Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) is an underdiagnosed autosomal recessive disease with onset between the first years of life and adulthood. Early diagnosis is crucial for effective therapy and long-term survival. The objective of this article is to recognize warning signs among the clinical and laboratory characteristics of LAL-D in pediatric patients through a scope review.

SourcesElectronic searches in the Embase, PubMed, Livivo, LILACS, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, Open Gray, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses databases. The dataset included observational studies with clinical and laboratory characteristics of infants, children and adolescents diagnosed with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency by enzyme activity testing or analysis of mutations in the lysosomal acid lipase gene (LIPA). The reference selection process was performed in two stages. The references were selected by two authors, and the data were extracted in June 2020.

Summary of the findingsThe initial search returned 1593 studies, and the final selection included 108 studies from 30 countries encompassing 206 patients, including individuals with Wolman disease and cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD). The most prevalent manifestations in both spectra of the disease were hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anemia, dyslipidemia, and elevated transaminases.

ConclusionsVomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, and splenomegaly may be correlated, and may serve as a starting point for investigating LAL-D. Familial lymphohistiocytosis should be part of the differential diagnosis with LAL-D, and all patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be submitted to intestinal biopsy.

Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the lysosomal acid lipase gene (LIPA), located on chromosome 10q23.2-q23.3 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database # 27800). Approximately 120 disease-associated mutations have been reported.1,2 LAL-D is a heterogeneous disease, but the onset for most patients occurs in childhood, with progressive liver failure and cardiovascular events in adolescence and adulthood.

The reduced activity of lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) results in progressive storage of cholesteryl esters and triglycerides in hepatocytes, adrenal glands, intestines, and macrophage-monocyte system cells throughout the body.1 Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency induces two spectra of clinical severity: infantile LAL-D, referred to as Wolman disease, and a less aggressive, which has historically been known as cholesteryl ester storage disease (CESD).3 Wolman disease is a rare, fulminant subtype with less than 1-2% of the normal activity of lysosomal acid lipase,4 presenting clinically as increased triglycerides storage, growth failure and liver disease, with death occurring in the first 6 months of life.3,5,6

CESD has a variable and milder clinical presentation, characterized by liver fibrosis, high cholesterol and accelerated atherosclerosis, and can be diagnosed at any time between a few years of age and adulthood.1 Hepatomegaly, abnormal liver function tests, altered lipid profile, gastrointestinal disorders, multisystem failure, and death in childhood and adolescence may occur if the disease is left untreated.7,8

Several case reports and review studies have been published since 1960, leading to an improvement in our knowledge of genetics, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation of LAL-D.9 The relatively low number of cases diagnosed with LAL-D in comparison to its genetic prevalence is likely explained by a low degree of suspicion for the diagnosis. For this reason, raising pediatrician awareness about this condition is an essential step for identifying individuals with LAL-D, as there are means for diagnosis available after the disease is suspected. Early diagnosis of LAL-D is essential for effective therapy and long-term survival,7,9 and the development of enzyme replacement therapy with sebelipase alfa as a possible therapy has made the correct diagnosis of the condition even more crucial.10,11

The main objective of this article is to recognize the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with lysosome acid lipase deficiency, considering those with onset and diagnosis of the disease in childhood and adolescence. The guiding question of the research was: “What are the signs and symptoms that may alert pediatricians to an early diagnosis of LAL-D?”.

Material and methodsThe research protocol was organized according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement and registered in the Open Science Framework.12,13 Specific search strategies were developed for each database: Embase, LILACS, Livivo, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. Gray literature research was addressed using Google Scholar, OpenGrey and Proquest Dissertations and Theses (Supplementary Material Table S1). The final search date for all database searches was June 2020.

