To investigate association between parental locus of control (belief of individuals about what or who has control of the events of their lives) and bottle feeding habits among children from 3 to 5 years of age.

MethodologyParental locus of control validated in Brazil, and semi-structured questionnaire to obtain sociodemographic, health, and oral habit behaviors was applied to mothers of 992 preschool children. Outcome variable “use of feeding bottle” was studied according to the time of its use (≤36 months and >36 months). Simple logistic regression models were adjusted and raw odds ratios were estimated for variables of distal blocks, which contemplated parental locus of control, socioeconomic characteristics of family, and maternal habits. In the intermediate block, the variables for conditions of the child's birth and place of health care attendance during the prenatal period and early childhood were included. In the proximal block, the time of breastfeeding and pacifier use were reported. Variables were analyzed from the distal to the proximal block, and the individual analyses that presented p≤0.20 remained in each model; included in the subsequent block were the variables with p≤0.10, because this was a study of prevention.

ResultsLonger time of feeding bottle use was associated with the internal parental locus of control, mothers older than 31 years of age, white race, premature children, who used pacifiers and are treated in the private health system.

ConclusionsChildren who maintained the habit of feeding bottle use for a longer time were those whose mother presented an internal locus of control.

The feeding bottle is still frequently used worldwide, in opposition to the recommendations of agencies such as the World Health Organization and Brazilian Ministry of Health, which recommend exclusive breastfeeding up to the sixth month of the child's life and avoiding substitutes for mother's milk and/or artificial nipples.1

The mother's choice of type and duration of feeding has a direct influence on the time of oral habits,2 among them the use of feeding bottles. This places children's health at risk, considering its interference in craniofacial development and in the functions of respiration, swallowing, phonation, and mastication.3

The mother's decision to offer her children feeding bottles may be influenced by a combination of individual and behavioral factors.3–5 Among the behavioral factors, the mother's suffering when the baby cries and the need to control infants’ behaviors may be cited.6 Thus, the use of the feeding bottle may be a way for the mother to gain control over the child's feeding, since it is possible to determine the times and quantities of that which is offered, and especially its quality, suiting the food to the child's taste or needs.

This being so, it is possible that mothers with greater tendency to assume control of day-to-day situations, whether for themselves or for their families, are those who most make us of this utensil for feeding their children. With the purpose of verifying this association, theories were investigated which would explain these behavioral patterns, and thus the locus of control, a theory developed by Rotter in 1966, was created. The locus of control refers to individuals’ beliefs about what or who has control of the events of their lives.7 It is said that individuals tend to present an external locus of control when they are used to attributing the events that occur in their lives to other people, the environment, destiny or chance. On the other hand, individuals with an internal locus of control are those who believe that occurrences depend on their own capacities and actions.7 In this sense, it is believed that applying the theory of the locus of control may contribute to an understanding of the reasons that lead to mothers to opt for the use of the feeding bottle.

To identify whether the locus of control is internal or external, various instruments have been developed, among them the Parental Locus of Control Scale in Health (PLOCH), which was adapted to the Brazilian culture by Cerqueira and Nascimento in 2008.8 With the use of this scale, the perception of external or internal control by parents was observed to be associated with the health of their children.8,9 However, the literature presents no studies that have verified the influence of control of parents regarding oral habits, more specifically, to the use of the feeding bottle. Thus, the objective this study was to investigate association between parental locus of control and the habit of bottle feeding among children from 3 to 5 years of age.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (CAEE 36894814.8.0000.5418), and informed consent was obtained from each of the participants.

Study participantsThe sample was composed of mothers of preschool children ranging from 3 years to 5 years and 11 months old, enrolled in school units of a mid-sized city in the interior of the state of São Paulo. In this research, no data from mothers of children with physical, sensory, and/or intellectual disabilities were included.

The sample was selected by the process of sampling by clusters, in two stages, by drawing 13 of the 33 school units existent in the city. After this, the children were drawn proportionally to the total number of children at each nursery school unit.

The sample size was calculated in order to provide a test power (1−β) of 0.80 with a level of significance of 0.05 for an odds ratio of 1.5, 50% of responses in the non-exposed group, and a level of precision of sampling (interval of confidence) of ±5%, with a level of confidence of 95%. Considering a design effect of 1.5 for the estimate of prevalence of deleterious oral habits and a possible loss of 20%, a sample totaling 992 participants was required. Thus, the sample was composed of 855 mothers and 137 fathers. According to Cerqueira and Nascimento,8 the locus of control refers to the perception of fathers and mothers, so that both could participate in the study.

