to describe the case-fatality rate (CFR) and risk factors of death in children with community-acquired acute pneumonia (CAP) in a pediatric university hospital.

Methoda longitudinal study was developed with prospective data collected from 1996 to 2011. Patients aged 1 month to 12 years were included in the study. Those who left the hospital against medical orders and those transferred to ICU or other units were excluded. Demographic and clinical-etiological characteristics and the initial treatment were studied. Variables associated to death were determined by bivariate and multivariate analysis using logistic regression.

Resultsa total of 871 patients were selected, of whom 11 were excluded; thus 860 children were included in the study. There were 26 deaths, with a CFR of 3%; in 58.7% of these, penicillin G was the initial treatment. Pneumococcus was the most common pathogen (50.4%). From 1996 to 2000, there were 24 deaths (93%), with a CFR of 5.8% (24/413). From 2001 to 2011, the age group of hospitalized patients was older (p = 0.03), and the number of deaths (p = 0.02) and the percentage of disease severity were lower (p = 0.06). Only disease severity remained associated to death in the multivariate analysis (OR = 3.2; 95%CI: 1.2-8.9; p = 0.02).

Conclusionwhen the 1996-2000 and 2001-2011 periods were compared, a significant reduction in CFR was observed in the latter, as well as a change in the clinical profile of the pediatric inpatients at the institute. These findings may be related to the improvement in the socio-economical status of the population. Penicillin use did not influence CFR.

descrever a taxa de letalidade (TL) e os fatores de risco de óbito em crianças com pneumonia grave adquirida na comunidade (CAP) em um hospital universitário pediátrico.

Métodofoi desenvolvido um estudo longitudinal com dados prospectivos coletados de 1996 a 2011. Foram incluídos no estudo pacientes com idade entre 1 mês e 12 anos de idade. Foram excluídos aqueles que deixaram o hospital desconsiderando as recomendações médicas e aqueles transferidos para UTI ou outras unidades. Foram estudadas as características demográficas, clínicas e etiológicas e o tratamento inicial. As variáveis associadas a óbito foram determinadas por análise bivariada e multivariada utilizando regressão logística.

Resultadosfoi selecionado um total de 871 pacientes, dos quais 11 foram excluídos; assim, foram incluídas no estudo 860 crianças. Houve 26 óbitos, com uma TL de 3%; em 58,7% desses, penicilina G foi o tratamento inicial. Pneumococo foi o patógeno mais comum (50,4%). De 1996 a 2000, houve 24 óbitos (93%), com uma TL de 5,8% (24/413). De 2001 a 2011, a faixa etária de pacientes internados foi mais velha (p = 0,03) e o número de óbitos (p = 0,02) e o percentual de gravidade das doenças foram menores (p = 0,06). Apenas a gravidade das doenças continuou associada a óbito na análise multivariada (RC = 3,2; IC de 95%: 1,2-8,9; p = 0,02).

Conclusãoquando os períodos de 1996-2000 e 2001-2011 foram comparados, foi observada uma redução significativa na TL no último período, bem como uma alteração no perfil clínico dos pacientes hospitalizados no instituto. Esses achados podem estar relacionados à melhora na situação socioeconômica da população. O uso de penicilina não influenciou a TL.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remains the leading cause of death in children worldwide, contributing to approximately 14% of deaths in children from 1 month to 5 years of age. It is a critical illness for countries to achieve part IV of the Millennium Development Goals: reduce by two thirds the mortality rate among children aged < 5 years from 1990 to 2015.1

Most children aged < 5 years have four to six acute respiratory infections (ARIs) per year; 2% to 3% of ARIs develop into CAP.2,3

Although mortality and morbidity rates due to CAP in children aged < 5 years have been decreasing worldwide, in developing countries the mortality is still a serious public health problem, with approximately 1.2 million deaths per year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 2001 and 2003, 20% of deaths among children aged < 5 years in developing countries were caused by CAP. According to Health Informatics Department (DATASUS), there was a significant reduction in mortality from CAP in children aged < 5 years in the period 1991-2007 in Brazil. 2–6 However, in spite of this reduction, most hospitalizations for pneumonia in Brazil are of children aged < 5 years and the elderly.