This review included descriptive observational studies (case reports and case series) with clinical and laboratory characteristics of infants, children and adolescents diagnosed with LAL-D by enzyme activity testing or analysis of mutations in the LIPA gene. The exclusion criteria used were: 1) Patients over 18 years old; 2) Studies that did not perform laboratory exams to confirm the diagnosis; 3) Studies that did not report patients' clinical and laboratory characteristics; 4) Secondary studies (article reviews, letters to the editor, books and book chapters); 5) Studies not published in the Latin-Roman alphabet; 6) Studies for which the full text was unavailable; 7) Studies not including patients with lysosomal acid lipase deficiency; 8) Studies dealing with a previously published case.

The references cited in the selected articles were also checked in case they might have been missed during the initial searches in the electronic databases. The authors also contacted authors of articles on the disease to ask for suggestions for additional papers. All references were managed using the Endnote X8 reference manager software® (Clarivate Analytics), and duplicated occurrences were removed.

The reference selection process was performed in two stages. In stage 1, two reviewers (CRW and ACS) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all references identified from the electronic databases. A third author (MMSP) was involved, when asked, to make a final decision. Any studies that did not appear to meet the inclusion criteria were discarded. In stage 2, the same selection criteria were applied to the complete articles to confirm their eligibility. The same two reviewers (CRW and ACS) participated independently in stage 2. The list of references of the included articles was reviewed by one examiner (CRW). The selected articles were read by both examiners (CRW and ACS). Disagreements in any of the stages were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement between the three reviewers (CRW, ACS, MMSP). The final decision to include a publication was always made based on its full text.

The following information was recorded for all studies included in the final dataset: year of publication, author, country, disease spectrum, sex, inbreeding, symptoms, characteristics, and comorbidities (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, growth failure, adrenal calcifications, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, jaundice, esophageal varices, umbilical hernia, inguinal hernia, incidental intraoperative findings, portal hypertension, liver cirrhosis, neurological symptoms, systemic arterial hypertension, pulmonary symptoms, stroke, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis). Regarding laboratory tests, the following information was recorded: complete blood count with platelets, concentrations of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, total bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), percentage of LAL activity and LIPA mutation. Tissue tests and pathologies (e.g. liver, bone marrow, intestinal) were also recorded. A symptom was considered present if the patient presented it at any time during the course of the disease, considering symptom reports and laboratory tests. If more than one value for a laboratory test was mentioned for a specific case, the authors used the value corresponding to the time of diagnosis.

Authors of potentially eligible full articles were contacted to provide further details about their studies when there were questions. One author (CRW) collected the necessary information from the selected articles. Another author (ACS) verified all the information collected. Once again, disagreements at any stage were resolved by discussion and mutual agreement between the three reviewers (CRW, ACS, MMSP). Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica® 5.0 software (StatSoft, Brazil). Descriptive statistics and multiple correspondence analyses were computed considering the disease spectrum and groups of variables.

