To assess the prevalence and risks of underweight, stunting and wasting by gestational age in newborns of the Jujuy Province, Argentina at different altitude levels.

MethodsLive newborns (n=48,656) born from 2009–2014 in public facilities with a gestational age between 24+0 to 42+6 weeks. Phenotypes of underweight (weight/age), stunting (length/age) and wasting (body mass index/age) were calculated using INTERGROWTH-21st standards. Risk factors were maternal age, education, body mass index, parity, diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, tuberculosis, prematurity, and congenital malformations. Data were grouped by the geographic altitude: ≥2.000 or <2.000m.a.s.l. Chi-squared test and a multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed to estimate the risk of the phenotypes associated with an altitudinal level ≥2.000m.a.s.l.

ResultsThe prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting were 1.27%, 3.39% and 4.68%, respectively, and significantly higher at >2.000m.a.s.l. Maternal age, body mass index >35kg/m2, hypertension, congenital malformations, and prematurity were more strongly associated with underweight rather than stunting or wasting at ≥2.000m.a.s.l.

ConclusionsUnderweight, stunting, and wasting risks were higher at a higher altitude, and were associated with recognized maternal and fetal conditions. The use of those three phenotypes will help prioritize preventive interventions and focus the management of fetal undernutrition.

Avaliar a prevalência e os riscos de recém-nascidos abaixo do peso, baixa estatura e emaciação por idade gestacional da Província de Jujuy, Argentina, em diferentes níveis de altitude.

MétodosRecém-nascidos vivos (n = 48.656) nascidos entre 2009 e 2014 em instalações públicas entre 24+0-42+6 semanas de idade gestacional. Os fenótipos de abaixo do peso (< P3 peso/idade), baixa estatura (< P3 comprimento/idade) e emaciação (< P3 índice de massa corporal/idade) foram calculados com os padrões do INTERGROWTH-21st. Os fatores de risco foram idade materna, escolaridade, índice de massa corporal, paridade, diabetes, hipertensão, pré-eclâmpsia, tuberculose, prematuridade e malformações congênitas. Os dados foram agrupados pela altitude geográfica: ≥ 2.000 ou < 2.000 m.a.s.l. O teste qui-quadrado e a análise de regressão logística multivariada foram feitos para estimar o risco dos fenótipos associados ao nível de altitude ≥ 2.000 m.a.s.l.

ResultadosA prevalência de abaixo do peso, baixa estatura e emaciação foi de 1,27%, 3,39% e 4,68%, respectivamente, significativamente maiores em > 2.000 m.a.s.l. A idade materna, índice de massa corporal > 35kg/m2, hipertensão, malformações congênitas e prematuridade foram mais fortemente associados a abaixo do peso e não a baixa estatura ou emaciação em ≥2.000 m.a.s.l.

ConclusõesOs riscos de abaixo do peso, baixa estatura e emaciação foram maiores em altitude mais elevada e foram associados a condições maternas e fetais reconhecidas. O uso desses três fenótipos ajudará a priorizar as intervenções preventivas e focar no manejo da desnutrição fetal.

Several anthropometric measures are widely used by neonatologists to assess newborn nutrition, such as low birth weight (<2500g), small for gestational age (SGA, birth weight [BW] below 10th percentile for gestational age [GA]), Ponderal Index1 (PI, weight/length3), proportionality (estimated by z-transformation of PI)2 and placental insufficiency3 However, none is synonymous with intrauterine growth restriction.4

Neonatal anthropometry is characterized by being inexact and by the lack of validation and consensus of its available indexes.5 In addition, there is no correspondence and harmonization between the different criteria to assess pre- and postnatal nutritional status for constant and continuous growth monitoring in the different stages of ontogenesis.6

The International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st Project – IG-21) recently published the standards for newborn weight, length and head circumference.7 It is a cross-sectional, multicenter study on size at birth by sex and GA, conducted with the same prescriptive approach and methodological design as those used in establishing WHO standards.8 IG-21 suggests that low weight at a given GA may result from stunting (short length for age, reflecting linear growth restriction), wasting (low weight for length, or low body mass index [BMI] for age, often reflecting recent weight loss), or both phenotypes. Those are two distinct phenotypes, with different timing and duration of causal insults, specific risk factors, and varied distributions across populations and different prognoses.9

Several anthropometry studies on children and adolescents from altitude ecosystems indicate that this population, compared to those living closer to sea level, is shorter and lighter.10,11 Particularly in newborn infants of Jujuy, birth weight, as well as the indicators of severe intrauterine growth impairment are independently associated with geographic altitude.2,12–15 However, most studies of altitude effect on fetal growth are limited to term newborn infants.

The objective was to use the IG-21 standard to assess the prevalence and common risks factors of underweight, stunting, and wasting by gestational age (GA) in newborn infants of Jujuy associated with high altitudinal levels.

