This study aimed to assess the quality of systematic reviews on prevention and non-pharmacological treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents.

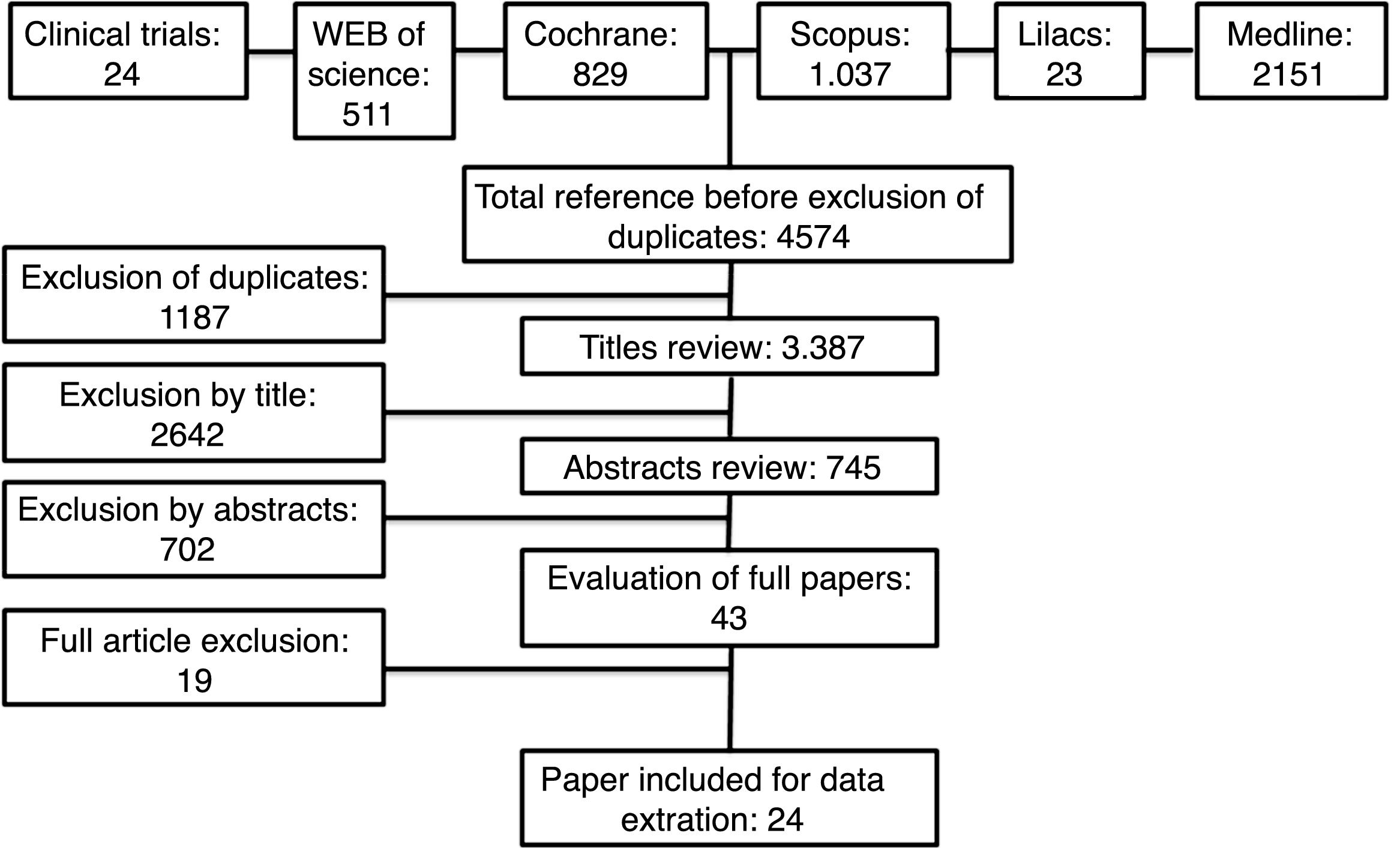

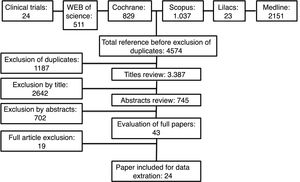

Data sourceA search was done in electronic databases (Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, LILACS, the Cochrane Library, and Clinical Trials), including only systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Reviews were selected by two researchers, and a third one solved the divergences. PRISMA statement and checklist were followed.

Summary of dataA total of 4574 records were retrieved, including 24 after selection. Six reviews were on obesity prevention, 17 on obesity treatment, and one on mixed interventions for prevention and treatment of obesity. The interventions were very heterogeneous and showed little or no effects on weight or body mass index. Mixed interventions that included dieting, exercise, actions to reduce sedentary behavior, and programs involving the school or families showed some short-term positive effects. Reviews that analyzed cardiovascular risk factors demonstrated significant improvements in the short-term.

ConclusionThe systematic reviews of interventions to prevent or reduce obesity in children and adolescents generally showed little or no effects on weight or body mass index, although cardiovascular profile can be improved. Mixed interventions demonstrated better effects, but the long-term impact of obesity treatments of children and adolescents remains unclear.

Este estudo teve como objetivo avaliar a qualidade das revisões sistemáticas sobre prevenção e tratamento não farmacológico do sobrepeso e da obesidade em crianças e adolescentes.

Fontes de dadosFoi realizada uma busca em bases de dados eletrônicas (Medline via Pubmed, Web of Science, Scopus, LILACS, The Cochrane Library e Ensaios Clínicos), incluindo apenas revisões sistemáticas com meta-análise. As revisões foram selecionadas por dois pesquisadores e um terceiro resolveu as divergências. A lista de recomendações do PRISMA foi seguida.

Síntese dos dadosForam identificados 4.574 publicações, e 24 foram incluídas após a seleção. Seis publicações eram sobre prevenção da obesidade, 17 sobre tratamento da obesidade e 1 sobre intervenções mistas para prevenção e tratamento da obesidade. As intervenções eram muito heterogêneas e mostraram pouco ou nenhum efeito sobre o peso ou índice de massa corporal. Intervenções mistas que incluíam dieta, exercícios, ações para reduzir o comportamento sedentário e programas que envolviam a escola ou as famílias mostraram alguns efeitos positivos de curto prazo. Revisões que analisaram fatores de risco cardiovascular demonstraram melhoras significativas em curto prazo.