Data collection instrumentsA self-applicable questionnaire was used to collect data relative to socioeconomic and demographic variables and those related to gestation and health behaviors.10 In addition, the PLOCH scales, adapted to and validated for the Brazilian population by Cerqueira and Nascimento,8 were applied.

PHLOC is composed of 18 questions related to the parents’ belief about whom or what controls the events related to the health of their children, which are distributed into three domains:

- -

Internality (I): evaluation of the degree to which the individual believes he/she controls his/her life.

- -

Other Powerful Persons (OP): evaluation of the belief that this control is in the hands of powerful persons.

- -

Chance/Luck (A) evaluation of the belief of being controlled by chance, luck, or destiny.

The PLOCH has five response options for each question, in a Likert-type scale, varying from “completely disagree” to “completely agree.” It was observed that the higher the score in each scale was, the greater was the belief that this was the factor that controlled the individual's life/health.11

Data analysisFor analysis of the data, the outcome considered was time of feeding bottle use less than or equal to 36 months, and longer than 36 months. The independent variables – age, mother's and father's educational level, monthly family income, number of persons in the family, and time of natural breastfeeding – were dichotomized by the median. The following variables were classified as “Yes” or “No”: mother smoked during gestation, smokers in the home, mother underwent prenatal care, prematurity, child's health problems, and use of pacifier. Parental locus of control was dichotomized as internal or external. External control included two subscales: OP and A.

The variables were grouped into three hierarchical blocks according to the theoretical model of Buccini et al., developed in 2014.12 This model establishes a prior order of importance among the pertinent and determinant factors for the event of interest. These factors may act in a distal (superior level), intermediate, and/or proximal (inferior level) manner. The groups were thus distributed as follows:

- a)

Block I: Distal. Factors related to socioeconomic characteristics and parental locus of control (internality or externality): parents’ marital status (married/partner, single/divorced/widowed), family income (≤3 minimum wages or >3 minimum wages), mother's schooling (up to complete high school or college), father's schooling (up to complete high school or college), mother's age (≤31 years or >31 years) and father's age (≤36 years or >36 years), order of birth of children (youngest sibling, oldest sibling, middle child, and twins), number of family members (≤4 or >4), mother smoked during gestation (yes or no), smokers in the house (yes or no), number of children (≤2 or >2).

- b)

Block II: Intermediate. Factors related to conditions of birth: type of delivery (normal or cesarean/forceps), prematurity (yes or no), child's gender (female or male), child's ethnic group (white/brown/black/indigenous/yellow). In the intermediate block, the characteristics related to health services were also included: mother underwent prenatal care (yes or no), doctor who provided prenatal care (public health system doctor (Brazilian national health service [SUS]) or doctors who worked in the private sector), child has a health problem (yes or no) and where the child was attended when it had health problems (public health system doctor [SUS] or doctors who worked in the private sector).

- c)

Block III: Proximal. Factors related to characteristics concerning the child's feeding and oral habits: time of breastfeeding (≤10 months or >10 months), use of pacifier (yes or no).

Simple logistic regression models were adjusted and the raw odds ratios were estimated with 95% confidence intervals for each variable of the distal, intermediate, and proximal blocks. After this, hierarchical multiple regression model was adjusted, according to the model of Buccini et al., developed in 2014.12 Initially, the models that presented p≤0.20 in the individual analyses were tested in blocks. The blocks were separately analyzed; first, the distal block, then the intermediate, and finally, the proximal, with only the variables with p≤0.10 remaining in the final model, and with this value being defined as the limit because this was a study of prevention, so that no important information would be lost. The data were analyzed using SAS software and adjustments of the models were evaluated by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and by the −2 log-likelihood statistic.