Material and methodsStudy populationThis was an observational, analytical, and retrospective study conducted on consecutive births registered by the Perinatal Informatics System (SIP, Ministry of Health of the Province of Jujuy, Argentina) between 2009 and 2014. Exclusion criteria were (1) GA <24+0 and >42+6 weeks; (2) lack of data on weight, height, GA, sex, and maternal place of residence during pregnancy; (3) twin pregnancy. Alexander's criterion was applied to correct incompatibilities between birth weight and gestational age.16

Data assessmentData were grouped according to geographic altitude of the maternal place of residence into a low altitude (LA) group (<2000m.a.s.l.) and a high altitude (HA) group (≥2000 m.a.s.l.). Newborn nutritional status was determined with IG-21 standard, using the following phenotypes at birth: (a) Stunting (<3rd percentile length/GA); (b) Wasting (<3rd percentile BMI [Kg/m2]/GA),9 and (c) a third phenotype – not included in the IG-21 standard –, underweight (BW <3rd percentile for age and sex), indicating a severe insult. This eliminates the chance of erroneous inclusion of a normal newborn in the lower BW distribution. Because the IG-21 Project does not provide an assessment of BMI below 33+0 weeks GA, the current study's data included underweight and stunting between 24+0 and 42+6 weeks, and wasting between 33+0 and 42+6 weeks.

The following characteristics were analyzed: (1) maternal biological and sociodemographic characteristics: age (<20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–35 and ≥35 years), parity (0, 1, 2 and ≥3), BMI (<18.5 undernutrition; 18.5–24.9 normal nutrition; 25.0–29.9 overweight; 30–34.9 obesity type I; and ≥35kg/m2 obesity type II), and education (<8; 8–11 and ≥12 years); (2) diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia and tuberculosis during pregnancy; and (3) sex, prematurity (<37+0 weeks) and congenital malformations for the newborns. Maternal biological and sociodemographic variables were categorical; the remainder were dichotomous.

Statistical analysisPrevalence of the different phenotypes was estimated by proportion (95% CI [confidence interval]), whereas population differences were analyzed with a chi-squared test and univariate risk: odds ratio (OR and 95% CI). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the risk of underweight, stunting, and wasting associated with altitude level (exposure variable), and adjusted for maternal age, educational level, BMI, parity, tuberculosis, diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, sex, prematurity, and congenital malformations. Low altitude was the reference. Goodness of fit was tested with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. SPSS (Version 22) and Stata (Version 11) statistical software were used. The statistical level was set at p<0.05.

Ethical issuesThe Provincial Committee of Ethics of research in health of Jujuy, Argentina, approved this study.

ResultsBetween 2009 and 2014, 79,504 live infants were born in the Jujuy Province; 57,471 were registered by SIP. After applying the selection criteria, 48,656 (84.6%, 95% CI 84.3–84.9) newborns were included in the study; of those, 16.8% (16.5–17.2) came from HA (Supplemental Digital Content [SDC] S1, Fig. 1).

Underweight, stunting and wasting prevalence were 1.27% (1.18–1.38), 3.39% (3.24–3.36), and 4.68% (4.49–4.87), respectively. The stunting plus wasting rate was 0.16% (0.12–0.20). The rate of HA underweight infants was 1.13 times higher (0.80–1.49) than the equivalent LA rate, whereas the rates for stunting and wasting were 2.68 (2.10–3.29) and 5.26 (4.61–5.95) times higher, respectively.

