The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the practical diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to eosinophilic esophagitis and to increase the visibility of the disease among pediatricians.

SourcesA search of the MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL databases and recent consensus statements and guidelines were performed.

Summary of the findingsThe definition of eosinophilic esophagitis is based on symptoms and histology. It is important to rule out other diseases associated with esophageal eosinophil-predominant inflammation. It is not yet clear whether the increased prevalence is due to a real increase in incidence or a result of increased awareness of the disease. Various options for management have been used in pediatric patients, including proton pump inhibitors, dietary restriction therapies, swallowed topical steroids, and endoscopic dilations. More recently, proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis have been contemplated on the same spectrum, and proton pump inhibitors should be considered the initial step in the treatment of these patients.

ConclusionsEosinophilic esophagitis is a relatively new disease with a remarkable progression of its incidence and prevalence in the past two to three decades, and diagnostic criteria that are constantly evolving. It is important to better understand the pathogenesis of the disease, the predisposing factors, the natural history, and the categorization of varying phenotypes to develop diagnostic and therapeutic strategies that meet the clinical needs of patients.

Fornecer uma visão geral do diagnóstico e do tratamento da esofagite eosinofílica na prática clínica e aumentar a visibilidade da doença entre os pediatras.

Fontes dos dadosFoi feita uma busca na literatura relevante nos bancos de dados Medline, Embase, CINAHL e consensos e diretrizes recentes foram revisados.

Síntese dos dadosA definição de esofagite eosinofílica é baseada nos sintomas e na histologia. É importante excluir outras doenças associadas com inflamação esofágica predominantemente eosinofílica. Ainda não está claro se o aumento na prevalência é devido a um real aumento da incidência ou se é o resultado da maior suspeição diagnóstica. Várias opções para tratamento, inclusive inibidores de bomba de prótons, restrições dietéticas, esteroides tópicos deglutidos e dilatações endoscópicas têm sido usadas em pacientes pediátricos. Mais recentemente a eosinofilia esofágica responsiva a inibidores de bomba de prótons e a esofagite eosinofílica têm sido contempladas no mesmo espectro e os inibidores de bomba de prótons devem ser considerados como opção inicial no tratamento desses pacientes.

ConclusõesA esofagite eosinofílica é uma doença relativamente nova com uma notável progressão da incidência e prevalência nas últimas 2-3 décadas e critérios diagnósticos estão em evolução constante. É importante entender melhor a patogênese dessa doença, os fatores predisponentes, a história natural e a categorização dos diferentes fenótipos para desenvolver estratégias diagnósticas e terapêuticas que vão ao encontro das necessidades clínicas dos pacientes.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is defined as a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated, inflammatory esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.1,2

The definition of EoE is based on two diagnostic pillars: symptoms and histology. It is important to rule out other diseases associated with esophageal eosinophil-predominant inflammation, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal Crohn's disease, achalasia, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, connective tissue disorders, and esophageal infections before EoE can be diagnosed.1–3

Since its first recognition as a distinct disorder approximately 23 years ago, there has been an increase in the prevalence of EoE in many parts of the world recently and a growing number of studies on EoE have been published, including consensus documents and clinical practice guidelines.1–7

While initially described in North America and Europe, EoE is a global phenomenon and has recently been reported in other regions, including South and Central America, Africa, and Asia.8–10

It is yet not clear whether the increased prevalence is due to a real increase in incidence or a result of increased awareness of the disease.8,11–14 Several studies have attempted to define the extent of EoE by estimating its epidemiology in different populations. Different methodological approaches have been employed, ranging from population-based research to studies defining the frequency of EoE in various series of endoscopies and esophageal biopsies. The results of epidemiological studies with varied methodology have shown a gradual increase in the prevalence of EoE in recent years, with a recent estimate of four patients per 100000 population.15 Because diagnosis is frequently deferred due to delayed request for medical care by patients with esophageal symptoms, poor recognition of typical endoscopic appearances of EoE and failed recognition or recording of typical histologic findings in biopsies, these numbers likely underestimate the true prevalence of the disease. Nevertheless, EoE has recently been considered a common cause of chronic or recurrent esophageal symptoms in children and also represents the most prevalent cause of dysphagia among adolescents and young adults worldwide.1–3

Various options for managing EoE, including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), dietary restriction therapies, swallowed topical steroids, and endoscopic dilations for esophageal strictures have been used in pediatric and adult patients. Recent publications including systematic reviews and meta-analyses support the use of these modalities of treatment.1–4,8 As EoE is a chronic progressive disorder, a long-term maintenance treatment is typically required.