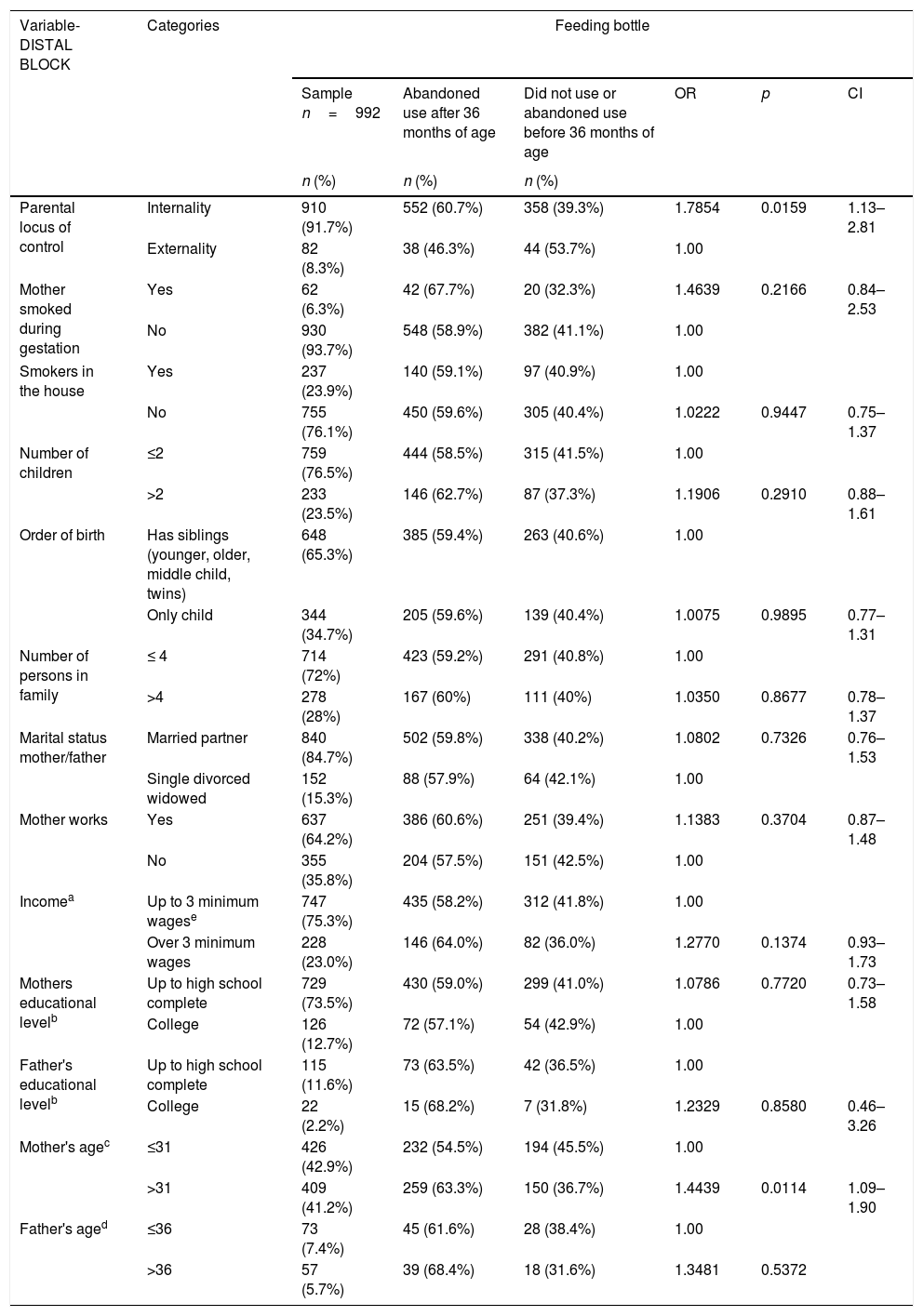

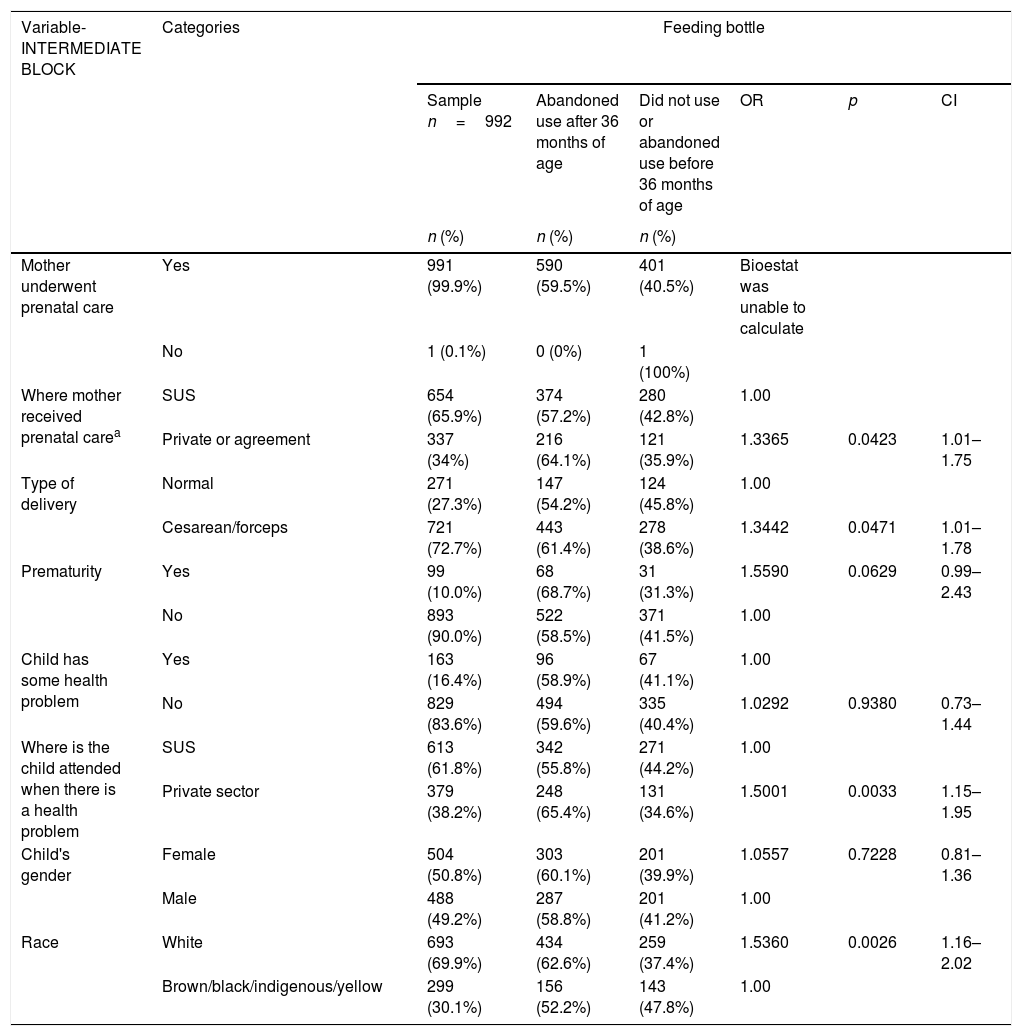

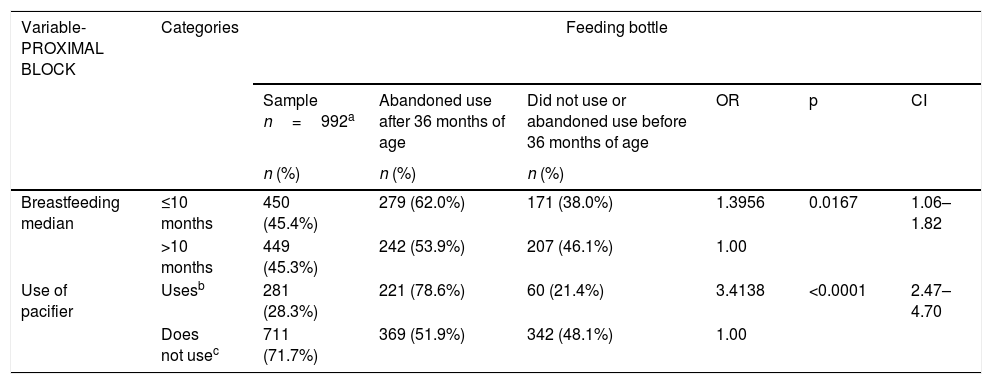

ResultsBy association analysis, in the distal block, the habit of bottle feeding for more than 36 months was associated with internal locus of parental control and mothers older than 31 years of age. While in the intermediate block, the association with longer bottle use time occurred with the following variables: mothers who received prenatal care in the private sector and those who had cesarean delivery, children born premature, those treated in the private health system for health problems, and white children. Breastfeeding less than ten months and use of pacifier were associated with longer time of use of bottle in the proximal block (p<0.10; Tables 1–3). Dichotomous variables number of children (total number of children in the family), number of people in the family (number of people living in the same environment as the child), and maternal age showed no association with the locus of control (p>0.05; Table 1).