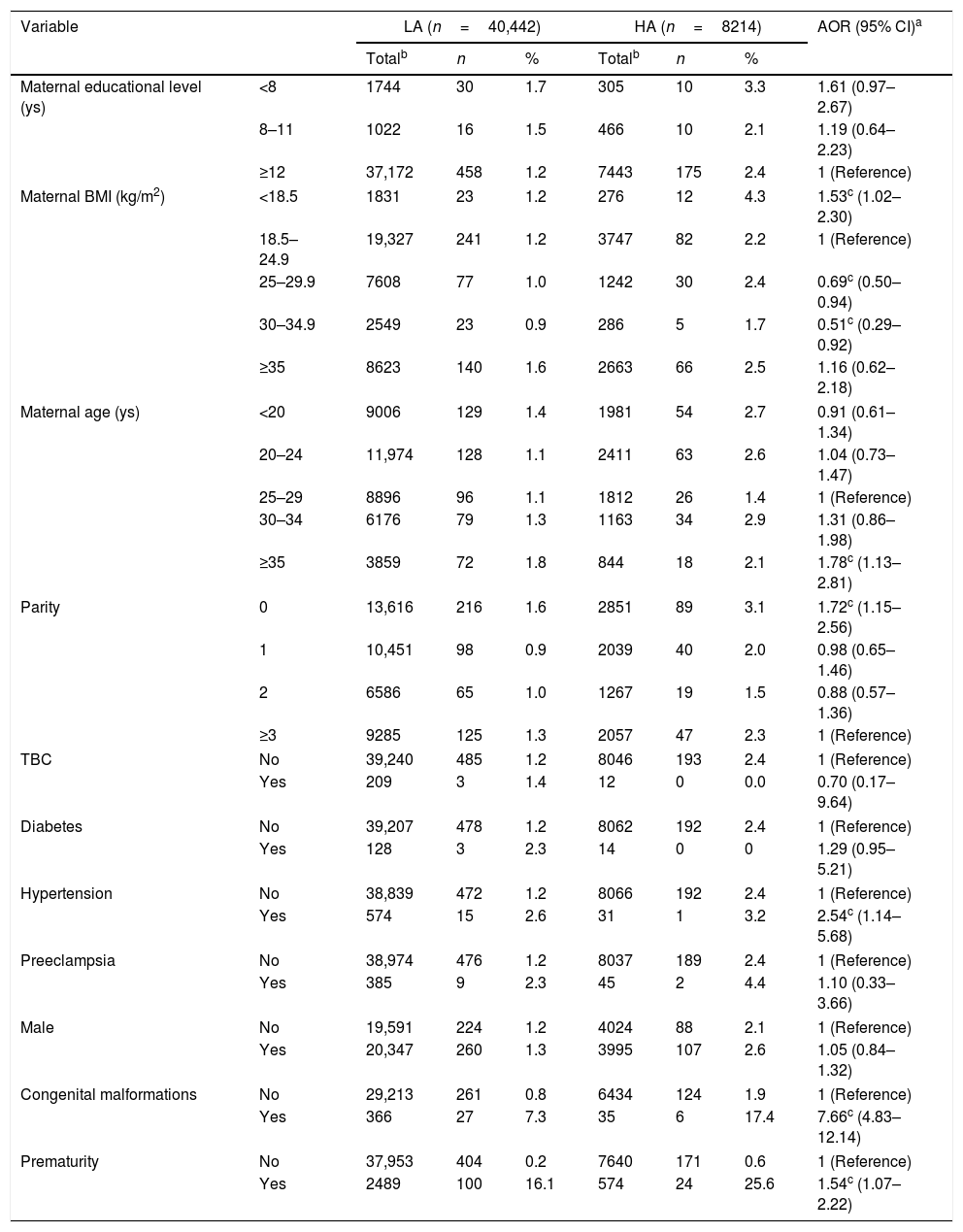

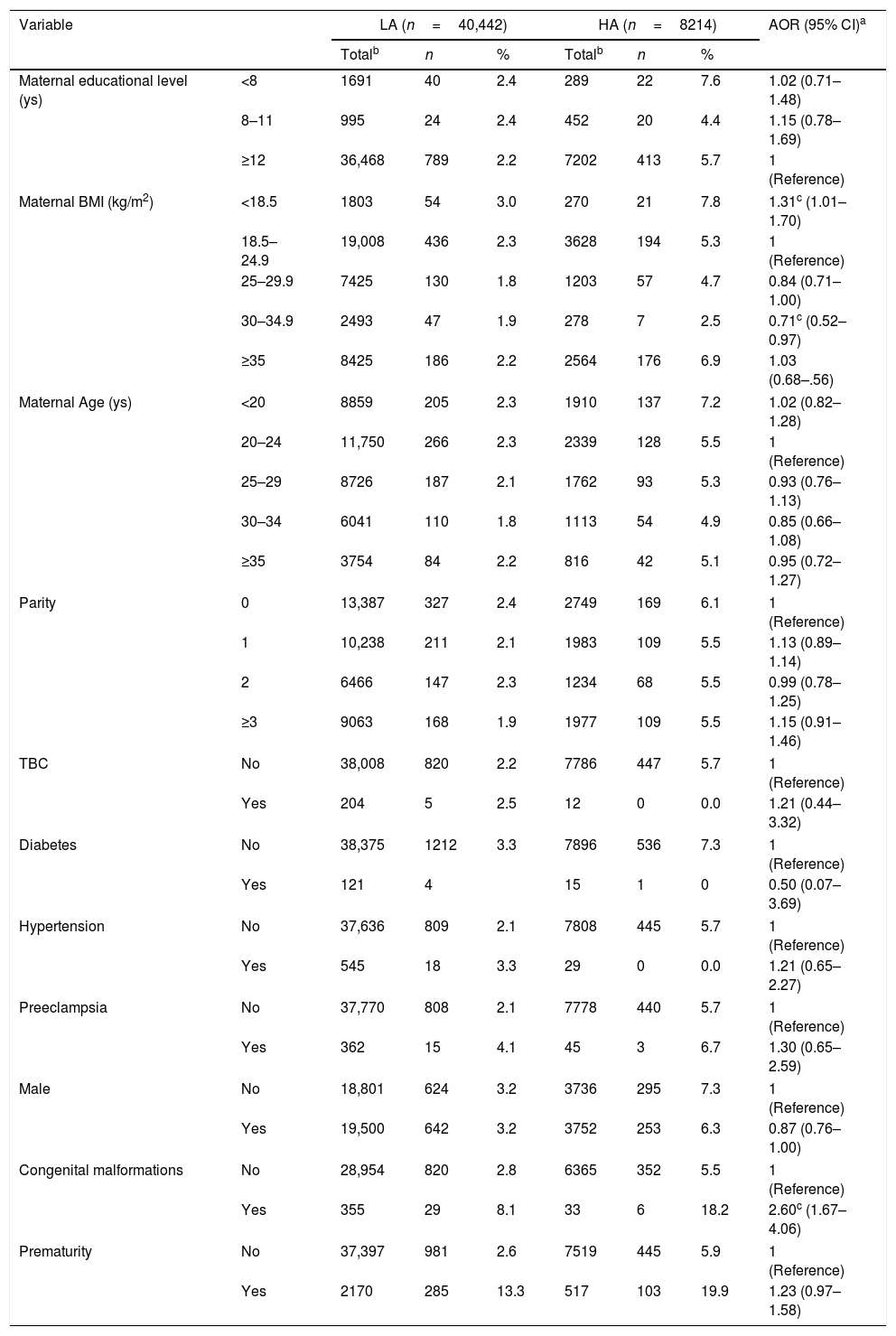

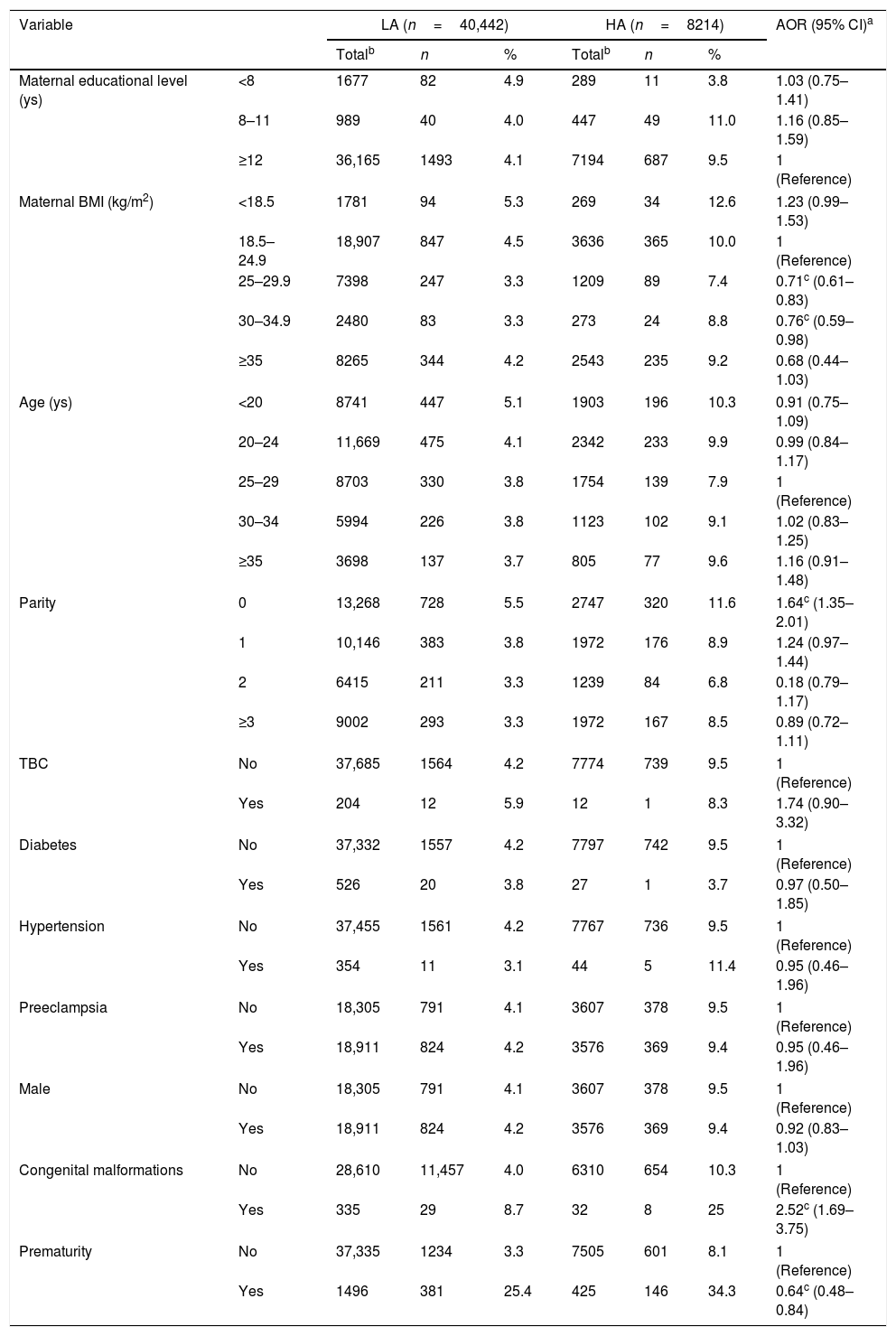

Overall, the HA mothers of underweight newborns showed significantly greater age, higher undernutrition, hypertension, prematurity and congenital malformations, but less overweight and obesity type I than the LA mothers. Pregnancies in the HA group with stunted newborns were independently associated with higher undernutrition, but less obesity type I, while wasting-affected newborns in the HA group showed less normal pregnancy nutrition, obesity type I and prematurity, but higher nulliparity and congenital malformations than the newborns of LA mothers (Table 1).