The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the practical diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to EoE and to increase the visibility of the disease among pediatricians and other health-care professionals.

EoE and proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE)The initial diagnostic criteria of EoE were based on the concept that gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and EoE were mutually exclusive disorders2,3 and consensus guidelines required unresponsiveness to PPI to confirm the diagnosis of EoE.1,4 However, the correlation between GERD and EoE appears to be more complex, because both diseases may respond to treatment with PPIs.1,4

It is intriguing to ponder why an immune-mediated disease would respond to an acid-blocking medication. Multiple studies have reported patients with GERD-like symptoms and significant esophageal eosinophilia that responded to PPI treatment.7,16–22 This may in part be explained by the anti-inflammatory effects of PPIs unrelated to acid suppression, with inhibition of Th2 cytokines and eotaxin-3 production as demonstrated in recent studies.21–24 This mechanism, along with improvement of barrier function, make PPIs an effective form of treatment for some EoE cases.25

It is difficult to predict whether a patient with esophageal eosinophilia will respond to a PPI. In fact, the clinical, endoscopic, and histological phenotypes of PPI responders and non-responders and the results of their esophageal pH monitoring have been shown to be indistinguishable.17,18,20–22 These findings prompted the creation of a new term: PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE). This denomination was used to define a group of patients with typical symptoms of EoE, esophageal eosinophilic infiltration, and a clinical and histological response to PPI.18,20,26–28

A prospective study conducted in 2011 showed that 50% of adult patients with suspected EoE responded to treatment with PPIs and that there were overlapping clinical, endoscopic, and histological characteristics among responders and non-responders.16 This study revealed that 20% of patients did not respond to PPI, even those with abnormal pH monitoring (suggestive of GERD), while 33% of patients with normal pH monitoring were PPI responders.16

Overall, in adults as well as in children, excluding the individual case series, histologic response rates to PPIs ranged from 23 to 83%, and clinical response rates were 23 to 82%.7 These findings suggest that some patients with PPI-REE may in fact have EoE.1,17,20

In 2016, Gutiérrez-Junquera et al.18 published a prospective series with 56 children and adolescents with suspected EoE, evaluating their response to systematic PPI therapy. Almost 70% of these children responded clinically and histologically to PPI therapy. Twenty-four children (47%) presented complete symptomatic remission. Neither clinical, endoscopic, or histological characteristics, nor pH monitoring results were capable of predicting the response to PPI therapy. This was the first prospective series in children demonstrating that, in comparison to adult studies, up to 50% of pediatric patients may achieve clinical and histological remission on PPI therapy. Fourteen children were followed for 12 months with lower doses of PPIs, and clinical and histological sustained response was achieved in 11 of them (78.6%).18 Moreover, the same investigators had very recent preliminary data demonstrating that most PPI-responsive EoE children (70.1%) remain in histological and clinical remission on lower dose maintenance treatment at the 1-year follow-up, with an adequate safety profile.29 Complete histological response to 8 weeks of the PPI trial was associated with higher probability of ongoing histological response.29

Molina-Infante et al.,20 in a review article, suggested that the term PPI-REE is an inappropriate disease descriptor based on a response to a single drug and should therefore be disregarded. According to these authors, patients with PPI responsiveness perhaps should be considered within the same spectrum of EoE. This group is phenotypically indistinguishable from similar patients who do not respond to PPIs.1,17,20

These findings and others provide evidence that patients with PPI-REE exhibit significant overlap with EoE and that these patients represent a continuum of the same pathogenic allergic mechanisms that underlie EoE.17,20 Further supporting this concept is the finding that PPI therapy can reverse gene expression associated with PPI-REE to that associated with classical EoE.30 Taken together, these findings provide new insights into potential disease etiology and management strategies for patients with significant esophageal eosinophilia and the elimination of the term PPI-REE.1,17,20

In accordance with the EoE guidelines, published in 2017, the authors suggest that PPI-REE and EoE are on the same spectrum and that PPIs should be considered the first step in the treatment of patients with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and esophageal eosinophilia.1

EoE diagnostic criteria are constantly evolving.1,7,17,20 New evidence shows that the correlation between esophageal eosinophilic infiltration and GERD is becoming more and more complex.20

Pediatricians have often taken the lead in conducting EoE studies with topical steroids26,31–33 and various dietary treatments,34–36 but there is a lack of well-conducted studies evaluating the rate of response to PPI therapy in children with EoE.