ConclusãoAs revisões sistemáticas de intervenções para prevenir ou reduzir a obesidade em crianças e adolescentes geralmente mostraram pouco ou nenhum efeito sobre o peso ou índice de massa corporal, embora o perfil cardiovascular possa ter melhorado. Intervenções mistas demonstraram melhores efeitos, mas o impacto em longo prazo dos tratamentos da obesidade de crianças e adolescentes ainda não está claro.

Obesity is now responsible for about 5% of all deaths worldwide.1 If its prevalence continues on its current trajectory, almost half of the world's adult population will be overweight or obese by 2030.1 Obesity is one of the top three global social burdens generated by human beings, along with smoking and armed violence,2 and has huge personal, social, and economic costs for society and all healthcare systems.3 The prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity has increased substantially worldwide in less than one generation. Some low- and middle-income countries have reported similar or more rapid rises in childhood obesity than high-income countries, despite continuing high levels of undernutrition.4–6

The global age-standardized prevalence of obesity increased from 0.7% in 1975 to 5.6% in 2016 in girls, and from 0.9% in 1975 to 7.8% in 2016 in boys.7 This increasing prevalence of childhood obesity is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular risk factors, adult obesity, and obesity-related comorbidities.8,9 There is an urgent need to identify effective preventive and therapeutic interventions that can be targeted at children, families, the entire population, and in the obesogenic environment.10

In order to clarify the available scientific evidence regarding prevention and treatment of obesity in children and adolescents, the authors conducted a quality assessment of all systematic reviews with meta-analysis published so far and summarized the results.

MethodsSearch strategyThe search was performed in the following electronic databases: Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, LILACS, The Cochrane Library, and Clinical Trials.

The selection of the descriptors used was made through MeSH consultation (Pubmed's Medical Subject Headings). The search was performed in English, until October 26th 2017, and three blocks of concepts were used: the first, with terms related to obesity and to non-pharmacological treatments for obesity; the second, with terms related to the type of the study design (trial, random*); and the third, terms related to the age group of interest (adolescent*, child*, preschool*, school*; Supplementary Table S1). The search was not restricted by date or sample size.

The standardized PICO statement is showed below:

P – Obesity or overweight, children and adolescents

I – Any intervention, except pharmacological treatment

C – No intervention

O – Body mass index (BMI), weight, waist circumference, and cardiovascular risk factors

The criteria for the inclusion of articles were as follows: (a) studies evaluating non-pharmacological interventions for weight loss or prevention of obesity in children or adolescents with overweight or overweight/obesity (b) systematic review with meta-analysis. The exclusion criteria were studies that did not perform a meta-analysis of the results. The articles were selected by two reviewers (GAA and LAB), initially based on reading of the title, then on reading of the abstracts, and subsequently the full articles. In case of disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer had the final decision on inclusion (LB). The bibliographic references of the studies found in these databases were also reviewed.

The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and checklist for reporting this systematic review.11

Quality and risk-of-bias assessmentThe Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) was used in order to evaluate quality of the evidence, as it has been widely accepted and utilized by professional health care institutions, and is well known for its reliability and reproducibility (Supplementary Table S2).12 AMSTAR 2 consists of 16 items in a total and assess the degree of confidence in the results of systematic reviews. The tool does not generate a quality score, but a recommendation of a higher or lower confidence level in the results.

The articles were evaluated by two reviewers (CWS and KS); in case of disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer had the final decision (LB).

ResultsOverall, 4574 records were retrieved; after exclusion of duplicates and non-eligible titles, 24 systematic reviews were included. Six reviews did not meta-analyse their results and were therefore excluded.13–18 A detailed flowchart of study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. The reviews were classified based on the preventive or treatment approach and the results were presented considering this classification.

The main characteristics of the 24 included studies are described in Tables 1–5. Only four (16.7%) studies were classified as high quality review, almost 80% (n=19) of studies included were considered as critically low quality review (n=7) or low quality review (n=12). The AMSTAR 2 answers for each study are available as a supplement (Supplementary Table S2).

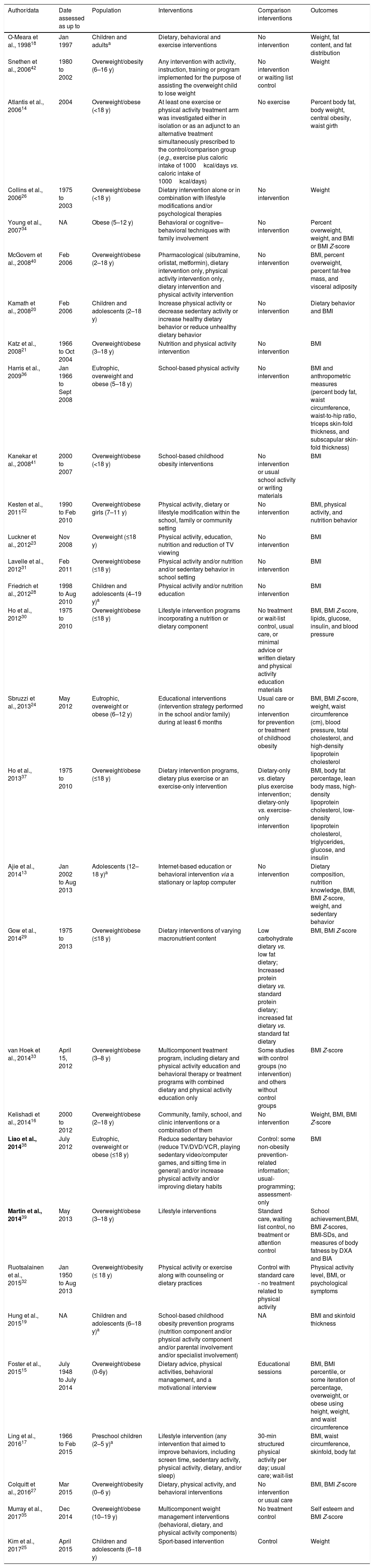

Characteristics of all included reviews.