Association between use of feeding bottle and socioeconomic, behavioral, and parental locus of control variables in preschool children of an age from 36 to 71 months (n=992).

| Variable-DISTAL BLOCK | Categories | Feeding bottle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample n=992 | Abandoned use after 36 months of age | Did not use or abandoned use before 36 months of age | OR | p | CI | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Parental locus of control | Internality | 910 (91.7%) | 552 (60.7%) | 358 (39.3%) | 1.7854 | 0.0159 | 1.13–2.81 |

| Externality | 82 (8.3%) | 38 (46.3%) | 44 (53.7%) | 1.00 | |||

| Mother smoked during gestation | Yes | 62 (6.3%) | 42 (67.7%) | 20 (32.3%) | 1.4639 | 0.2166 | 0.84–2.53 |

| No | 930 (93.7%) | 548 (58.9%) | 382 (41.1%) | 1.00 | |||

| Smokers in the house | Yes | 237 (23.9%) | 140 (59.1%) | 97 (40.9%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 755 (76.1%) | 450 (59.6%) | 305 (40.4%) | 1.0222 | 0.9447 | 0.75–1.37 | |

| Number of children | ≤2 | 759 (76.5%) | 444 (58.5%) | 315 (41.5%) | 1.00 | ||

| >2 | 233 (23.5%) | 146 (62.7%) | 87 (37.3%) | 1.1906 | 0.2910 | 0.88–1.61 | |

| Order of birth | Has siblings (younger, older, middle child, twins) | 648 (65.3%) | 385 (59.4%) | 263 (40.6%) | 1.00 | ||

| Only child | 344 (34.7%) | 205 (59.6%) | 139 (40.4%) | 1.0075 | 0.9895 | 0.77–1.31 | |

| Number of persons in family | ≤ 4 | 714 (72%) | 423 (59.2%) | 291 (40.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| >4 | 278 (28%) | 167 (60%) | 111 (40%) | 1.0350 | 0.8677 | 0.78–1.37 | |

| Marital status mother/father | Married partner | 840 (84.7%) | 502 (59.8%) | 338 (40.2%) | 1.0802 | 0.7326 | 0.76–1.53 |

| Single divorced widowed | 152 (15.3%) | 88 (57.9%) | 64 (42.1%) | 1.00 | |||

| Mother works | Yes | 637 (64.2%) | 386 (60.6%) | 251 (39.4%) | 1.1383 | 0.3704 | 0.87–1.48 |

| No | 355 (35.8%) | 204 (57.5%) | 151 (42.5%) | 1.00 | |||

| Incomea | Up to 3 minimum wagese | 747 (75.3%) | 435 (58.2%) | 312 (41.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| Over 3 minimum wages | 228 (23.0%) | 146 (64.0%) | 82 (36.0%) | 1.2770 | 0.1374 | 0.93–1.73 | |

| Mothers educational levelb | Up to high school complete | 729 (73.5%) | 430 (59.0%) | 299 (41.0%) | 1.0786 | 0.7720 | 0.73–1.58 |

| College | 126 (12.7%) | 72 (57.1%) | 54 (42.9%) | 1.00 | |||

| Father's educational levelb | Up to high school complete | 115 (11.6%) | 73 (63.5%) | 42 (36.5%) | 1.00 | ||

| College | 22 (2.2%) | 15 (68.2%) | 7 (31.8%) | 1.2329 | 0.8580 | 0.46–3.26 | |

| Mother's agec | ≤31 | 426 (42.9%) | 232 (54.5%) | 194 (45.5%) | 1.00 | ||

| >31 | 409 (41.2%) | 259 (63.3%) | 150 (36.7%) | 1.4439 | 0.0114 | 1.09–1.90 | |

| Father's aged | ≤36 | 73 (7.4%) | 45 (61.6%) | 28 (38.4%) | 1.00 | ||

| >36 | 57 (5.7%) | 39 (68.4%) | 18 (31.6%) | 1.3481 | 0.5372 | ||

OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Association between use of feeding bottle and socioeconomic, behavioral, and parental locus of control variables in preschool children of an age from 36 to 71 months (n=992).