Diagnosis of EoEEoE is conceptually defined in the 2011 guideline as a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated esophageal disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-predominant inflammation.2 Clinically significant esophageal eosinophilia is defined as ≥15 eos/hpf in the most involved area.

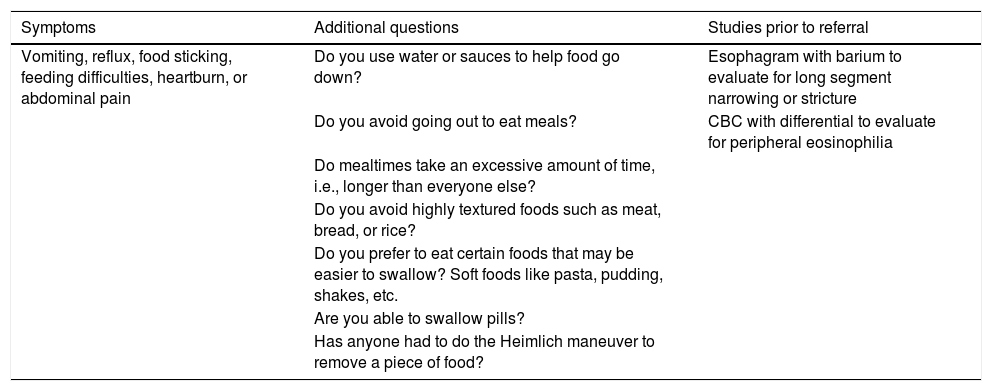

In order to try to identify patients who may have EoE in practice, a more detailed history should be obtained if symptoms such as vomiting, reflux, food sticking, feeding difficulties, heartburn, or abdominal pain are identified. In addition, if these are seen in a child who has a history of atopic disease or a family history of food impaction, esophageal dilation/stretching, or eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, a higher index of suspicion should be entertained (Table 1).

Additional questions and possible studies in order to identify patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

| Symptoms | Additional questions | Studies prior to referral |

|---|---|---|

| Vomiting, reflux, food sticking, feeding difficulties, heartburn, or abdominal pain | Do you use water or sauces to help food go down? | Esophagram with barium to evaluate for long segment narrowing or stricture |

| Do you avoid going out to eat meals? | CBC with differential to evaluate for peripheral eosinophilia | |

| Do mealtimes take an excessive amount of time, i.e., longer than everyone else? | ||

| Do you avoid highly textured foods such as meat, bread, or rice? | ||

| Do you prefer to eat certain foods that may be easier to swallow? Soft foods like pasta, pudding, shakes, etc. | ||

| Are you able to swallow pills? | ||

| Has anyone had to do the Heimlich maneuver to remove a piece of food? |

At times, when symptoms in children consist of only chronic gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, which are not uncommon in children, it is challenging for the pediatrician to discern EoE from GERD. In addition to looking for history of concurrent atopy and/or IgE-mediated food allergy, assessing for failure to thrive is very helpful, as this indicates a potentially more serious disease than GERD, including EoE. In fact, failure to thrive can occur in up to one-third of children with EoE and is potentially reversible with successful therapy for EoE.