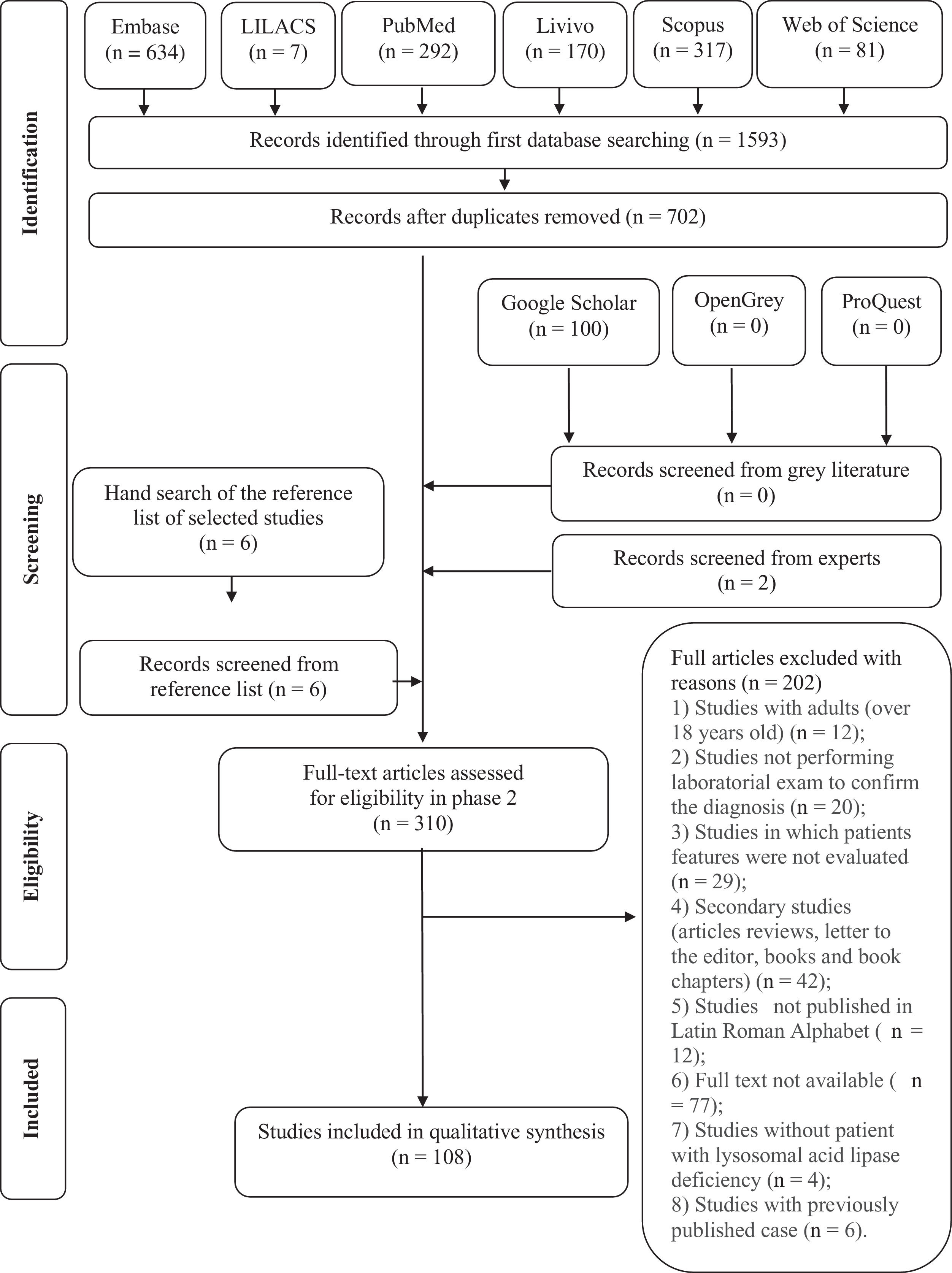

ResultsDuring the initial stage, 1,593 references were identified in the six electronic databases used. Only 702 articles remained after removing duplicated entries. A comprehensive assessment of the abstracts resulted in the retention of 302 articles after stage 1. An additional 100 references were identified on Google Scholar; however, none of those met the inclusion criteria for stage 1. Six additional studies were identified after the manual search on the reference lists of those articles. Two further studies were added by an expert on the subject. Therefore, the final count at the end of this stage was 310 articles. After a full-text review, 202 studies were excluded. The reasons for exclusion can be found in Table S2 in the supplementary material. At the end of the selection process, only 108 articles were retained.14-119 A flowchart of the study identification, inclusion and exclusion process is shown in Fig. 1. The PRISMA-ScR checklist can be found in the supplementary material.

The pediatric studies included were published between 1970 and 2020 and conducted in thirty different countries. Most were published in Germany,50,64,74,80,95,101 Italy 25,48,73,77,89-92,96,109 and the United States.18-20,29,37,42-45,49,52,55,56,61,67,72,78,83,84,108,111,114

Most patients were from Italy,25,48,73,77,89-92,96,109 Poland 75,76,113 and the United States.18-20,29,37,42-45,49,52,55,56,61,67,72,78,83,84,108,111,114 The patients in selected articles were grouped into two categories: infantile-onset LAL-D, or CESD. A total of 206 patients were included, 73 with infantile LAL-D presentation and 133 with CESD. Molecular data were available for 109 patients, including 57 different mutations. Approximately 50% 55 of the reported cases with molecular data had the exon eight splice junction mutation (E8SJM; c.894G> A), and 19.2% were homozygous for this mutation. A summary of individual patients, including mutations associated with LAL-D and the characteristics of the studies and patients, can be found in Table S3 in the supplementary material.