Pneumococcus is the main etiological agent of CAP in children aged < 5 years in developing and developed countries. The most commonly isolated etiological agents in children with CAP in developing countries are: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus.7–10In most CAP cases requiring hospitalization, treatment involves the choice of antibiotic therapy and supportive care: oxygen therapy, adequate hydration, and nutrition. As it is usually difficult to identify the causative agent, the start of antibiotic therapy is empirical and the choice is based on personal experience or previous studies on the etiology of CAP.7,8,11–14This study aimed to describe the case-fatality rate (CFR), the clinical-etiological profile, the initial treatment with antibiotics, and the factors associated with death in children admitted to a university pediatric hospital with CAP from 1996 to 2011. The current knowledge on this subject is limited, and the results will contribute to improving the care of children with this disease.

MethodsThis was a longitudinal, hospital-based observational study, with prospective data collection from January of 1996 to December of 2011 at the Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira (IPPMG) of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. IPPMG is the only university hospital that treats exclusively pediatric patients from Rio de Janeiro, and it is a referral institution in the city of Rio de Janeiro. It offers free emergency service, 900 consultations/month, pediatric intensive care unit (PICU, since September of 2007), wards, approximately 1,000 admissions/year, and outpatient pediatric service, with approximately 3,200 consultations/month.

Patients aged between 1 month and 12 years of age, hospitalized in IPPMG due to severe CAP, were included regardless of the presence of wheezing, according to the WHO classification.14 Patients who were discharged against medical advice, transferred to other health facilities, or more recently to the PICU, or patients whose data records were incomplete were excluded.

All children had one or more of the following signs and symptoms associated with radiological condensation abnormalities: cough, high respiratory rate, sub costal depression, cyanosis, flaring of the nostrils, moaning, irritability/lethargy, torpor, and shock. The variable of interest was death (mortality) in relation to the type of antibiotic used in the treatment. The following variables were studied: age (younger than 1 year, between 1 and 5 years, and 5 years or older; also categorized as as younger than five years or five years and older); gender; hospitalization time (categorized as less than 14 days or 14 days or more; or as zero to six, seven to 14, and more than 14 days); severe illness at admission (presence of at least one of the following findings concomitant with CAP classified as severe according to the WHO criteria: signs of sepsis, respiratory failure, cyanosis, flaring of the nostrils, moaning, torpor/coma, irritability/torpor, or shock);8,14 initial treatment with antibiotics (penicillin or others);nutritional status, which considered the 2002 weight/age criterion of the Brazilian Ministry of Health15 to classify the child as malnourished (underweight or very low weight for age) and normal weight; comorbidity (present when the child had any concomitant disease, usually chronic, undergoing treatment at the IPPMG, such as: wheezing, persistent asthma, recurrent pneumonia, chronic pneumonia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, AIDS, systemic rheumatoid arthritis, genetic syndrome, encephalopathy, heart disease, among other chronic diseases and associations between them); pleural effusion (radiographic evidence); and type of agent (isolated from the analysis of material assessed for direct examination and culture sputum, blood, pleural fluid, bronchoalveolar wash/aspirate).

Chest X-rays were analyzed by a radiologist at the institution, adopting the standard proposed by the WHO.16

Data were collected systematically, daily, from the first day of admission to hospital discharge, by postgraduate students of the Department of Pediatric Pulmonology of the IPPMG, trained for such assignment and under the supervision of professors of the service. The forms prepared for this purpose were previously tested and periodically compared with data from medical records, by researchers other than those responsible for the original collection. The protocol and data collection system were implemented and tested in a pilot project.

Data were transferred to an electronic database and analyzed using Stata software, release 7.0. Descriptive analysis was performed for the entire period, generating frequency distributions of the selected variables. Then the bivariate analysis was performed, with death as the outcome. Variables associated with death (p < 0.05) in the bivariate analysis were submitted to multivariate analysis using logistic regression. Odds ratios (ORs) were used as the measure of association, with a 95% confidence interval, and the chi-squared test was used for statistical inference; significance was set at p < 0.05.