The endoscopist must carefully evaluate for endoscopic signs of EoE (esophageal rings, longitudinal furrows, exudates, edema, strictures, or narrow caliber esophagus) and ideally report the findings using the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS).37 Esophageal biopsy specimens should be obtained in all cases where EoE is a clinical possibility (even when the endoscopic appearance is normal).37,38

Since EoE tends to be patchy, multiple biopsies from two or more esophageal levels targeting areas of apparent inflammation are recommended, as this will increase the diagnostic yield. Gastric and duodenal biopsies should be obtained in order to exclude other gastrointestinal eosinophilic disorders (eosinophilic gastritis, duodenitis, or gastroenteritis).1–3

At this stage, a patient would be considered to have suspected EoE if there are symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and at least 15 eos/hpf on biopsy. These patients should also be evaluated for non-EoE disorders that cause or potentially contribute to esophageal eosinophilia. GERD, hypereosinophilic syndrome, non-EoE EGIDs, Crohn's disease, infections, connective tissue disorders, and drug hypersensitivity reactions have been associated with esophageal eosinophilia but are uncommon or are present with clinical features that readily distinguish them from EoE.2,10 In some patients, it may be difficult to ascertain the precise contribution of GERD to esophageal eosinophilia and the clinical evaluation for GERD could be undertaken prior to a definitive diagnosis of EoE.17,39

EoE is finally diagnosed and defined as “confirmed EoE” when there are symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, at least 15 eos/hpf (or ∼60 eos/mm2) on esophageal biopsy, in patients with no other causes of symptoms and/or esophageal eosinophilia.1–3

Clinical treatmentsThe current clinical treatment of EoE includes the three Ds: drugs, diet and, dilations.

PPIsPPIs are considered by many to be the first option to treat patients with esophageal eosinophilia and esophageal symptoms.40

In general, the recommended dose is 1mg/kg twice daily up to a maximum adult dose for at least 8–12 weeks.18 After this period, repeat endoscopy is recommended to verify if there is persistence of esophageal eosinophils. If there are more than 15 eos/hpf and symptoms after PPI treatment, diet or steroids are recommended.

If there are less than 15 eosinophils/hpf, it may be possible to reduce the dose and maintain PPIs only once daily. If the patient is clinically stable and has no symptoms, follow-up endoscopy may be performed in 6–12 months. A prospective study in a pediatric cohort demonstrated that patients responding to PPIs (78%) remained in clinicopathologic remission at the 1-year follow-up on maintenance PPI therapy.18 The first long-term follow-up study in 75 adult PPI-REE patients showed that all subjects who discontinued therapy had symptomatic and/or histologic relapse.19 Most patients who relapsed attained histologic remission after dose escalation, which suggests that some patients responding to PPIs might require long-term high-dose therapy.

There are so far no studies on the long-term (more than 1 year) outcomes of PPI treatment for EoE. Thus, patients treated with PPIs should be carefully monitored.

CorticosteroidsSystemic corticosteroids induce clinical and histological response. However, due to their side-effect profile, they are not recommended for treatment of EoE.1,2,40,41

Swallowed topical corticosteroids including fluticasone and viscous budesonide have been shown to provide good clinical and histological response.30–32,41–43

Budesonide can be administered as an oral viscous slurry (1mg daily for children under the age of 10 years, and 2mg daily for older children and adults). Viscous budesonide can be prepared by mixing with sucralose (1g packet per 1mg of budesonide).33 The dose of topical fluticasone in children can range from 88 to 440mcg/day in divided doses, while the dose in adults can range from 880 to 1760mcg/day in divided doses.26,41

Patients must avoid ingestion of foods and liquids for at least 30min after taking the medication.

The efficacy of topical corticosteroids in treating EoE, as assessed in several trials and summarized in meta-analyses, indicates that budesonide and fluticasone propionate are significantly superior to placebo, both in decreasing esophageal eosinophil mucosal infiltration and in relieving symptoms.44

A meta-analysis showed that topical corticosteroids seem to be effective in inducing histological remission, but may not have a similar significant impact in improving clinical symptoms of EoE.45

Other drugsOther drugs with a better long-term safety profile have been tested in treating EoE.