| Author/data | Date assessed as up to | Population | Interventions | Comparison interventions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-Meara et al., 199818 | Jan 1997 | Children and adultsa | Dietary, behavioral and exercise interventions | No intervention | Weight, fat content, and fat distribution |

| Snethen et al., 200642 | 1980 to 2002 | Overweight/obesity (6–16 y) | Any intervention with activity, instruction, training or program implemented for the purpose of assisting the overweight child to lose weight | No intervention or waiting list control | Weight |

| Atlantis et al., 200614 | 2004 | Overweight/obese (<18 y) | At least one exercise or physical activity treatment arm was investigated either in isolation or as an adjunct to an alternative treatment simultaneously prescribed to the control/comparison group (e.g., exercise plus caloric intake of 1000kcal/days vs. caloric intake of 1000kcal/days) | No exercise | Percent body fat, body weight, central obesity, waist girth |

| Collins et al., 200626 | 1975 to 2003 | Overweight/obese (<18 y) | Dietary intervention alone or in combination with lifestyle modifications and/or psychological therapies | No intervention | Weight |

| Young et al., 200734 | NA | Obese (5–12 y) | Behavioral or cognitive–behavioral techniques with family involvement | No intervention | Percent overweight, weight, and BMI or BMI Z-score |

| McGovern et al., 200840 | Feb 2006 | Overweight/obese (2–18 y) | Pharmacological (sibutramine, orlistat, metformin), dietary intervention only, physical activity intervention only, dietary intervention and physical activity intervention | No intervention | BMI, percent overweight, percent fat-free mass, and visceral adiposity |

| Kamath et al., 200820 | Feb 2006 | Children and adolescents (2–18 y) | Increase physical activity or decrease sedentary activity or increase healthy dietary behavior or reduce unhealthy dietary behavior | No intervention | Dietary behavior and BMI |

| Katz et al., 200821 | 1966 to Oct 2004 | Overweight/obese (3–18 y) | Nutrition and physical activity intervention | No intervention | BMI |

| Harris et al., 200936 | Jan 1966 to Sept 2008 | Eutrophic, overweight and obese (5–18 y) | School-based physical activity | No intervention | BMI and anthropometric measures (percent body fat, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, triceps skin-fold thickness, and subscapular skin-fold thickness) |

| Kanekar et al., 200841 | 2000 to 2007 | Overweight/obese (<18 y) | School-based childhood obesity interventions | No intervention or usual school activity or writing materials | BMI |

| Kesten et al., 201122 | 1990 to Feb 2010 | Overweight/obese girls (7–11 y) | Physical activity, dietary or lifestyle modification within the school, family or community setting | No intervention | BMI, physical activity, and nutrition behavior |

| Luckner et al., 201223 | Nov 2008 | Overweight (≤18 y) | Physical activity, education, nutrition and reduction of TV viewing | No intervention | BMI |

| Lavelle et al., 201231 | Feb 2011 | Overweight/obese (≤18 y) | Physical activity and/or nutrition and/or sedentary behavior in school setting | No intervention | BMI |

| Friedrich et al., 201228 | 1998 to Aug 2010 | Children and adolescents (4–19 y)a | Physical activity and/or nutrition education | No intervention | BMI |

| Ho et al., 201230 | 1975 to 2010 | Overweight/obese (≤18 y) | Lifestyle intervention programs incorporating a nutrition or dietary component | No treatment or wait-list control, usual care, or minimal advice or written dietary and physical activity education materials | BMI, BMI Z-score, lipids, glucose, insulin, and blood pressure |

| Sbruzzi et al., 201324 | May 2012 | Eutrophic, overweight or obese (6–12 y) | Educational interventions (intervention strategy performed in the school and/or family) during at least 6 months | Usual care or no intervention for prevention or treatment of childhood obesity | BMI, BMI Z-score, weight, waist circumference (cm), blood pressure, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| Ho et al., 201337 | 1975 to 2010 | Overweight/obese (≤18 y) | Dietary intervention programs, dietary plus exercise or an exercise-only intervention | Dietary-only vs. dietary plus exercise intervention; dietary-only vs. exercise-only intervention | BMI, body fat percentage, lean body mass, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin |

| Ajie et al., 201413 | Jan 2002 to Aug 2013 | Adolescents (12–18 y)a | Internet-based education or behavioral intervention via a stationary or laptop computer | No intervention | Dietary composition, nutrition knowledge, BMI, BMI Z-score, weight, and sedentary behavior |

| Gow et al., 201429 | 1975 to 2013 | Overweight/obese (≤18 y) | Dietary interventions of varying macronutrient content | Low carbohydrate dietary vs. low fat dietary; Increased protein dietary vs. standard protein dietary; increased fat dietary vs. standard fat dietary | BMI, BMI Z-score |

| van Hoek et al., 201433 | April 15, 2012 | Overweight/obese (3–8 y) | Multicomponent treatment program, including dietary and physical activity education and behavioral therapy or treatment programs with combined dietary and physical activity education only | Some studies with control groups (no intervention) and others without control groups | BMI Z-score |

| Kelishadi et al., 201416 | 2000 to 2012 | Overweight/obese (2–18 y) | Community, family, school, and clinic interventions or a combination of them | No intervention | Weight, BMI, BMI Z-score |

| Liao et al., 201438 | July 2012 | Eutrophic, overweight or obese (≤18 y) | Reduce sedentary behavior (reduce TV/DVD/VCR, playing sedentary video/computer games, and sitting time in general) and/or increase physical activity and/or improving dietary habits | Control: some non-obesity prevention-related information; usual-programming; assessment-only | BMI |

| Martin et al., 201439 | May 2013 | Overweight/obese (3–18 y) | Lifestyle interventions | Standard care, waiting list control, no treatment or attention control | School achievement,BMI, BMI Z-scores, BMI-SDs, and measures of body fatness by DXA and BIA |

| Ruotsalainen et al., 201532 | Jan 1950 to Aug 2013 | Overweight/obesity (≤ 18 y) | Physical activity or exercise along with counseling or dietary practices | Control with standard care - no treatment related to physical activity | Physical activity level, BMI, or psychological symptoms |

| Hung et al., 201519 | NA | Children and adolescents (6–18 y)a | School-based childhood obesity prevention programs (nutrition component and/or physical activity component and/or parental involvement and/or specialist involvement) | NA | BMI and skinfold thickness |

| Foster et al., 201515 | July 1948 to July 2014 | Overweight/obese (0-6y) | Dietary advice, physical activities, behavioral management, and a motivational interview | Educational sessions | BMI, BMI percentile, or some iteration of percentage, overweight, or obese using height, weight, and waist circumference |

| Ling et al., 201617 | 1966 to Feb 2015 | Preschool children (2–5 y)a | Lifestyle intervention (any intervention that aimed to improve behaviors, including screen time, sedentary activity, physical activity, dietary, and/or sleep) | 30-min structured physical activity per day; usual care; wait-list | BMI, waist circumference, skinfold, body fat |

| Colquitt et al., 201627 | Mar 2015 | Overweight/obesity (0–6 y) | Dietary, physical activity, and behavioral interventions | No intervention or usual care | BMI, BMI Z-score |

| Murray et al., 201735 | Dec 2014 | Overweight/obese (10–19 y) | Multicomponent weight management interventions (behavioral, dietary, and physical activity components) | No treatment control | Self esteem and BMI Z-score |

| Kim et al., 201725 | April 2015 | Children and adolescents (6–18 y) | Sport-based intervention | Control | Weight |

BMI, body mass index; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis.