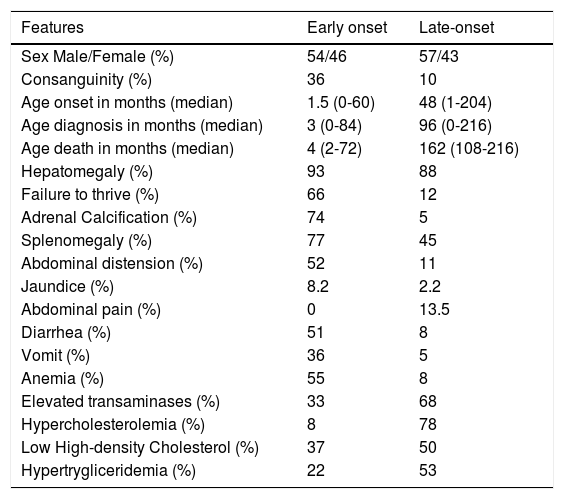

The median age at which the first symptoms were reported was 1.5 months for early-onset patients and 48 months for CESD. The median age at diagnosis was three months and 96 months for infantile-onset LAL-D and CESD, respectively. The median age of death was four months for Wolman disease and 162 months for CESD. Inbreeding was reported in 19% of the total sample (39 cases) and was more prevalent in cases with Wolman disease. Diarrhea, vomiting, growth retardation, and adrenal calcification were frequent in the infantile LAL-D presentation, but also present in CESD, albeit less frequently. Abdominal pain was present in 14% of the cases reported in the total CESD sample. In seven patients, the investigation of LAL-D started after incidental findings during surgery (aganglionosis, appendicitis, orthopedic surgery, intestinal intussusception). The clinical, radiographic and biochemical characteristics reported in patients with lysosomal lipase acid deficiency are described in Table 1.

Reported clinical, radiographic, biochemical features in lysosomal lipase acid deficiency patients.

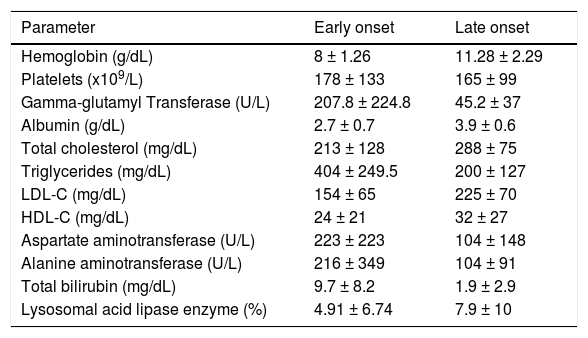

Hepatomegaly was an important sign in the physical examination, present in 93% of the early-onset patients and 88% of the patients with CESD. Splenomegaly was also frequent, occurring in 77% of the Wolman disease patients and 45% of the patients with CESD. Umbilical and inguinal hernia was present in nine patients. All patients with Wolman disease whose blood count was described had anemia. The case reports for these patients had no history of bleeding. Three cases had a history of intestinal malabsorption and diarrhea, and 59.2% had fatty infiltration of the bone marrow. Thrombocytopenia was present in 26% of the patients with infantile-onset LAL-D. Elevated ferritin (> 500 ng/mL) was reported in 12 patients with Wolman disease. The means and standard deviations of the biochemical parameters are reported in Table 2.

Reported biochemical features in lysosomal acid lipase deficiency patients.