Since most deaths occurred in the period of 1996-2000, it was decided to compare the two periods (1996-2000 and 2001-2011) in relation to mortality, clinical profile, and initial treatment, and to analyze the factors associated with death in the first period.

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of IPPMG.

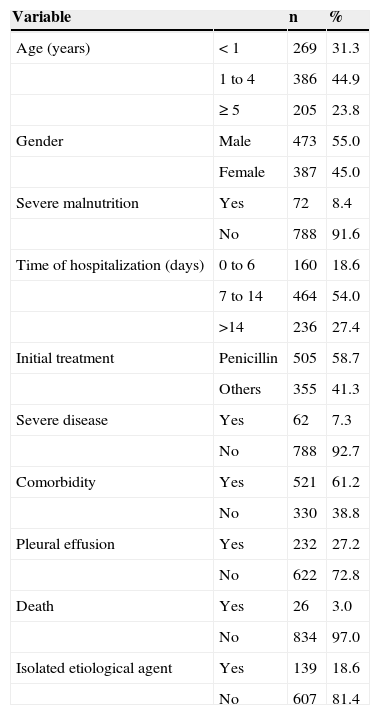

ResultsA total of 871 children were studied; nine were excluded due to transfer to another health facility, one due to to PICU admission, and one due to discharge against medical advice, totaling 860 children. The clinical profile, initial therapy, and CFR of these children are shown in Table 1. There were 26 deaths, with a total CFR of 3%.

Case-fatality rate, clinical profile, and initial treatment with antibiotics of 860 children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia from 1996 to 2011. Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira (IPPMG) of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2012.

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 1 | 269 | 31.3 |

| 1 to 4 | 386 | 44.9 | |

| ≥ 5 | 205 | 23.8 | |

| Gender | Male | 473 | 55.0 |

| Female | 387 | 45.0 | |

| Severe malnutrition | Yes | 72 | 8.4 |

| No | 788 | 91.6 | |

| Time of hospitalization (days) | 0 to 6 | 160 | 18.6 |

| 7 to 14 | 464 | 54.0 | |

| >14 | 236 | 27.4 | |

| Initial treatment | Penicillin | 505 | 58.7 |

| Others | 355 | 41.3 | |

| Severe disease | Yes | 62 | 7.3 |

| No | 788 | 92.7 | |

| Comorbidity | Yes | 521 | 61.2 |

| No | 330 | 38.8 | |

| Pleural effusion | Yes | 232 | 27.2 |

| No | 622 | 72.8 | |

| Death | Yes | 26 | 3.0 |

| No | 834 | 97.0 | |

| Isolated etiological agent | Yes | 139 | 18.6 |

| No | 607 | 81.4 |

Of the 860 children studied, 58.7% were initially treated with penicillin G. Pneumococcus was the isolated etiological agent in 50.4% of cases (70/139), including in pneumonia with pleural effusion, followed by Staphylococcus aureus in 11.5% (16/139). In the period between 1996-2000, there were 24 deaths (93% of total), with a CFR of 5.8% (24/413).