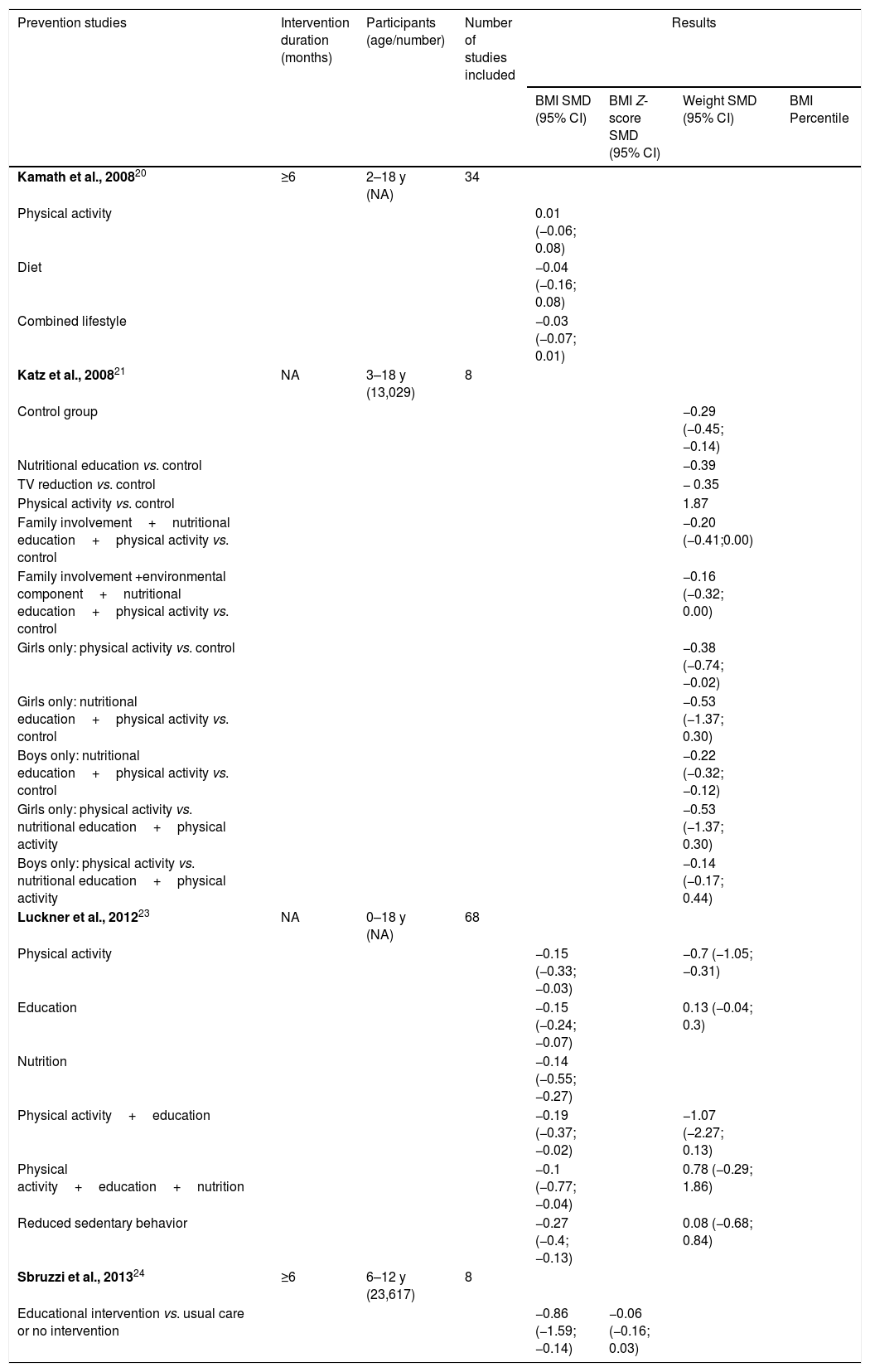

Results of reviews on prevention of obesity (standardized mean difference).

| Prevention studies | Intervention duration (months) | Participants (age/number) | Number of studies included | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI SMD (95% CI) | BMI Z-score SMD (95% CI) | Weight SMD (95% CI) | BMI Percentile | ||||

| Kamath et al., 200820 | ≥6 | 2–18 y (NA) | 34 | ||||

| Physical activity | 0.01 (−0.06; 0.08) | ||||||

| Diet | −0.04 (−0.16; 0.08) | ||||||

| Combined lifestyle | −0.03 (−0.07; 0.01) | ||||||

| Katz et al., 200821 | NA | 3–18 y (13,029) | 8 | ||||

| Control group | −0.29 (−0.45; −0.14) | ||||||

| Nutritional education vs. control | −0.39 | ||||||

| TV reduction vs. control | − 0.35 | ||||||

| Physical activity vs. control | 1.87 | ||||||

| Family involvement+nutritional education+physical activity vs. control | −0.20 (−0.41;0.00) | ||||||

| Family involvement +environmental component+nutritional education+physical activity vs. control | −0.16 (−0.32; 0.00) | ||||||

| Girls only: physical activity vs. control | −0.38 (−0.74; −0.02) | ||||||

| Girls only: nutritional education+physical activity vs. control | −0.53 (−1.37; 0.30) | ||||||

| Boys only: nutritional education+physical activity vs. control | −0.22 (−0.32; −0.12) | ||||||

| Girls only: physical activity vs. nutritional education+physical activity | −0.53 (−1.37; 0.30) | ||||||

| Boys only: physical activity vs. nutritional education+physical activity | −0.14 (−0.17; 0.44) | ||||||

| Luckner et al., 201223 | NA | 0–18 y (NA) | 68 | ||||

| Physical activity | −0.15 (−0.33; −0.03) | −0.7 (−1.05; −0.31) | |||||

| Education | −0.15 (−0.24; −0.07) | 0.13 (−0.04; 0.3) | |||||

| Nutrition | −0.14 (−0.55; −0.27) | ||||||

| Physical activity+education | −0.19 (−0.37; −0.02) | −1.07 (−2.27; 0.13) | |||||

| Physical activity+education+nutrition | −0.1 (−0.77; −0.04) | 0.78 (−0.29; 1.86) | |||||

| Reduced sedentary behavior | −0.27 (−0.4; −0.13) | 0.08 (−0.68; 0.84) | |||||

| Sbruzzi et al., 201324 | ≥6 | 6–12 y (23,617) | 8 | ||||

| Educational intervention vs. usual care or no intervention | −0.86 (−1.59; −0.14) | −0.06 (−0.16; 0.03) | |||||

Data are expressed as standardized mean difference.