Values are mean ± Standard Deviation.

g, gram; ng, nanogram; mg, milligram; dL, deciliter; ml, milliliter; L, liter; U, unit; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Descriptions of upper digestive endoscopy procedures were available in the case reports of 15 patients. Portal hypertension was evidenced by esophageal varices in five patients and found along with hypertensive gastropathy in two patients. One patient was described as having a pale yellowish duodenal mucosa. For duodenal biopsies, nine patients had reports of intestinal anatomopathological findings, all of which had the presence of histiocytes with lipid vacuoles.

Pathological studies were performed on the liver, bone marrow and duodenum during the investigation of patients while alive and in autopsies. Liver biopsy was performed in 120 of all patients studied, showing degrees of liver pathology varying from early stages with hepatocyte swelling to fibrosis and cirrhosis. Steatosis was common, being reported in 89 patients. Microvesicular steatosis was found in 31 patients with CESD and 16 of the early-onset patients. Kupffer cell hypertrophy was found on the biopsies of 47 patients, 25 from the late-onset group and 22 from the early-onset group. The presence of fibrosis in biopsies was described as 52%, cirrhosis in 13%, and cholesterol crystals in 32% of the patients who underwent liver biopsy. Bone marrow biopsy was performed in 40 patients, the main finding being lipid-laden foamy histiocytes in 68% of the biopsies, including 14 patients with the early-onset form and 13 late-onset patients. Reports of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow biopsies occurred in 10 patients out of the 73 with Wolman disease, corresponding to 13.6% of the sample for this disease.

The numbers generated from simple and inertia values for all dimensions of the independent variables in the multiple correspondence analysis showed that vomiting is associated with diarrhea in both disease spectra. There was an association between jaundice and splenomegaly, especially in Wolman disease.

DiscussionLAL-D is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the LIPA gene, located on chromosome 10q23.2-q23.3. A genetic epidemiological analysis carried out by Carter et al. in adults and children found 120 different disease-causing mutations.2,9,120,121 In the present study, the authors found 57 different mutations. As described in the literature, approximately 50% of patients had the most common deleterious variant: a splice junction mutation in exon 8 (E8SJM c.894G> A), related to CESD – only one early-onset patient in this review had the E8SJM c.894G> A variant. Reported mutations related to Wolman disease were unique in 23 of the 25 patients who underwent an analysis of LIPA mutations; homozygous mutations were described in 13 patients, as shown in supplementary Table S3. Jones et al, in a study with 35 patients from 17 centers in six countries, reported 10 unique mutations in 12 patients studied.6

LAL activity is based on the measurement of LAL level in peripheral blood leukocytes, cultured fibroblasts and liver tissue using various lipase substrates not specific for LAL, thereby precluding direct comparisons of residual LAL activity between patients. Besides the analysis of mutations, the authors use the percentage of normal activity to provide an informative value.1,18 LAL activity is dramatically reduced in Wolman disease. The literature mentions activities of about 1-2% of normal controls, while in the present review the authors found a mean reported level of approximately 4.91%. Enzyme activity was described in 94 CESD patients, ranging from “undetectable”, or 0%, to 50% of the minimum normal values; the average level was 7.9 %. Due to the variability in the assays, the reported residual enzyme activity did not necessarily predict the severity of the disease.1

Analyzing the interval between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis, even when taking into account that many articles did not differentiate both dates there is clearly a period during which diagnoses are incorrect or absent. The median age of disease onset in the present study was similar to that described in the literature: one month and 60 months, respectively, for early-onset and late-onset presentations. There was a considerable gap for both disease spectra – approximately two months in Wolman disease and three years in CESD.3,6,121,122 The median age at death for Wolman disease was four months, similar to the median life expectancy reported by Jones et al.5 In seven patients (3.64%), an incidental diagnosis was made during a surgical procedure, which should serve as a warning about the current underdiagnosis and the need for attention from the pediatricians responsible for these patients' care. Although the investigation was initiated due to the macroscopic liver characteristics found during the surgery, these patients had previous laboratory and clinical anomalies prior to the surgical procedure which had not been valued by the attending physicians.2,54-56,61,65,112,114 The long gap between the first symptoms of the disease and the diagnosis is explained by a lack of awareness and knowledge about LAL-D.123