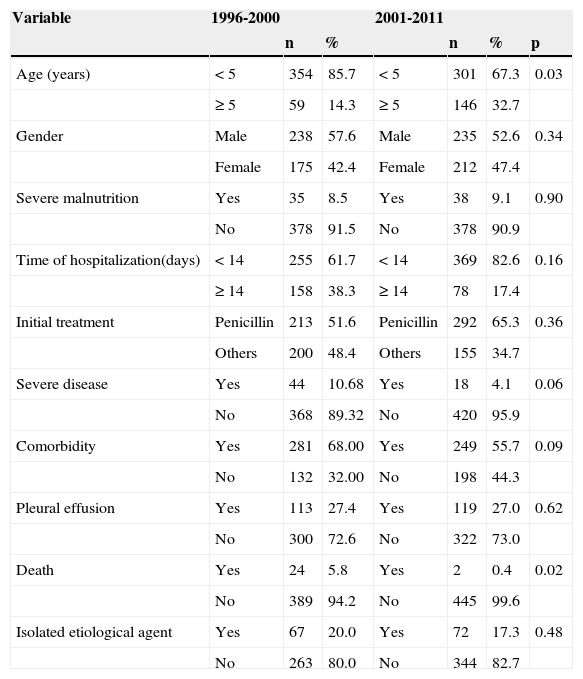

From 1996 to 2000, there were 413 hospitalizations; in the ten following years, 447. The mean number of admissions/year from 1996 to 2000 was 103, and from 2001 to 2011, 45. The clinical profile, initial therapy, and CFR in children hospitalized in both periods are shown in Table 2. From 2001 to 2011, the mean age was higher (p = 0:03) and the number of deaths was lower (p = 0.02) when compared to the first period. The percentage of severity was higher in the first period (10.6 to 4.1), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Case fatality rate, clinical profile, and initial treatment with antibiotics of 860 children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. 1996-2000 and 2001-2011. Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira (IPPMG) of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012.

| Variable | 1996-2000 | 2001-2011 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | |||

| Age (years) | < 5 | 354 | 85.7 | < 5 | 301 | 67.3 | 0.03 |

| ≥ 5 | 59 | 14.3 | ≥ 5 | 146 | 32.7 | ||

| Gender | Male | 238 | 57.6 | Male | 235 | 52.6 | 0.34 |

| Female | 175 | 42.4 | Female | 212 | 47.4 | ||

| Severe malnutrition | Yes | 35 | 8.5 | Yes | 38 | 9.1 | 0.90 |

| No | 378 | 91.5 | No | 378 | 90.9 | ||

| Time of hospitalization(days) | < 14 | 255 | 61.7 | < 14 | 369 | 82.6 | 0.16 |

| ≥ 14 | 158 | 38.3 | ≥ 14 | 78 | 17.4 | ||

| Initial treatment | Penicillin | 213 | 51.6 | Penicillin | 292 | 65.3 | 0.36 |

| Others | 200 | 48.4 | Others | 155 | 34.7 | ||

| Severe disease | Yes | 44 | 10.68 | Yes | 18 | 4.1 | 0.06 |

| No | 368 | 89.32 | No | 420 | 95.9 | ||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 281 | 68.00 | Yes | 249 | 55.7 | 0.09 |

| No | 132 | 32.00 | No | 198 | 44.3 | ||

| Pleural effusion | Yes | 113 | 27.4 | Yes | 119 | 27.0 | 0.62 |

| No | 300 | 72.6 | No | 322 | 73.0 | ||

| Death | Yes | 24 | 5.8 | Yes | 2 | 0.4 | 0.02 |

| No | 389 | 94.2 | No | 445 | 99.6 | ||

| Isolated etiological agent | Yes | 67 | 20.0 | Yes | 72 | 17.3 | 0.48 |

| No | 263 | 80.0 | No | 344 | 82.7 | ||

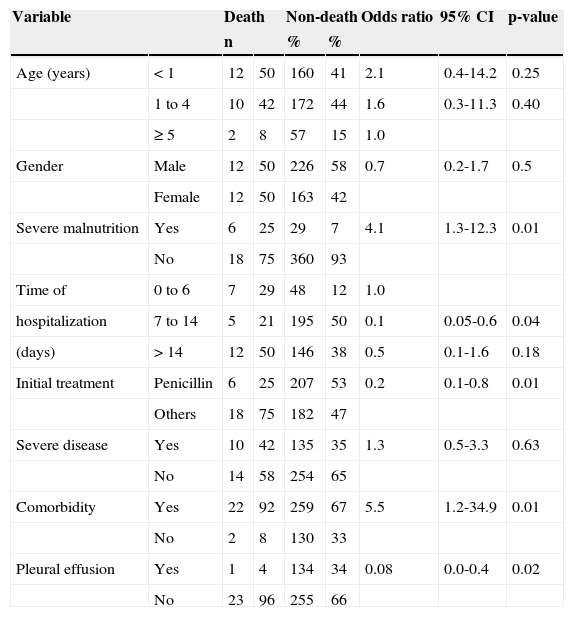

In the bivariate analysis, the following variables were statistically associated with death: presence of malnutrition, initial treatment with antimicrobial other than penicillin, presence of comorbidity, and presence of pleural effusion (Table 3). As most of these variables indicate severity, the association between them and the variable severe illness was analyzed, but it was not statistically significant. It was observed that severe disease was associated with comorbidity (OR = 17.8, 95% CI: 12.0-26.3) and the occurrence of pleural effusion (OR = 4.6, 95% CI: 2.7-6.0), which caused this variable to remain in the multivariate analysis, in addition to others associated with death in the bivariate analysis.