Prevalence of maternal and newborn characteristics and adjusted risk of underweight according to geographic altitude (Jujuy, Argentina, 2009–2014).

| Variable | LA (n=40,442) | HA (n=8214) | AOR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalb | n | % | Totalb | n | % | |||

| Maternal educational level (ys) | <8 | 1744 | 30 | 1.7 | 305 | 10 | 3.3 | 1.61 (0.97–2.67) |

| 8–11 | 1022 | 16 | 1.5 | 466 | 10 | 2.1 | 1.19 (0.64–2.23) | |

| ≥12 | 37,172 | 458 | 1.2 | 7443 | 175 | 2.4 | 1 (Reference) | |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 1831 | 23 | 1.2 | 276 | 12 | 4.3 | 1.53c (1.02–2.30) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 19,327 | 241 | 1.2 | 3747 | 82 | 2.2 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 25–29.9 | 7608 | 77 | 1.0 | 1242 | 30 | 2.4 | 0.69c (0.50–0.94) | |

| 30–34.9 | 2549 | 23 | 0.9 | 286 | 5 | 1.7 | 0.51c (0.29–0.92) | |

| ≥35 | 8623 | 140 | 1.6 | 2663 | 66 | 2.5 | 1.16 (0.62–2.18) | |

| Maternal age (ys) | <20 | 9006 | 129 | 1.4 | 1981 | 54 | 2.7 | 0.91 (0.61–1.34) |

| 20–24 | 11,974 | 128 | 1.1 | 2411 | 63 | 2.6 | 1.04 (0.73–1.47) | |

| 25–29 | 8896 | 96 | 1.1 | 1812 | 26 | 1.4 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 30–34 | 6176 | 79 | 1.3 | 1163 | 34 | 2.9 | 1.31 (0.86–1.98) | |

| ≥35 | 3859 | 72 | 1.8 | 844 | 18 | 2.1 | 1.78c (1.13–2.81) | |

| Parity | 0 | 13,616 | 216 | 1.6 | 2851 | 89 | 3.1 | 1.72c (1.15–2.56) |

| 1 | 10,451 | 98 | 0.9 | 2039 | 40 | 2.0 | 0.98 (0.65–1.46) | |

| 2 | 6586 | 65 | 1.0 | 1267 | 19 | 1.5 | 0.88 (0.57–1.36) | |

| ≥3 | 9285 | 125 | 1.3 | 2057 | 47 | 2.3 | 1 (Reference) | |

| TBC | No | 39,240 | 485 | 1.2 | 8046 | 193 | 2.4 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 209 | 3 | 1.4 | 12 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.70 (0.17–9.64) | |

| Diabetes | No | 39,207 | 478 | 1.2 | 8062 | 192 | 2.4 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 128 | 3 | 2.3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1.29 (0.95–5.21) | |

| Hypertension | No | 38,839 | 472 | 1.2 | 8066 | 192 | 2.4 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 574 | 15 | 2.6 | 31 | 1 | 3.2 | 2.54c (1.14–5.68) | |

| Preeclampsia | No | 38,974 | 476 | 1.2 | 8037 | 189 | 2.4 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 385 | 9 | 2.3 | 45 | 2 | 4.4 | 1.10 (0.33–3.66) | |

| Male | No | 19,591 | 224 | 1.2 | 4024 | 88 | 2.1 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 20,347 | 260 | 1.3 | 3995 | 107 | 2.6 | 1.05 (0.84–1.32) | |

| Congenital malformations | No | 29,213 | 261 | 0.8 | 6434 | 124 | 1.9 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 366 | 27 | 7.3 | 35 | 6 | 17.4 | 7.66c (4.83–12.14) | |

| Prematurity | No | 37,953 | 404 | 0.2 | 7640 | 171 | 0.6 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 2489 | 100 | 16.1 | 574 | 24 | 25.6 | 1.54c (1.07–2.22) | |

Hosmer–Lemeshow chi2=4, p=0.979.

LA, low altitudinal level; HA, high altitudinal level.

Mean BW and standard deviation (SD) of the three phenotypes was 2012g (567) for underweight, 2933g (635) for stunting and 2767g (427) for wasting, while in children without nutritional deficit it was 3321g (531).

Mean GA (SD) was 37.5 (3.9) weeks for underweight, 38.6 (2.1) weeks for stunting and 39.0 (1.3) weeks for wasting. Overall prematurity rate was 9.04% (8.79–9.30): 8.01% at HA and 9.25% at LA (p<0.001).

In the Jujuy Province at HA, the underweight, stunting and wasting risks begin to appear from the 29th, 26th, and 33th weeks of gestation, respectively. The prevalence of underweight and stunting at 24+0 to 36+6 weeks was higher than at 37+0 to 42+6 weeks (p<0.001) for HA compared with LA. On the other hand, wasting prevalence at 37+0 to 42+6 weeks was higher than at 24+0 to 36+6 weeks at HA compared with LA (p<0.001, data not shown) (SDC S2, S3 and S4, Figs. 2–4).

Crude OR (95% CI) for underweight, stunting and wasting associated with HA were 1.92 (1.63–2.27), 2.21 (1.99–2.45) and 2.39 (2.18–2.62), respectively (p<0.001). After adjustment, a slight risk reduction for stunting and a risk increase for the other phenotypes were found, all statistically significant (SDC S5, Table 1). Goodness of fit models were adequate.

Tables 1–3 show maternal and newborn characteristics according to altitude, and their association (adjusted OR, AOR) with the three phenotypes. For underweight, maternal age greater or equal to 35 years, BMI lower than 18.5kg/m2, nulliparity, gestational hypertension, prematurity, and congenital malformations were independently associated with elevated risk at HA. Overweight and obesity type I were associated to lower risk at HA (Table 1).