NA, not available.

Kamath et al.20: Combined lifestyle interventions=interventions that include dietary changes and physical activity interventions.

Luckner et al.23: Physical activity=regular exercise; Education=information or teaching on either general healthy behavior or specifically related to nutrition, physical activity or sedentary behavior; Nutrition=intervention consisted of a change in at least one major daily meal; Reduced sedentary behavior=aimed at reducing TV viewing (TV) regardless of other components involved.

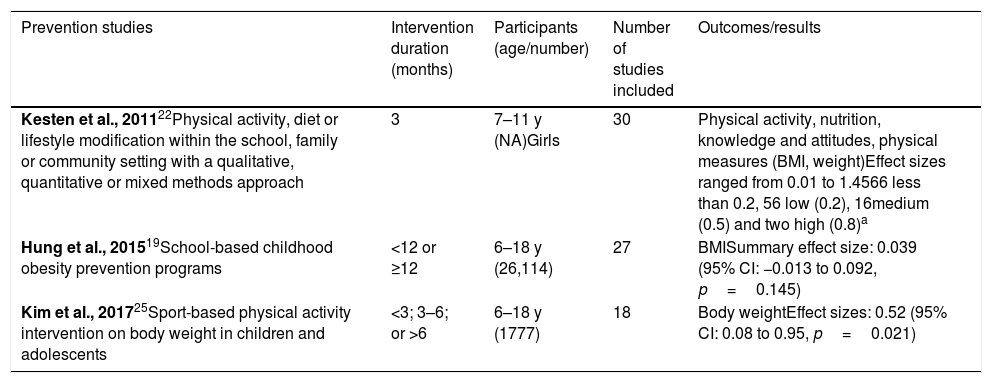

Results of reviews on prevention of obesity (effect size).

| Prevention studies | Intervention duration (months) | Participants (age/number) | Number of studies included | Outcomes/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kesten et al., 201122Physical activity, diet or lifestyle modification within the school, family or community setting with a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach | 3 | 7–11 y (NA)Girls | 30 | Physical activity, nutrition, knowledge and attitudes, physical measures (BMI, weight)Effect sizes ranged from 0.01 to 1.4566 less than 0.2, 56 low (0.2), 16medium (0.5) and two high (0.8)a |

| Hung et al., 201519School-based childhood obesity prevention programs | <12 or ≥12 | 6–18 y (26,114) | 27 | BMISummary effect size: 0.039 (95% CI: −0.013 to 0.092, p=0.145) |

| Kim et al., 201725Sport-based physical activity intervention on body weight in children and adolescents | <3; 3–6; or >6 | 6–18 y (1777) | 18 | Body weightEffect sizes: 0.52 (95% CI: 0.08 to 0.95, p=0.021) |

Data is expressed as effect size.

NA, not available; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index.

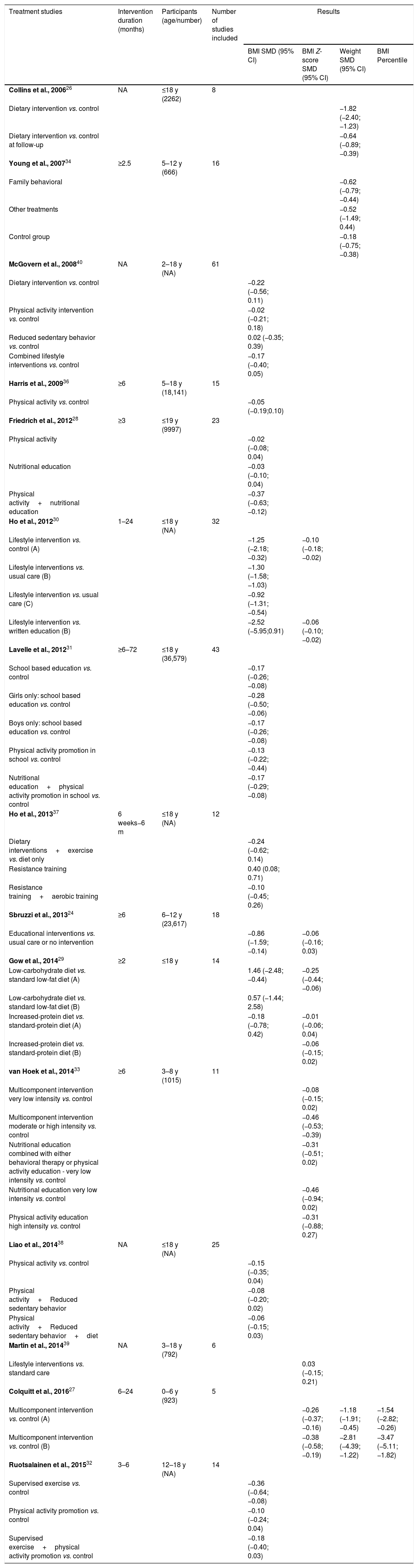

Results of reviews on treatment of obesity (standardized mean difference).