Association between death and selected variables in 413 children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia, 1996-2000. Results of the bivariate analysis. Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira (IPPMG) of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012.

| Variable | Death | Non-death | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | % | ||||||

| Age (years) | < 1 | 12 | 50 | 160 | 41 | 2.1 | 0.4-14.2 | 0.25 |

| 1 to 4 | 10 | 42 | 172 | 44 | 1.6 | 0.3-11.3 | 0.40 | |

| ≥ 5 | 2 | 8 | 57 | 15 | 1.0 | |||

| Gender | Male | 12 | 50 | 226 | 58 | 0.7 | 0.2-1.7 | 0.5 |

| Female | 12 | 50 | 163 | 42 | ||||

| Severe malnutrition | Yes | 6 | 25 | 29 | 7 | 4.1 | 1.3-12.3 | 0.01 |

| No | 18 | 75 | 360 | 93 | ||||

| Time of | 0 to 6 | 7 | 29 | 48 | 12 | 1.0 | ||

| hospitalization | 7 to 14 | 5 | 21 | 195 | 50 | 0.1 | 0.05-0.6 | 0.04 |

| (days) | > 14 | 12 | 50 | 146 | 38 | 0.5 | 0.1-1.6 | 0.18 |

| Initial treatment | Penicillin | 6 | 25 | 207 | 53 | 0.2 | 0.1-0.8 | 0.01 |

| Others | 18 | 75 | 182 | 47 | ||||

| Severe disease | Yes | 10 | 42 | 135 | 35 | 1.3 | 0.5-3.3 | 0.63 |

| No | 14 | 58 | 254 | 65 | ||||

| Comorbidity | Yes | 22 | 92 | 259 | 67 | 5.5 | 1.2-34.9 | 0.01 |

| No | 2 | 8 | 130 | 33 | ||||

| Pleural effusion | Yes | 1 | 4 | 134 | 34 | 0.08 | 0.0-0.4 | 0.02 |

| No | 23 | 96 | 255 | 66 | ||||

CI, confidence interval.

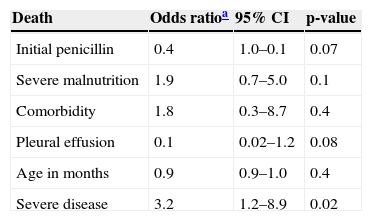

It was also decided to maintain the variable age (in months), since the difference in risk of death in younger children has been proven.1 In the multivariate analysis, severe disease was the only single variable that remained significantly associated with death (Table 4).

Association between death and selected variables in 413 children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia, 1996-2000. Results of the multivariate analysis. Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira (IPPMG) of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012.

| Death | Odds ratioa | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial penicillin | 0.4 | 1.0–0.1 | 0.07 |

| Severe malnutrition | 1.9 | 0.7–5.0 | 0.1 |

| Comorbidity | 1.8 | 0.3–8.7 | 0.4 |

| Pleural effusion | 0.1 | 0.02–1.2 | 0.08 |

| Age in months | 0.9 | 0.9–1.0 | 0.4 |

| Severe disease | 3.2 | 1.2–8.9 | 0.02 |

CI, confidence interval.

This study, conducted in a university pediatric referral center in Rio de Janeiro from 1996 to 2011, showed that the CFR in children with CAP was low (3%), and that the disease affected mainly children younger than 5 years (76.2%) initially treated with penicillin (58.7%) and with a comorbidity (61.2%). However, most deaths occurred in the period 1996-2000 (93%), with a CFR of 5.8% in this period, when a greater number of hospitalizations for CAP, higher incidence of hospitalization for CAP in younger children, and more cases of severe disease were observed.