Prevalence of maternal and newborn characteristics and adjusted risk of stunting, according to geographic altitude (Jujuy, Argentina, 2009–2014).

| Variable | LA (n=40,442) | HA (n=8214) | AOR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalb | n | % | Totalb | n | % | |||

| Maternal educational level (ys) | <8 | 1691 | 40 | 2.4 | 289 | 22 | 7.6 | 1.02 (0.71–1.48) |

| 8–11 | 995 | 24 | 2.4 | 452 | 20 | 4.4 | 1.15 (0.78–1.69) | |

| ≥12 | 36,468 | 789 | 2.2 | 7202 | 413 | 5.7 | 1 (Reference) | |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 1803 | 54 | 3.0 | 270 | 21 | 7.8 | 1.31c (1.01–1.70) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 19,008 | 436 | 2.3 | 3628 | 194 | 5.3 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 25–29.9 | 7425 | 130 | 1.8 | 1203 | 57 | 4.7 | 0.84 (0.71–1.00) | |

| 30–34.9 | 2493 | 47 | 1.9 | 278 | 7 | 2.5 | 0.71c (0.52–0.97) | |

| ≥35 | 8425 | 186 | 2.2 | 2564 | 176 | 6.9 | 1.03 (0.68–.56) | |

| Maternal Age (ys) | <20 | 8859 | 205 | 2.3 | 1910 | 137 | 7.2 | 1.02 (0.82–1.28) |

| 20–24 | 11,750 | 266 | 2.3 | 2339 | 128 | 5.5 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 25–29 | 8726 | 187 | 2.1 | 1762 | 93 | 5.3 | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | |

| 30–34 | 6041 | 110 | 1.8 | 1113 | 54 | 4.9 | 0.85 (0.66–1.08) | |

| ≥35 | 3754 | 84 | 2.2 | 816 | 42 | 5.1 | 0.95 (0.72–1.27) | |

| Parity | 0 | 13,387 | 327 | 2.4 | 2749 | 169 | 6.1 | 1 (Reference) |

| 1 | 10,238 | 211 | 2.1 | 1983 | 109 | 5.5 | 1.13 (0.89–1.14) | |

| 2 | 6466 | 147 | 2.3 | 1234 | 68 | 5.5 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | |

| ≥3 | 9063 | 168 | 1.9 | 1977 | 109 | 5.5 | 1.15 (0.91–1.46) | |

| TBC | No | 38,008 | 820 | 2.2 | 7786 | 447 | 5.7 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 204 | 5 | 2.5 | 12 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.21 (0.44–3.32) | |

| Diabetes | No | 38,375 | 1212 | 3.3 | 7896 | 536 | 7.3 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 121 | 4 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0.50 (0.07–3.69) | ||

| Hypertension | No | 37,636 | 809 | 2.1 | 7808 | 445 | 5.7 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 545 | 18 | 3.3 | 29 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.21 (0.65–2.27) | |

| Preeclampsia | No | 37,770 | 808 | 2.1 | 7778 | 440 | 5.7 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 362 | 15 | 4.1 | 45 | 3 | 6.7 | 1.30 (0.65–2.59) | |

| Male | No | 18,801 | 624 | 3.2 | 3736 | 295 | 7.3 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 19,500 | 642 | 3.2 | 3752 | 253 | 6.3 | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | |

| Congenital malformations | No | 28,954 | 820 | 2.8 | 6365 | 352 | 5.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 355 | 29 | 8.1 | 33 | 6 | 18.2 | 2.60c (1.67–4.06) | |

| Prematurity | No | 37,397 | 981 | 2.6 | 7519 | 445 | 5.9 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 2170 | 285 | 13.3 | 517 | 103 | 19.9 | 1.23 (0.97–1.58) | |

Hosmer–Lemeshow chi2=4.25, p=0.833.

LA, low altitudinal level; HA, high altitudinal level.

Prevalence of maternal and newborn characteristics and adjusted risk of wasting according to geographic altitude (Jujuy, Argentina, 2009–2014).

| Variable | LA (n=40,442) | HA (n=8214) | AOR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totalb | n | % | Totalb | n | % | |||

| Maternal educational level (ys) | <8 | 1677 | 82 | 4.9 | 289 | 11 | 3.8 | 1.03 (0.75–1.41) |

| 8–11 | 989 | 40 | 4.0 | 447 | 49 | 11.0 | 1.16 (0.85–1.59) | |

| ≥12 | 36,165 | 1493 | 4.1 | 7194 | 687 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) | |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 1781 | 94 | 5.3 | 269 | 34 | 12.6 | 1.23 (0.99–1.53) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 18,907 | 847 | 4.5 | 3636 | 365 | 10.0 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 25–29.9 | 7398 | 247 | 3.3 | 1209 | 89 | 7.4 | 0.71c (0.61–0.83) | |

| 30–34.9 | 2480 | 83 | 3.3 | 273 | 24 | 8.8 | 0.76c (0.59–0.98) | |

| ≥35 | 8265 | 344 | 4.2 | 2543 | 235 | 9.2 | 0.68 (0.44–1.03) | |

| Age (ys) | <20 | 8741 | 447 | 5.1 | 1903 | 196 | 10.3 | 0.91 (0.75–1.09) |

| 20–24 | 11,669 | 475 | 4.1 | 2342 | 233 | 9.9 | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | |

| 25–29 | 8703 | 330 | 3.8 | 1754 | 139 | 7.9 | 1 (Reference) | |

| 30–34 | 5994 | 226 | 3.8 | 1123 | 102 | 9.1 | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | |

| ≥35 | 3698 | 137 | 3.7 | 805 | 77 | 9.6 | 1.16 (0.91–1.48) | |

| Parity | 0 | 13,268 | 728 | 5.5 | 2747 | 320 | 11.6 | 1.64c (1.35–2.01) |

| 1 | 10,146 | 383 | 3.8 | 1972 | 176 | 8.9 | 1.24 (0.97–1.44) | |

| 2 | 6415 | 211 | 3.3 | 1239 | 84 | 6.8 | 0.18 (0.79–1.17) | |

| ≥3 | 9002 | 293 | 3.3 | 1972 | 167 | 8.5 | 0.89 (0.72–1.11) | |

| TBC | No | 37,685 | 1564 | 4.2 | 7774 | 739 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 204 | 12 | 5.9 | 12 | 1 | 8.3 | 1.74 (0.90–3.32) | |

| Diabetes | No | 37,332 | 1557 | 4.2 | 7797 | 742 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 526 | 20 | 3.8 | 27 | 1 | 3.7 | 0.97 (0.50–1.85) | |

| Hypertension | No | 37,455 | 1561 | 4.2 | 7767 | 736 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 354 | 11 | 3.1 | 44 | 5 | 11.4 | 0.95 (0.46–1.96) | |

| Preeclampsia | No | 18,305 | 791 | 4.1 | 3607 | 378 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 18,911 | 824 | 4.2 | 3576 | 369 | 9.4 | 0.95 (0.46–1.96) | |

| Male | No | 18,305 | 791 | 4.1 | 3607 | 378 | 9.5 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 18,911 | 824 | 4.2 | 3576 | 369 | 9.4 | 0.92 (0.83–1.03) | |

| Congenital malformations | No | 28,610 | 11,457 | 4.0 | 6310 | 654 | 10.3 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 335 | 29 | 8.7 | 32 | 8 | 25 | 2.52c (1.69–3.75) | |

| Prematurity | No | 37,335 | 1234 | 3.3 | 7505 | 601 | 8.1 | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 1496 | 381 | 25.4 | 425 | 146 | 34.3 | 0.64c (0.48–0.84) | |

Hosmer–Lemeshow chi2=1.92, p=0.983.

LA, low altitudinal level; HA, high altitudinal level.

For stunting, maternal BMI below 18.5kg/m2 and congenital malformations were independently associated with higher risk, while BMI of obesity type I showed lower risk (Table 2).

Finally, for wasting, nulliparity and congenital malformations were independently associated with higher risk, while overweight and class I obesity and prematurity were associated with lower risk (Table 3).

DiscussionIn the present study, newborns at HA in the Jujuy Province showed a significantly higher risk of underweight, stunting and wasting, and clinical and epidemiologic evidence to support the concept that they are separate anthropometric phenotypes of intrauterine origin is presented. The phenotypes differed in terms of risk factors. As expected, few conditions were associated with similar strength to underweight, stunting and wasting phenotypes; those conditions are mostly recognized as universal risk factors, i.e. GA, maternal undernutrition, obstetric history, and congenital malformations. Other factors, in particular tuberculosis, have such a wide range of severity, presentations, and timing during pregnancy that they are not phenotype-specific. On the other hand, overweight and type I obesity showed between 30% and 50% risk reduction for the three phenotypes (a well-described effect that is due to increased birth weight and fat deposition).

No comparable local records exist on the prevalence of nutritional phenotypes in newborns evaluated for GA using IG-21, except for the underweight phenotype.17 It is worth noting that, in this study,17 the prevalence of underweight calculated from birth certificates in 2013 in the Argentine Northeast, where the Jujuy Province is located, was similar to the one detected in this study in term newborns. Argentine records on the prevalence of those phenotypes refer to child populations over the age of 6 months calculated with the WHO standard.18 The National Nutrition and Health Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Nutrición y Salud) performed in Argentina in 2004–2005 establishes, for the population of Jujuy, regardless of the geographic altitude, 1.8% (95% CI 0.8–4.1), 9.5% (95% CI 5.3–16.6) and 0.6% (95% CI 0.3–1.4) prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting, respectively.18 A Latin American study19 compared IG-21 percentiles with newborn Peruvians born >3400m.a.s.l. and did not find significant differences with reference to the IG-21 standard, but underweight, stunting and wasting prevalence were not estimated.

The observed prevalences of newborn phenotypes were relatively low, especially for underweight and stunting, because they are also lower than the clinical significance cut-off points <10% and <20%, respectively, suggested by WHO.20 Stunting at birth seems to have a relatively low prevalence even in low-income settings, but it increases sharply with gestational age.21 Those results are somewhat similar to an earlier study9 of fetal growth impairment, which met strict individual eligibility criteria, where stunting affected 3.8% and wasting affected 3.4% of a low-risk population of newborns.