| Treatment studies | Intervention duration (months) | Participants (age/number) | Number of studies included | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI SMD (95% CI) | BMI Z-score SMD (95% CI) | Weight SMD (95% CI) | BMI Percentile | ||||

| Collins et al., 200626 | NA | ≤18 y (2262) | 8 | ||||

| Dietary intervention vs. control | −1.82 (−2.40; −1.23) | ||||||

| Dietary intervention vs. control at follow-up | −0.64 (−0.89; −0.39) | ||||||

| Young et al., 200734 | ≥2.5 | 5–12 y (666) | 16 | ||||

| Family behavioral | −0.62 (−0.79; −0.44) | ||||||

| Other treatments | −0.52 (−1.49; 0.44) | ||||||

| Control group | −0.18 (−0.75; −0.38) | ||||||

| McGovern et al., 200840 | NA | 2–18 y (NA) | 61 | ||||

| Dietary intervention vs. control | −0.22 (−0.56; 0.11) | ||||||

| Physical activity intervention vs. control | −0.02 (−0.21; 0.18) | ||||||

| Reduced sedentary behavior vs. control | 0.02 (−0.35; 0.39) | ||||||

| Combined lifestyle interventions vs. control | −0.17 (−0.40; 0.05) | ||||||

| Harris et al., 200936 | ≥6 | 5–18 y (18,141) | 15 | ||||

| Physical activity vs. control | −0.05 (−0.19;0.10) | ||||||

| Friedrich et al., 201228 | ≥3 | ≤19 y (9997) | 23 | ||||

| Physical activity | −0.02 (−0.08; 0.04) | ||||||

| Nutritional education | −0.03 (−0.10; 0.04) | ||||||

| Physical activity+nutritional education | −0.37 (−0.63; −0.12) | ||||||

| Ho et al., 201230 | 1–24 | ≤18 y (NA) | 32 | ||||

| Lifestyle intervention vs. control (A) | −1.25 (−2.18; −0.32) | −0.10 (−0.18; −0.02) | |||||

| Lifestyle interventions vs. usual care (B) | −1.30 (−1.58; −1.03) | ||||||

| Lifestyle intervention vs. usual care (C) | −0.92 (−1.31; −0.54) | ||||||

| Lifestyle intervention vs. written education (B) | −2.52 (−5.95;0.91) | −0.06 (−0.10; −0.02) | |||||

| Lavelle et al., 201231 | ≥6–72 | ≤18 y (36,579) | 43 | ||||

| School based education vs. control | −0.17 (−0.26; −0.08) | ||||||

| Girls only: school based education vs. control | −0.28 (−0.50; −0.06) | ||||||

| Boys only: school based education vs. control | −0.17 (−0.26; −0.08) | ||||||

| Physical activity promotion in school vs. control | −0.13 (−0.22; −0.44) | ||||||

| Nutritional education+physical activity promotion in school vs. control | −0.17 (−0.29; −0.08) | ||||||

| Ho et al., 201337 | 6 weeks−6 m | ≤18 y (NA) | 12 | ||||

| Dietary interventions+exercise vs. diet only | −0.24 (−0.62; 0.14) | ||||||

| Resistance training | 0.40 (0.08; 0.71) | ||||||

| Resistance training+aerobic training | −0.10 (−0.45; 0.26) | ||||||

| Sbruzzi et al., 201324 | ≥6 | 6–12 y (23,617) | 18 | ||||

| Educational interventions vs. usual care or no intervention | −0.86 (−1.59; −0.14) | −0.06 (−0.16; 0.03) | |||||

| Gow et al., 201429 | ≥2 | ≤18 y | 14 | ||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet vs. standard low-fat diet (A) | 1.46 (−2.48; −0.44) | −0.25 (−0.44; −0.06) | |||||

| Low-carbohydrate diet vs. standard low-fat diet (B) | 0.57 (−1.44; 2.58) | ||||||

| Increased-protein diet vs. standard-protein diet (A) | −0.18 (−0.78; 0.42) | −0.01 (−0.06; 0.04) | |||||

| Increased-protein diet vs. standard-protein diet (B) | −0.06 (−0.15; 0.02) | ||||||

| van Hoek et al., 201433 | ≥6 | 3–8 y (1015) | 11 | ||||

| Multicomponent intervention very low intensity vs. control | −0.08 (−0.15; 0.02) | ||||||

| Multicomponent intervention moderate or high intensity vs. control | −0.46 (−0.53; −0.39) | ||||||

| Nutritional education combined with either behavioral therapy or physical activity education - very low intensity vs. control | −0.31 (−0.51; 0.02) | ||||||

| Nutritional education very low intensity vs. control | −0.46 (−0.94; 0.02) | ||||||

| Physical activity education high intensity vs. control | −0.31 (−0.88; 0.27) | ||||||

| Liao et al., 201438 | NA | ≤18 y (NA) | 25 | ||||

| Physical activity vs. control | −0.15 (−0.35; 0.04) | ||||||

| Physical activity+Reduced sedentary behavior | −0.08 (−0.20; 0.02) | ||||||

| Physical activity+Reduced sedentary behavior+diet | −0.06 (−0.15; 0.03) | ||||||

| Martin et al., 201439 | NA | 3–18 y (792) | 6 | ||||

| Lifestyle interventions vs. standard care | 0.03 (−0.15; 0.21) | ||||||

| Colquitt et al., 201627 | 6–24 | 0–6 y (923) | 5 | ||||

| Multicomponent intervention vs. control (A) | −0.26 (−0.37; −0.16) | −1.18 (−1.91; −0.45) | −1.54 (−2.82; −0.26) | ||||

| Multicomponent intervention vs. control (B) | −0.38 (−0.58; −0.19) | −2.81 (−4.39; −1.22) | −3.47 (−5.11; −1.82) | ||||

| Ruotsalainen et al., 201532 | 3–6 | 12–18 y (NA) | 14 | ||||

| Supervised exercise vs. control | −0.36 (−0.64; −0.08) | ||||||

| Physical activity promotion vs. control | −0.10 (−0.24; 0.04) | ||||||

| Supervised exercise+physical activity promotion vs. control | −0.18 (−0.40; 0.03) | ||||||

NA, not available.

Collins et al.26: control group received usual care or no intervention.

Young et al.34: Family behavioral=use of at least one named behavioral or cognitive-behavioral technique to encourage children to pursue and maintain healthy physical and/or eating habits; Other treatments=behavioral treatments analogous to the family-behavioral groups without the direct involvement of the parents, Control group=not defined.

McGovern et al.40: Dietary interventions=reduced-glycemic-load diet, protein-sparing modified diet, low-carbohydrate diet, high-protein diet, and hypocaloric diet; combination lifestyle interventions=physical activity and dietary modification.

Harris et al.36: Physical activity: intervention took place during regular class time; Control group=continued with the existing physical education curriculum of school.

Ho et al.30: A=at latest point of follow-up, B=at the end of active treatment. C=at follow up. Lifestyle intervention=program incorporating a nutrition or dietary component; control=no treatment; usual care=minimal advice; written education=written diet and physical activity education materials.

Lavelle et al.31: School based education=physical activity promotion and/or sedentary behavior reduction and/or nutritional education.