Hepatomegaly was the most common sign in infantile-onset LAL-D and CESD, and should be treated as a trigger for investigating these patients. Most patients also had splenomegaly. These characteristics were present in both disease spectra, and their prevalence was in accordance with that found in the literature.3,76,122,124,125 Adrenal calcification, growth failure, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distension, and anemia were present from the start and constantly in the early-onset form of the disease.6,7,9,25,101,125-128 Elevated serum transaminases, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL are guides for the correct diagnosis of CESD.1,3,7,8,124,125 The multiple correspondence analysis suggested that simple symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, and splenomegaly may be correlated, thus becoming a starting point for the investigation of LAL-D.

Abdominal pain is extremely common during childhood and adolescence and leads to frequent presentations to routine medical care. The present study reported 18 child and adolescent patients (14%) for whom abdominal pain was a common symptom, all with CESD. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, jaundice, and gallbladder dysfunction were concomitant abnormalities in these patients.23,34,37,45,54,59,74,76,113,129 These signs and symptoms may be "red flags" associated with lipase acid deficiency in the investigation of abdominal pain. Umbilical and inguinal hernias were found in the early-onset spectrum, occurring in 12% of the patients, similar to their prevalence in the general population.130

Hematological changes were present in the studied patients with Wolman disease, including reports of anemia (55%), thrombocytopenia (26%) and elevated ferritin (16.4%). Pediatric patients with LAL-D present a massive accumulation of triglycerides and esterified cholesterol in the tissues, especially in the intestinal villi, leading to malabsorption. Vacuolated lymphocytes in the blood smear were reported in 5.3% of the patients, and are indicative of a lysosomal storage disease. For that reason, their presence can raise suspicion of DAL-D and increase the chance of diagnosis. Foamy histiocytes in the bone marrow were found in 59.2% of the patients with anemia, contributing to ineffective hematopoiesis. Differential diagnosis of the increased number of foamy histiocytes in the bone marrow must be made with storage disorders, including Gaucher disease and Niemann-Pick disease, the clinical and laboratory characteristics of which overlap with those of LAL-D.131

Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) is a rare autosomal recessive disease that usually presents its first symptoms in the first months or years of life. The main signs and symptoms of this disease include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anemia, leukopenia or thrombocytopenia, elevated ferritin, and hypertriglyceridemia. These findings allow a differential diagnosis with inborn errors of metabolism and with lysosomal storage disease. Twelve early-onset LAL-D patients in the authors’ database, 16.4% of the total sample, had a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome in their reports. Due to the overlapping characteristics between LAL-D and FHL and the potential for incorrect diagnosis, patients with a negative FHL mutation should be tested for LAL-D.47,94,100,109,110

Biochemical liver abnormalities were present early in the course of LAL-D disease.3,6,124 ALT, AST and albumin concentrations below the normal range, elevated GGT and bilirubin levels were characteristic in the early-onset form, in agreement with a more aggressive disease spectrum, as shown in Table 2. In patients with LAL-D, there is a fibrosis-inducing insult that generates inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, and, consequently, cirrhosis during the long period before correct diagnosis and the beginning of treatment, i.e. while the causal factor of these changes is not removed.3

The LAL enzyme plays a decisive role in cholesterol metabolism. In normal patients, LDL-C is internalized through LDL receptors and incorporated into intracellular lysosomes for degradation. In individuals with a LAL enzyme defect, the hydrolysis of triglycerides and cholesterol esters is reduced or absent, resulting in the accumulation of free cholesterol and fatty acids in the lysosomes of Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. The absence of free cytoplasmic cholesterol then leads to reduced feedback inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in hepatocytes, an enzyme that controls the rate of the cholesterol synthesis pathway.15,132