In a recent risk factor analysis for childhood stunting in developing countries, the worldwide leading risk factor was fetal growth restriction (FGR), defined as being at term and small for gestational age, which underlines the need for reliable indicators of fetal growth.22 Of the 12 conditions studied, advanced maternal age, BMI lower than 18.5kg/m2, hypertension, congenital malformations, and prematurity were more strongly associated with higher adjusted risk of underweight than to stunting or wasting at HA. Prevalence of tuberculosis is three times higher at altitude (53×10,000 newborns), and it was only associated with wasting, while nulliparity showed a similar risk for underweight and wasting. No statistically significant evidence of an independent association with any of the phenotypes studied was found for the remaining conditions.

At HA, congenital malformations were associated with duplication of risk of stunting (AOR: 2.62) and wasting (AOR: 2.52), but the risk was seven times higher for underweight (AOR: 7.66).

In the Jujuy Province, and using the same source, Grandi et al.23 demonstrated that the prevalence of prematurity, SGA, and fetal growth restriction shows an increasing relationship with geographic altitude, where the last two indicators – above 3500m.a.s.l. – may significantly duplicate the values found at sea level. In Northwestern Argentina, other studies came to the same conclusion,24 where an increase in prematurity due to an increase in altitude could even represent an adaptive advantage for preterm births under those conditions, as was found in the present study for wasting, with an adjusted risk reduction of almost 40%. Another explanation is that there are three possible alternatives for the presence of an insult that jeopardizes fetal growth under these conditions: gestational continuation, resulting in a newborn with fetal growth restriction; spontaneous or medically indicated interruption of pregnancy, with consequent premature birth; or fetal death.

That background would support the hypothesis that in altitude regions, and by an evolutionary mechanism, prematurity and fetal death may occur because of evident reductions in O2 tension above 2000m.a.s.l., suggesting a threshold effect beyond which small reductions in the provision of O2 may substantially reduce fetal oxygenation.25 This is sustained by a report of the Argentine Ministry of Health's Bureau of Health Statistics and Information (DEIS), informing that the contribution of premature fetuses (<37+0 weeks) to fetal mortality in Jujuy was 72% in 2013.

Geographic altitude and hypertension complications of pregnancy may independently reduce birth weight,26 a phenomenon found in Jujuy Province newborns above 2000m.a.s.l.12,15 and in the current study (Table 1).

Stunting constitutes a global indicator of child welfare, reflecting social inequalities and describing frequent specific results of the neonatal period (low birth weight, small for gestational age, prematurity, short for gestational age and small head circumference). For this reason, the assessment of this indicator in newborns has recently increased in importance in the perspective of the first 1000 days of life. Fetal stunting could be related to organic conditions (e.g. malformations) and is widely regarded as a cumulative, “long-term” process analogous to chronic undernutrition in children,27 that requires exposure to one or more risk factors for several months or throughout pregnancy. Alternatively, neonatal wasting is likely to reflect acute exposures in the weeks before delivery, with more rapid fat deposition.28 Other studies, however, suggest that differences in severity, rather than the timing and duration of the insults, result in distinct phenotypes of impaired fetal growth, with wasting representing the more severe cases.29 The fact that phenotype prevalence differs in terms of GA presentation and prevalence between preterm and term pregnancies suggests different risk factors (like diabetes, hypertension or preeclampsia at HA) and consequently, increased medically-indicated interruption of pregnancies to protect maternal and fetal well-being.

Most maternal factors considered in this study were weakly associated with or constitute a protective factor to phenotype differences due to altitude (particularly stunting). Therefore, those differences may probably be attributed to the stressing effect of altitude hypoxia interacting with other characteristics of these ecosystems not considered in this analysis (nutritional, socioeconomic, genetic, ethnic, sociodemographic, and geographic).10,11,30 The prenatal growth pattern of newborns in the Jujuy Province resembles the pattern found in altitude ecosystems in other ontogenetic stages. In fact, several studies of Jujuy Province children, adolescents and adults’ growth indicate that children are shorter and lighter than those living closest to sea level.10,13 However, since the impaired fetal growth found in the HA population is a complex syndrome, further characterization and validation of phenotypes in different populations is needed.

The main strengths of the study are the high representative sample of geographic altitude, the identification of risk factors of three phenotypes associated with fetal growth restriction knowingly associated with low birth weight, and the introduction of IG-21 as a robust epidemiological tool to be used in future studies.

LimitationsThe main limitation is the final sample – 61.2% of live newborns –, probably because only births registered in public facilities were included. Other limitations were incomplete information and GA estimated by the last menstrual date, as recommended by DEIS. On the other hand, models explained low altitudinal risks according to different phenotypes, since factors known to be associated with fetal growth (maternal smoking, use of illicit drugs, history of low birth weight and prematurity, social status, etc.) were not registered.

ConclusionsUnderweight, stunting, and wasting risks were higher at a high altitude, and were associated with recognized maternal and fetal conditions. Usage of those three phenotypes will help to prioritize preventive interventions and focus the management of fetal undernutrition.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martínez JI, Román EM, Alfaro EL, Grandi C, Dipierri JE. Geographic altitude and prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting in newborns with the INTERGROWTH-21st standard. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:366–73.