The CFR observed in the study period can be considered low, especially because this is a referral center for children with severe disease and comorbidities. Recent studies performed in low-income countries have shown CFR ranging from 5.8% to 8.2%.1,17–19However, considering the two studied periods, distinct differences in profile can be observed, both in CFR and in age and severity on admission, with a trend to shorter hospital stay and lower severity on admission in the second period (2001-2011), raising questions regarding the reason for this difference.

Important changes occurred in Brazil in recent years that may partly explain this profile change. In the period of 1997-2008, which covers most of the present study, the infant mortality rate (IMR) of the country decreased from 31.9 to 17.56, whereas in the state of Rio de Janeiro it ranged from 24.0 to 14.31. The mortality rate in children younger than 5 years (MRY5) in the period of 2000 to 2008 ranged from 31.99 to 20.49 in Brazil and from 22.54 to 16.72 in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The increase in vaccination coverage achieved rates > 90%.20–22Additionally, a trend of improvement in socioeconomic status was observed among the parents, as demonstrated by the decrease in unemployment rates, reduction of illiteracy rate from 34% in the 1990s to 10% in 2008, and of the poverty rate from 68% in 1970 to 31% in 2008, on account of social programs such as the income distribution program of the Brazilian government, which has benefited over 10 million Brazilians, and of the increase, with real gains, in the minimum wage. The Gini index, which measures income distribution, showed progressive improvement from 2003 to 2011, whereas in the same period, the percentage of population in poverty decreased from 24.4% to 10.2%.21

According to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF),20 CAP is a disease associated with poverty, as well as environmental factors, malnutrition, and difficulty in accessing the local health system. Many deaths would be prevented with exclusive breastfeeding, adequate nutrition, vaccination, washing of hands with soap and water, and availability of water fit for consumption and basic sanitation facilities. The improvement of these sanitation conditions in the country, due to the improvement in socioeconomic status, may have contributed to the change in the profile observed in hospitalizations for CAP at the IPPMG.

Regarding mortality, the presence of severity on admission was the only single variable associated with death, similarly to what was found in recent studies performed in low-income countries.17–20 The abovementioned demographic, epidemiological, and nutritional transitions were certainly responsible for the changes in morbidity and mortality demonstrated here.

Regarding the children who died in the period 1996-2000, 42% had severe disease and 92% were younger than 5 years. Bacterial isolation was achieved in 62%, showing the severity of infection with hematogenous dissemination of the infection.

These findings highlight the importance of severe disease on CFR of children hospitalized with CAP, and suggest that it is safe to start treatment with penicillin G. This finding is similar to that found by the multicenter study on the etiology of CAP and penicillin resistance with the participation of several countries in South America and the Caribbean, including the IPPMG. In that study, S. pneumoniae fully resistant to penicillin was not found, which provided support to the recommendation of penicillin or ampicillin as drugs of choice for the treatment of CAP, even for penicillin-resistant bacteria, in areas where the minimum inhibitory concentration is not higher than 2μg/mL, as in Brazil. 23

Similarly, Simbalista et al., 24 in a retrospective study of 154 children hospitalized with CAP in a university hospital in Salvador, Brazil, from 2002 to 2005, concluded that penicillin G, used to treat most cases, was highly effective, with improvement within the first 48hours and no occurrence of deaths.

One limitation of the present study was the incapacity to assess the possible impact of vaccination status on the CFR of CAP cases studied. As the conjugate vaccination against pneumococcal agents was only incorporated into the immunization schedule of Brazilian children in 2010, such investigation was not feasible.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a significant reduction in CFR in children with CAP in the period 2001-2011, with a change in the profile of children hospitalized for this disease at IPPMG. It is suggested that these findings are related to changes in the socioeconomic profile of the population in this period.25 The use of penicillin in the empiric treatment of CAP was not related to the observed CFR.

FundingThe present study received resources from the project funded by the Pan American Health Organization (1998- 2003).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferreira S, Sant’Anna CC, March MdF, Santos MA, Cunha AJ. Lethality by pneumonia and factors associated to death. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:92–97.

Study conducted at the Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.