Montelukast, a selective leukotriene receptor antagonist, has been evaluated as a therapeutic option, but recent studies have shown that this agent is not effective in reducing esophageal eosinophilic infiltration.46,47

The use of biologic therapies including mepolizumab and reslizumab, two anti-IL-5 antibodies, has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing esophageal and blood eosinophils, but without significant reduction in symptoms.48–50 The use of the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab was shown to improve symptoms in two open-label studies.51,52 As patients were kept on conventional therapies for EoE, the improvement could be a result of a placebo effect.51

Given the increased esophageal epithelial cell TNF-α expression in EoE, infliximab, an anti-TNF-α antibody, was studied in patients with EoE, with lack of success both clinically and histologically.53

None of the biologicals studied in EoE have been highly effective, though many demonstrated some histological benefit, especially those that target the Th2 axis. The future for biologicals is promising, however, as the pathophysiology of EoE is better understood, clinical assessment tools are validated, patient subsets that respond best to biologicals are identified, and dosages of biologicals are optimized.53

DietsThere are currently three options for dietary management of EoE.

The first is an elemental diet, consisting of complete elimination of all food allergens and instead consuming an amino acid-based formula for 6–8 weeks. In the event of disease remission, this would be followed by reintroduction of single foods or food groups to identify food culprits. The great majority of patients (>90%) show good clinical and histological response with the elemental diet.34,54,55 The rapid resolution of symptoms with an elemental diet is very encouraging. However, poor palatability, high costs, and the need for large volumes of formula are potential obstacles for this treatment modality. In some patients, the use a nasogastric tube for the administration of the formula may be necessary.55

Another dietary treatment option is a test-directed elimination diet, which consists of using the information from allergy tests (food-specific IgE, skin prick test, and/or atopy patch test) to guide the diet. Only foods identified as potentially allergenic are excluded from the diet.34 Histologic remission has been achieved in 48% of children and 32% of adult patients with this approach.54,56,57

The empiric dietary elimination of the four (milk, wheat, soy, and egg) or six (milk, wheat, soy, egg, nuts, seafood) common allergenic foods has been shown to be effective.56–58 Histologic remission rates of 73% in children and 71% in adults have been reported with the six-food elimination diet (SFED).57 Studies with the four-food elimination diet have reported remission rates of 64% in children and 54% in adults.50–52

The use of single-food elimination diet (cow's milk elimination) has demonstrated encouraging results by some investigators, but further prospective studies are needed to assess the effectiveness of this approach.59

These alternatives may be more easily accepted than elemental diets and compliance is higher. The choice of dietary management should be discussed with the patient or family, to consider factors that may influence treatment adherence (e.g., age, financial resources, feeding difficulties, psychological impact on dietary restrictions, etc.).60

Endoscopic dilationEndoscopic dilation with through-the-scope balloons or wire-guided bougies is a safe and effective procedure for the management of esophageal strictures in patients with EoE. A high complication rate was reported in small case series continuing until 2006, but recent studies have demonstrated a low risk of perforations (<1%) when the usual precautions are taken, including slow and gradual dilatation.61,62 Concomitant medical treatment (PPIs, steroids, diet) is recommended to reduce the chance of stricture recurrence by treating the underlying esophageal inflammation.62

Future directionsEoE is a relatively new disease with a remarkable progression of the incidence and prevalence in the past two to three decades.

It is important to better understand the molecular pathogenesis of EoE, the predisposing environmental and individual factors for some patients to develop the disease, the natural history and the categorization of varying phenotypes, and their association with genotypes.

Since EoE accounts for significant health-related costs,63 it will be critical to assess the best diagnostic criteria, the least invasive diagnostic modality for assessment of disease activity, and the best treatment strategies, with an emphasis on the development of new easy and inexpensive therapeutic approaches. Collaboration among health-care professionals and researchers is crucial to meet the clinical needs of patients.

Conflicts of interestC.T.F. is a lecturer, developed scientific and educational and/or support material in research projects for Danone, FQM. M.C.V. is a lecturer, developed scientific and educational and/or support material in research projects for Danone, Nestlé Nutrition Institute and Aché Laboratories. G.T.F. is the founder of EnteroTrack and a consultant for Shire, Copyrights - UpToDate. M. C. is a consultant for Actelion, Shire, Allakos; and the recipient of research funding from - Nutricia, Shire, Regeneron. F.C.B. declares no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferreira CT, Vieira MC, Furuta GT, Barros FC, Chehade M. Eosinophilic esophagitis—Where are we today? J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:275–81.

Study carried out at Departamento de Pediatria of the Universidade Federal de Porto Alegre and the Hospital Pediátrico Santo Antônio, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.