In the present study, dyslipidemia was present in most of the reported cases. An increased triglycerides concentration was the main lipid alteration in early-onset disease. Most of the patients have normal serum cholesterol, although high levels of LDL and depressed HDL cholesterol concentrations were also present in some patients. Elevated LDL and VLDL cholesterol are typical of CESD, and metabolic changes lead to a characteristic increase in total serum cholesterol and low HDL levels. There is an increase in triglyceride concentrations, a decrease in HDL cholesterol and qualitative changes in LDL, with consequent high cardiovascular risk.133

The lysosomal accumulation of cholesterol esters and triglycerides in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and macrophages generate diffuse steatosis, which is a potent inducer of liver fibrosis and micronodular cirrhosis.1,134 On macroscopic examination, the liver has a bright orange-yellowish appearance due to the storage of lysosomal lipids.123,135 Bernstein et al.,1 in a review of 135 cases of CESD reported in the literature, show that all their reported cases had significant liver disease, characterized by microvesicular steatosis with progression to micronodular cirrhosis and liver failure. In the present scope review, all 120 biopsies showed alterations. Microvesicular steatosis was identified in 29.3% of the CESD liver biopsies and 11% of the patients with Wolman disease. Additional findings included intracytoplasmic glycogen, Kupffer cell vacuolization and lipid deposition, hepatocyte lipid deposition, hepatocyte vacuolization, Kupffer cell lipid deposition, portal inflammation, portal fibrosis, and cirrhosis, as described in Supplementary Table S3. Cholesterol crystals were observed under polarized light in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells in 32% of the reported patients. As this is considered a guiding diagnostic finding for LAL-D, it is suggested that this assessment be performed routinely when the disease is suspected.1,123,136

A characteristic of the early-onset disease is diffuse bilateral calcification of the adrenal glands. The calcified adrenals can be detected on simple radiography, ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance.16,21,129,137 In this present study, this characteristic was present in 74.6% of the patients with the early-onset variant. However, it was also found with a prevalence of 4.8% in patients with late-onset disease, reinforcing that this characteristic must be investigated in both disease spectra.

Performing upper digestive endoscopy in patients with acid lipase deficiency can contribute to the diagnosis, being essential in patients with progression of liver disease and presence of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. As seen in this present review, all biopsied patients had evidence of a lipid storage disease, reinforcing the conduct that biopsies should be performed during upper digestive endoscopy regardless of macroscopic changes.

Fatal outcomes of LAL-D can be avoided when there is a high degree of clinical suspicion and this rare hereditary disease is included in the differential diagnosis of hepatomegaly, lipid metabolism disorder and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with fibrosis or cirrhosis. Sebelipase alfa should be introduced to patients early to prevent cirrhosis, cardiovascular complications and death.11

LimitationsThis scope review investigated the clinical and laboratory characteristics of LAL-D. This study is the largest series of cases describing the onset and diagnosis of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency in childhood including the disease spectra of Wolman disease and CESD. The authors’ limitations were the inclusion of observational studies such as case reports and case series, which have a low recognized level of evidence, and the exclusion of studies with patients older than 18. The authors recognize that using this age cut-off point without assessing the natural history of LAL-D across all age groups may have led to the exclusion of adult patients for which the disease onset occurred during childhood or early childhood. However, the articles were carefully evaluated to extract as much information as possible in order to create a robust database of patients with acid lipase deficiency in childhood and adolescence.

ConclusionThe diagnosis of LAL-D in children and adolescents must be made early since the start of the treatment changes patients' quality of life in the long term. Symptoms of LAL-D such as hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, dyslipidemia, anemia, and elevated transaminases are common in pediatric practice. The present review suggests that simple symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, and splenomegaly may be correlated and serve as a starting point for investigating LAL-D. This review also emphasizes that familial lymphohistiocytosis should be part of the differential diagnosis with LAL-D, and that all patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be submitted to intestinal biopsies.

The authors would like to thank the librarian Maria Gorete Manteguti Savi for instructions on the search strategy for the first stage of this scoping review. The authors also thank Silvia Modesto Nassar for her invaluable help with the statistical analysis.