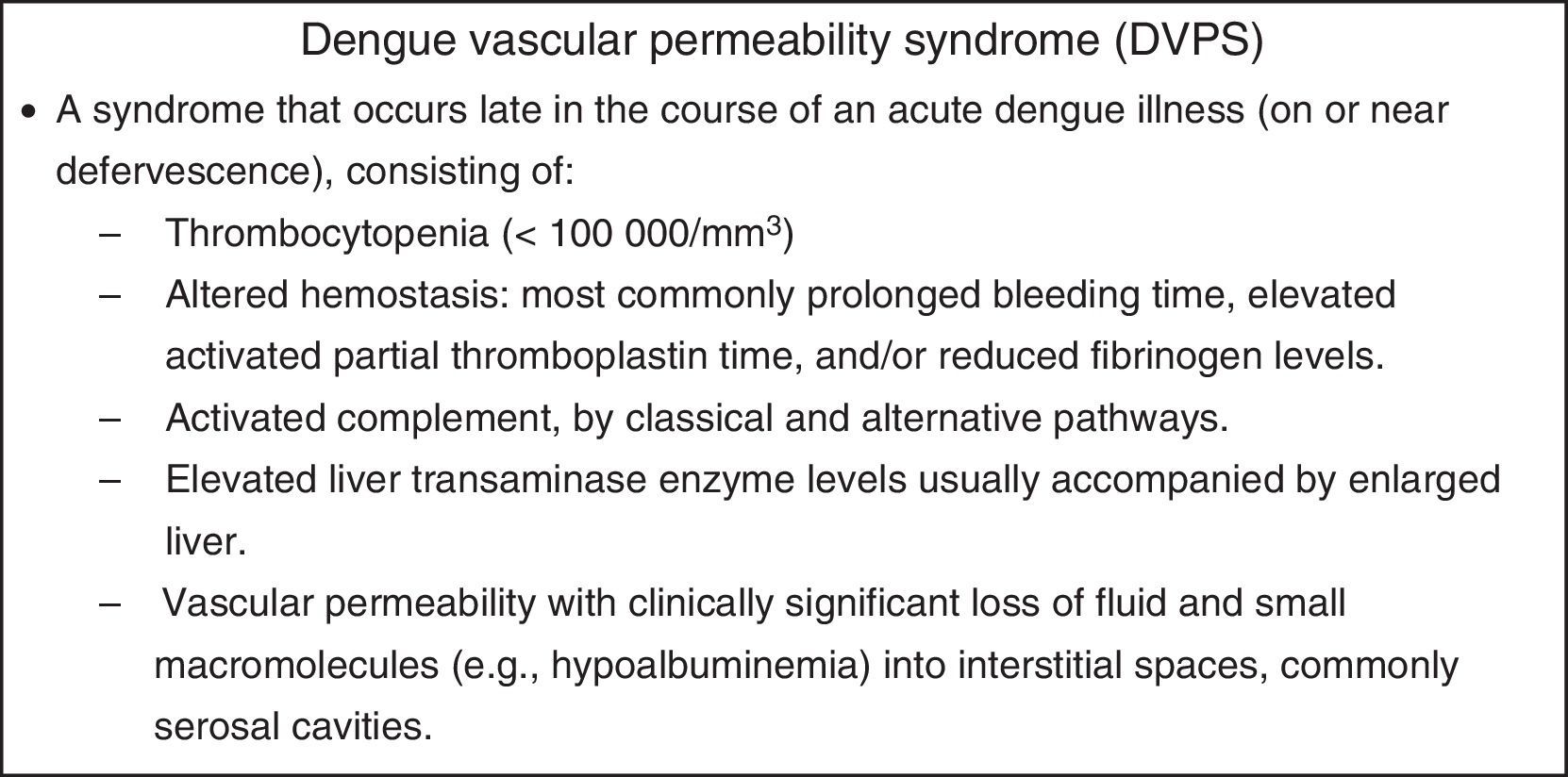

There is considerable historical precedent for this effort. Ever since the 1950s, when it was recognized that dengue viruses caused a severe and often fatal acute febrile disease of children, it has been the goal of researchers to describe the pathophysiology of dengue disease aiming to provide better treatment and to identify predictive early warning markers to improve triage.2,3 This was the motivation behind the creation of the case definitions, dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS), in wide use since their adoption by WHO in 1975, and the new case definitions introduced in 2009.4,5 In the 1960s, dengue research programs in Southeast Asia found that children were dying of a new clinical entity, the dengue vascular permeability syndrome (DVPS; Fig. 1), characterized by a complex of physiologic abnormalities affecting multiple organ systems including the liver, blood coagulation, complement, hematopoiesis, serum proteins, and the vascular system that reach a maximal expression at defervescence.3,6–10 It soon was well understood that children with DVPS benefitted from early, physiologically relevant fluid resuscitation.6 It was also observed that the fluid leak varied in severity from child to child and that a physiologically irreversible penalty might occur in just a matter of hours due to failure to maintain adequate blood volume.5,11–13

The signs and symptoms of dengue and DVPS change from day to day. Those that precede shock have been identified as “warning signs.” Warning signs of dengue infections were described long ago. Siler and Simmons, who recorded daily clinical and laboratory features of several hundred experimental dengue illnesses mostly in seronegative young adult male US Army volunteers, observed a profound mid-illness dengue leukopenia.14,15 More importantly, they found this leukopenia consisted of two components, a reduction in circulating lymphocytes and a destruction of mature polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The latter produced a diagnostic “cross,” where there were greater numbers of immature than mature polys in blood smears.15 It has been speculated that leukopenia and thrombocytopenia might be related to a remarkable phenomenon that regularly occurs in dengue infections before the onset of fever, a profound suppression of all cellular elements in the bone marrow.16,17 In Thailand, three early warning signs were used in patient triage: thrombocytopenia and a positive tourniquet test were thought to herald dengue vascular permeability, while a fingertip microhematocrit was taken to establish a baseline value to monitor hemoconcentration.18 Because platelet numbers decline and hematocrits rise quickly, multiple measurements must be performed and disease severity eventually is most accurately scored using modal high or low values. Some workers found that high levels of aspartate aminotransferase identified those children who proceeded to DVPS.18 Careful physiological characterization of dengue illnesses in children has resulted in significant improvement in treatment and sharply reduced case fatality rates.11,19

There has been considerable disagreement about the utility of most warning signs or laboratory tests in wide use for predicting the outcome of dengue infections.20 One approach to identify predictors has been to look for universal components in DSS. A meta-analysis identified the significant associations of shock as age, female sex, neurological signs, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemoconcentration, ascites, pleural effusion, hypoalbuminemia, hypoproteinemia, hepatomegaly, levels of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase, thrombocytopenia, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, primary/secondary infection, and DENV-2.21 The vast expansion of dengue infection globally has placed great stress on clinical facilities, generating further efforts to improve patient triage by validating early warning signs.22–25 One such study will enroll 7000–8000 children with a febrile disease who are admitted to outpatient departments in eight dengue-endemic countries.22 This large prospective study, now in progress, includes three sites in Brazil. As of December 2015, a total of 7096 participants had been enrolled, with dengue confirmed in 2510/5996 (42%). Enrolment will continue until June 2016. It is hoped that sufficient numbers of children with acute dengue infections will proceed on to severe dengue, providing unequivocal laboratory or clinical predictors, specifically for DSS.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares no conflicts of interest.