Ho et al.37: Dietary interventions=calorie restriction approach, with energy levels ranging from 900 to 1800kcal/d and with varied macronutrient combinations. Others either used the Traffic Light Diet, aimed at limiting added sugar consumption and increasing dietary fiber intake or provided general dietary advice.

Sbruzzi et al.24: Educational intervention=school-based program defined as an intervention strategy performed in the school and/or family based program.

Gow et al.29: A=end of intervention; B=2-year follow up.

Van Hoek et al.33: multicomponent intervention=dietary, physical education and behavioral therapy; Intensity of treatment (duration over the course of the intervention period) was categorized as very low (<10hours), low (10–25hours), moderate (26–75hours), or high (>75hours).

Liao et al.38: Sedentary behaviors=watching TV/DVD/VCR, playing sedentary video/computer games and sitting time in general.

Martin et al.39: lifestyle intervention (physical activity promotion, sedentary behavior reduction, nutritional education, psychological interventions).

Colquitt et al.27: multicomponent intervention (nutritional, physical activity, and behavioral interventions); A=end of intervention (6–12 months); B=12–18 months follow-up (6–8 months post intervention);

Ruotsalainen et al.32: control=standard care.

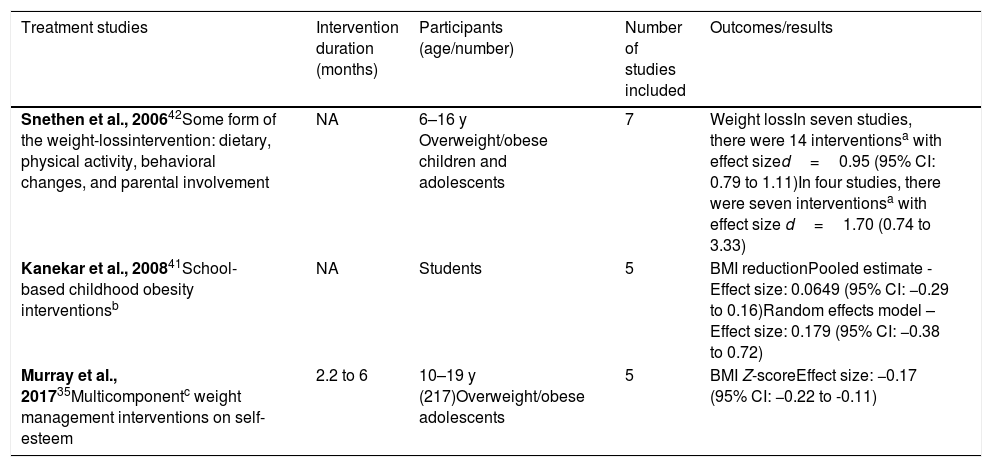

Results of reviews on treatment of obesity (effect size).

| Treatment studies | Intervention duration (months) | Participants (age/number) | Number of studies included | Outcomes/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snethen et al., 200642Some form of the weight-lossintervention: dietary, physical activity, behavioral changes, and parental involvement | NA | 6–16 y Overweight/obese children and adolescents | 7 | Weight lossIn seven studies, there were 14 interventionsa with effect sized=0.95 (95% CI: 0.79 to 1.11)In four studies, there were seven interventionsa with effect size d=1.70 (0.74 to 3.33) |

| Kanekar et al., 200841School-based childhood obesity interventionsb | NA | Students | 5 | BMI reductionPooled estimate - Effect size: 0.0649 (95% CI: −0.29 to 0.16)Random effects model – Effect size: 0.179 (95% CI: −0.38 to 0.72) |

| Murray et al., 201735Multicomponentc weight management interventions on self-esteem | 2.2 to 6 | 10–19 y (217)Overweight/obese adolescents | 5 | BMI Z-scoreEffect size: −0.17 (95% CI: −0.22 to -0.11) |

NA, not available; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

From the 24 reviews, six of them were on obesity prevention, 17 were on obesity treatment, and one review included mixed interventions for prevention and treatment of obesity (Table 1). Eleven (46%) of the included studies had been published in the last five years. The majority of reviews included children and adolescents until the age of 18; five (21%) considered only children. Intervention type and settings were highly diverse among reviews, and length of intervention varied from 2.5 to 72 months. The outcomes described were weight, BMI, BMI Z-score, fat content, fat distribution, anthropometric measures (waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, triceps skin-fold thickness, and subscapular skin-fold thickness), dietary behavior, sedentary behavior, physical activity behavior, and cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, lipids, and glucose).

Obesity preventionSeven systematic reviews with meta-analysis addressed the interventions for childhood and adolescent obesity prevention.19–25 The main results are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The number of studies included in each review ranged from eight to 68. Two of these reviews were based on educational programs,19,24 one in sport-based physical activity intervention,25 and the other four offered mixed interventions for prevention, including nutrition changes, physical activity stimulation, and sedentary behavior reduction.20–23

Three reviews addressing lifestyle behavior changes (nutrition, physical activity, or both),20 educational interventions,24 and school-based childhood obesity prevention programs19 did not show any significant effect on BMI when compared with control. However, three other reviews21–23 showed that these interventions produced significant but modest short-term weight reduction: two showed these results for nutritional education, TV watching reduction, and physical activity (alone or in combination with a parent or family involvement),21,23 and one showed positive results for physical activity, diet, or lifestyle modification within the school, family, or community setting.22

Obesity treatmentEighteen systematic reviews with meta-analysis addressed the interventions for childhood and adolescent obesity treatment. The main results are presented in Tables 4 and 5. The number of studies included in each review ranged between five and 61. Of these reviews, ten26–35 have shown that interventions such as diet, family behavior, physical activity promotion, supervised exercise, lifestyle or multicomponent intervention, school-based education, and low-carbohydrate diet26–34 were associated with reduction in the main outcomes. However, 11 studies24,28,29,32,33,36–40 did not observe an association between the interventions (dietary intervention, physical activity promotion, resistance training, reduced sedentary behavior, lifestyle or educational intervention, nutritional education, and increased-protein diet) and reduction in the main outcomes.

The interventions were based on nutritional changes, physical activity stimulation, sedentary behavior reduction, and educational interventions, alone or in combination, as follows.

Reviews that included mixed interventions for obesity treatmentIn their study, van Hoek et al.33 showed significant improvement in BMI Z-score with multi-component intervention associated with decreased cardiovascular risk factors and insulin resistance in children. In turn, Liao et al.38 failed to demonstrate that multi-component interventions were more effective in BMI reduction than sedentary behavior-only interventions.