| Variable-INTERMEDIATE BLOCK | Categories | Feeding bottle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample n=992 | Abandoned use after 36 months of age | Did not use or abandoned use before 36 months of age | OR | p | CI | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Mother underwent prenatal care | Yes | 991 (99.9%) | 590 (59.5%) | 401 (40.5%) | Bioestat was unable to calculate | ||

| No | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | ||||

| Where mother received prenatal carea | SUS | 654 (65.9%) | 374 (57.2%) | 280 (42.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| Private or agreement | 337 (34%) | 216 (64.1%) | 121 (35.9%) | 1.3365 | 0.0423 | 1.01–1.75 | |

| Type of delivery | Normal | 271 (27.3%) | 147 (54.2%) | 124 (45.8%) | 1.00 | ||

| Cesarean/forceps | 721 (72.7%) | 443 (61.4%) | 278 (38.6%) | 1.3442 | 0.0471 | 1.01–1.78 | |

| Prematurity | Yes | 99 (10.0%) | 68 (68.7%) | 31 (31.3%) | 1.5590 | 0.0629 | 0.99–2.43 |

| No | 893 (90.0%) | 522 (58.5%) | 371 (41.5%) | 1.00 | |||

| Child has some health problem | Yes | 163 (16.4%) | 96 (58.9%) | 67 (41.1%) | 1.00 | ||

| No | 829 (83.6%) | 494 (59.6%) | 335 (40.4%) | 1.0292 | 0.9380 | 0.73–1.44 | |

| Where is the child attended when there is a health problem | SUS | 613 (61.8%) | 342 (55.8%) | 271 (44.2%) | 1.00 | ||

| Private sector | 379 (38.2%) | 248 (65.4%) | 131 (34.6%) | 1.5001 | 0.0033 | 1.15–1.95 | |

| Child's gender | Female | 504 (50.8%) | 303 (60.1%) | 201 (39.9%) | 1.0557 | 0.7228 | 0.81–1.36 |

| Male | 488 (49.2%) | 287 (58.8%) | 201 (41.2%) | 1.00 | |||

| Race | White | 693 (69.9%) | 434 (62.6%) | 259 (37.4%) | 1.5360 | 0.0026 | 1.16–2.02 |

| Brown/black/indigenous/yellow | 299 (30.1%) | 156 (52.2%) | 143 (47.8%) | 1.00 | |||

OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

Association between use of feeding bottle and socioeconomic, behavioral, and parental locus of control variables in preschool children aged 36–71 months (n=992).

| Variable-PROXIMAL BLOCK | Categories | Feeding bottle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample n=992a | Abandoned use after 36 months of age | Did not use or abandoned use before 36 months of age | OR | p | CI | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Breastfeeding median | ≤10 months | 450 (45.4%) | 279 (62.0%) | 171 (38.0%) | 1.3956 | 0.0167 | 1.06–1.82 |

| >10 months | 449 (45.3%) | 242 (53.9%) | 207 (46.1%) | 1.00 | |||

| Use of pacifier | Usesb | 281 (28.3%) | 221 (78.6%) | 60 (21.4%) | 3.4138 | <0.0001 | 2.47–4.70 |

| Does not usec | 711 (71.7%) | 369 (51.9%) | 342 (48.1%) | 1.00 | |||

OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval.

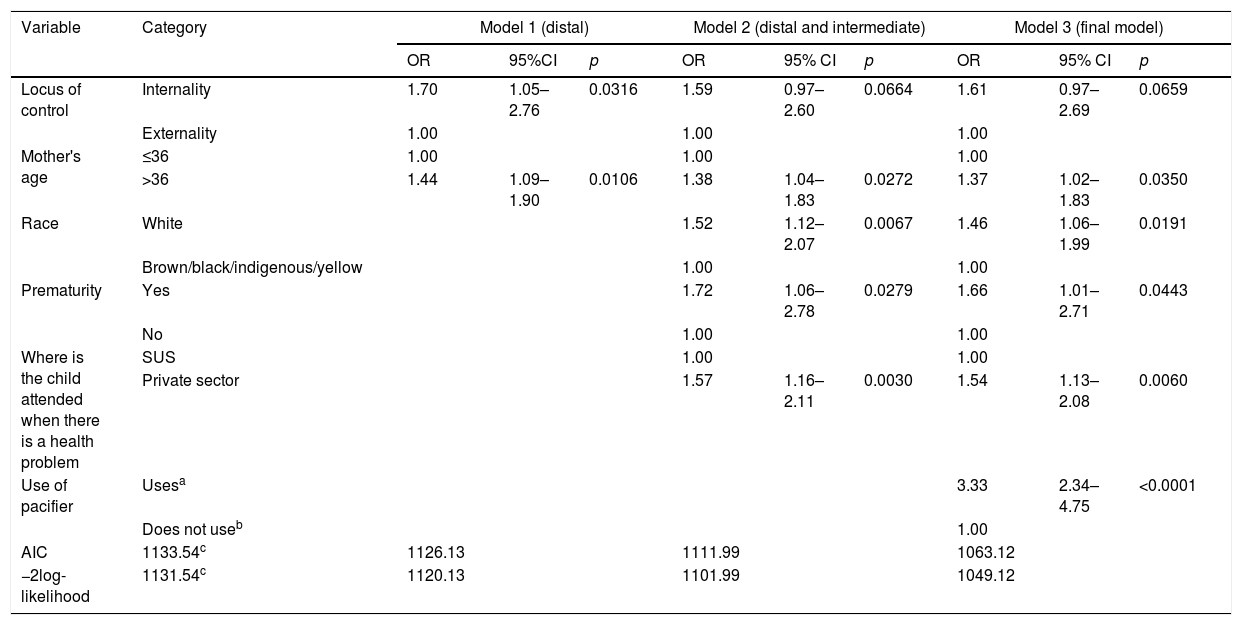

The hierarchical multiple logistic regression analyses revealed that longer time of feeding bottle use was associated with the internal parental locus of control, mothers older than 31 years of age, white children, premature birth, those who use or used pacifiers at some moment in their lives, and those treated in the private health system (Table 4).

Result of hierarchical multiple logistic regression for the outcome variable use of feeding bottle.

| Variable | Category | Model 1 (distal) | Model 2 (distal and intermediate) | Model 3 (final model) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Locus of control | Internality | 1.70 | 1.05–2.76 | 0.0316 | 1.59 | 0.97–2.60 | 0.0664 | 1.61 | 0.97–2.69 | 0.0659 |

| Externality | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Mother's age | ≤36 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| >36 | 1.44 | 1.09–1.90 | 0.0106 | 1.38 | 1.04–1.83 | 0.0272 | 1.37 | 1.02–1.83 | 0.0350 | |

| Race | White | 1.52 | 1.12–2.07 | 0.0067 | 1.46 | 1.06–1.99 | 0.0191 | |||

| Brown/black/indigenous/yellow | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Prematurity | Yes | 1.72 | 1.06–2.78 | 0.0279 | 1.66 | 1.01–2.71 | 0.0443 | |||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Where is the child attended when there is a health problem | SUS | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Private sector | 1.57 | 1.16–2.11 | 0.0030 | 1.54 | 1.13–2.08 | 0.0060 | ||||

| Use of pacifier | Usesa | 3.33 | 2.34–4.75 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Does not useb | 1.00 | |||||||||

| AIC | 1133.54c | 1126.13 | 1111.99 | 1063.12 | ||||||

| −2log-likelihood | 1131.54c | 1120.13 | 1101.99 | 1049.12 | ||||||

OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval; AIC, Akaike information criterion.

Due to the importance of psychological and behavioral factors that motivate mothers to use feeding bottles, this pioneering study investigated the association between parental locus of control and the habit of feeding bottle use among preschool children.

The literature has related that individuals with internal locus of control present more adequate health behaviors.7,13 Studies in the field of oral health7,13 have affirmed that mothers with internal locus of control had greater probability of having caries-free children, showing that when parents believed that the prevention of caries was their responsibility, more effective preventive practices were performed.

In this study, however, mothers with internal locus of control were more predisposed to offer their children feeding bottles; i.e., internality was associated with a habit that could be harmful to the child's health. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that people who demonstrate an internal locus of control are those who believe they control the events of their lives, and here, nutritional control of the child could be included. By offering the feeding bottle, mothers have greater control over the child's feeding, dosing frequency, quantity, and quality of the ingestion of milk and other liquid foods.