Friedrich et al.28 showed that only the interventions that combined physical activity and nutritional education had positive effects on BMI reduction when compared with interventions applied separately.

Kanekar et al.41 analyzed only studies performed in the United States and in the United Kingdom, and showed that school-based interventions were not associated with BMI changes.

Snethen et al.42 examined the effectiveness of 14 different combination of interventions (dietary, physical activity, behavioral change, and parental involvement) and showed that the effect size for weight loss was small. However, longer intervention programs produced better results.

Reviews that included dietary interventions for obesity treatmentTwo meta-analyses26,40 assessed only the effectiveness of dietary interventions on the treatment of obese children and adolescents and demonstrated some effect on weight loss, although details on dietary intervention or participants’ food intake were rarely described in studies; therefore, it was not possible to evaluate which particular dietary intervention was the most effective.

One study29 examined the effectiveness of diets varying in macronutrient distribution as part of a weight management intervention in overweight or obese children and adolescents. An improvement on weight status was achieved regardless of the macronutrient distribution of a reduced-energy diet.

In studies measuring cardio-metabolic outcomes, improvements in blood lipids, blood glucose, insulin resistance, and blood pressure were reported.29,30

Reviews that included physical activity interventions for obesity treatmentOnly one meta-analysis assessed the impact of physical activity alone on obesity treatment36 and failed to demonstrate any effect of exercise alone on body weight, BMI or central obesity. Only a moderate decrease on fat percentage was observed with physical activity intervention.

Reviews that included educational interventions for obesity treatmentSbruzzi et al.24 showed that educational interventions for at least six months were associated with a significant reduction in waist circumference, BMI, and diastolic blood pressure.

DiscussionThe purpose of this review was to help readers of systematic reviews to critically appraise the available scientific information on prevention and non-pharmacological treatment of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence. This analysis showed that 19 studies (80%) were of low or very low quality according to the AMSTAR 2 criteria, i.e., the studies have a low degree of confidence in the results. Nevertheless, almost all authors have drawn attention to the heterogeneity of the included studies in their systematic reviews and to the low quality of many primary studies, which compromise their translation into definitive recommendations in any context.

The prevention studies demonstrated small and short-term effects or no effect on body weight.19–23 Parental involvement and reducing television time were the interventions associated with the greatest benefits.16,19,22–24,34,38

Considering the studies focused in treating obesity in childhood and adolescence, the vast majority of them showed no significant effects on weight reduction and maintenance with numerous well-known interventions. Some positive results were reported in short-term and multi-component interventions, but no definitive recommendation can be drawn on the intervention type or duration needed to achieve long-term success. These results are in line with what is already known from the nonpharmacological treatment of obesity in adults.

Despite the small improvement on body weight and adiposity in children observed from increase in physical activity in the reviewed studies,20,21,28,32,33,36–38,40 structured physical activity programs may lead to other benefits, such as improved coordination skills, skeletal health, flexibility, and aerobic capacity; greater self-confidence; team participation; and social inclusion. So far, no definitive conclusion can be made on the efficacy of physical activity to prevent or reduce obesity in children and adolescents, but the importance of developing actions and programs to promote active lifestyles should be targeted. Moreover, the practice of regular physical activity, starting early in childhood or adolescence, may prevent sedentary lifestyles in adult life.43

Studies evaluating different dietary approaches failed to recognize benefits of a particular type of diet or macronutrients composition,20,26,27,29,30,37,38,40 perhaps because details on dietary intervention or participant's food intake were rarely described in studies and there was a high heterogeneity of designs and outcome measures.

The current analysis showed many limitations in published reviews so far, such as the heterogeneity of primary studies including the intervention length, parental involvement or not, nutrition targets, physical activity programs, and educational targets, which also makes it hard for a single meta-analysis study to conclude the best intervention.

One challenging aspect for healthy weight promotion strategies is adherence outside schools. Healthy eating is negatively impacted by the food industry through advertisements and other marketing strategies to stimulate consumption of calorie-dense foods and beverages.44 Technological devices such as videogames and computers attract children to a lifestyle of little physical activity and increased calorie consumption.45 Interventions have better results when the strategy includes a family component, because children are strongly influenced by their parents’ habits.46 Therefore, recommendations introduced in schools should be followed at home through the positive example of parents for their children, through healthy nutrition and the regular practice of physical activity.47

Several factors contribute to obesity, including genetic, environmental, metabolic, biochemical, psychological, and physiological.23 These complex causal links make it unlikely that any single intervention will be successful for obesity prevention or treatment. Despite the considerable ongoing academic research evaluating preventive and therapeutic approaches to childhood obesity, there is a lack of strong evidence at comprehensive strategies to reverse the alarming obesity trends.

Healthcare professionals, politicians, and several stakeholders will likely need to combine different approaches targeting schools, communities, clinics, worksites, households, urban design, food marketing regulation, and taxation to effectively control the obesity epidemic. There is a growing consensus that large changes in population levels of physical activity and eating behaviors would be needed to control the obesity epidemics, requiring major modifications in built and food environments and policies.48

Environmental changes or community-wide multilevel interventions (built environment attributes such as, recreation and transportation purpose) had recently been shown to provide positive effects on physical activity and obesity in children.49,50 Moreover, racial/ethnic minorities and low-income communities are disadvantaged in access to recreation facilities, positive esthetics, and protection from traffic.48 Engaging policy makers in the process of modifying the food environment and in evaluating the costs and benefits of programs and policies designed for these modifications prior to implementation is also very important.51 Furthermore, regulatory actions in markets should be considered in this context. The authors believe that only when an array of strategies has been aligned with global cooperation, can we reasonably hope to see significant improvements in the obesity scenario.

ConclusionThe available scientific evidence on the effects of clinical and behavioral interventions to reduce obesity is of low quality, very heterogeneous, and not conclusive. Based on existing evidence, any single component intervention for obesity prevention or treatment of children and adolescents is likely to produce minor and non-durable effects on body weight, adiposity, and cardio-metabolic outcomes. The involvement of all society and government, not just healthcare professionals, is necessary to achieve better results in the prevention and treatment of this dangerous epidemic of childhood obesity.

FundingLB, GAA, and LAB received research grants from the Institute for Health Technology Assessment (Instituto de Avaliação de Tecnologia em Saúde [IATS]).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Bahia L, Schaan CW, Sparrenberger K, Abreu GA, Barufaldi LA, Coutinho W, et al. Overview of meta-analysis on prevention and treatment of childhood obesity. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:385–400.