Natural feeding is associated with the free demand for providing the baby with milk, which limits the feeling of control by the mother, because it is not possible to measure the quantity of milk ingested every time the child breastfeeds, and possibly, due to the belief that mother's milk is “weak,” insufficient, and would not sustain the baby.6,14,15 In view of the foregoing, the decision-making process related to the infant's feeding has been verified to be influenced by the perception of maternal control in response to the infant's behavior, seeing that mothers express concern about the possibility of not producing sufficient milk, and the need to control the infant's behavior in order to avoid the child's crying and satisfying it as quickly as possible, and thus restore her sense of control.6

On the other hand, feeding with a formula from the feeding bottle may encourage the practice of a more controlled feeding routine,16 because the clues indicative of the child's hunger and satiety are clearer, and eventually, more evenly spaced.17

The mother's control is sensitive to the child's appetite and weight, since mothers who have the perception that their children are underweight and have less appetite increase food control,18,19 and provide higher food intake using a bottle to stimulate consumption, causing overeating and weight gain children.18–20

In this sense, the feeding bottle provides mothers with greater control over feeding, because the mothers decide how much milk to put into the feeding bottle, and provides more information about how much the child consumed due to the visual signs (particularly in transparent feeding bottles), indicated on the bottle, instead of being guided by the infant's self-regulated ingestion.20,21

Moreover, children who should already be receiving food equal to that of adults frequently show themselves to be without appetite, but accept receiving milk from the feeding bottle. Therefore, the mothers’ desire for control of the routine could lead to the choice of children's food.22

Corroborating the data of the present study, one study23 verified that mothers older than 30 years also had the habit of offering their children feeding bottles, probably due to their greater involvement with a professional career or a personal decision in not wishing to breastfeed.23 However, some studies12,14 have verified that adolescent mothers also showed a short period of exclusive breastfeeding. In these cases, the reasons for using the feeding bottle were associated with family influence in offering the babies liquids right from the first days of life.

Another finding of the present study was the longer time that mothers of premature babies used the feeding bottle. Premature babies generally have difficulty with sucking at the breast, due to the immaturity of muscles for suction and swallowing.24 In this sense, concern about the vulnerability of the health and weight of their children may trigger actions of food compensation by parents to encourage the ingestion of foods, favoring the prolonged permanence of the feeding bottle in early childhood.25

Moreover, longer time of feeding bottle use has also been associated with pacifier use. The pacifier and feeding bottle habits are commonly cited in the literature as factors that may have a great influence on interrupting breastfeeding.4,12 This fact may be explained by the confusion that the nipples of the pacifier and feeding bottle generate in the baby, and may be caused by the differences in the pattern of suction existent between the breast and artificial nipple. This difference may interfere in the baby's capacity for sucking at the mother's breast, leading to rejection of the breast and preference for the feeding bottle.14,26–28

Furthermore, in the present study, children of white ethnicity continued to use a feeding bottle for a longer period of time. Previous studies have confirmed that variables such as ethnicity may play an important role in the use of the feeding bottle in the infant population.27 There are indications that parents of children of white ethnicity were more predisposed than those of black ethnicity to offer their children feeding bottles.28 However, there is no consensus about this in the literature.27

This study also showed that children attended to in the private service were more predisposed to use the feeding bottle for a longer time. This may be understood because the public health service in Brazil develops actions for the promotion of infant health that cover the time from the gestational period (with encouragement of breastfeeding)29 up to 9 years of age,30 which is not a pattern observed when parents seek the private services.

A relevant aspect of the present study was the use of multilevel analysis, which allowed the confounding variables of the study to be controlled.23 Such an analysis is more appropriate for research with hierarchical data, functioning to explain how the individual variables and the demographic and socioeconomic contexts of families are capable of influencing the situation studied.23 In the case of the present study, the influence of the parent's locus of control on the longer time of feeding bottle use was studied.

Regarding the limitations of the study, as it is a retrospective study, parents may not remember, precisely, the age at which habits or breastfeeding were interrupted.

Identifying the association of parental locus of control and prolonged use of the feeding bottle may contribute to the planning of strategies by health professionals, with a view to preventing the onset of the habit in infant feeding, or of interrupting it as early as possible, specifically among the group of mothers older than 31 years, with children of white ethnicity, born premature, who use pacifiers and are attended to in the private health system, with the purpose of avoiding the harmful effects associated with feeding bottle use.

Longer time of feeding bottle use was associated with the internal parental locus of control, mothers older than 31 years of age, white ethnicity, premature children, and those who used pacifiers and are treated in the private health system.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.