In this article, the authors aimed to review the different tools used in the monitoring of enthesitis-related arthritis.

SourcesThe authors performed a literature review on PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases. The dataset included the original research and the reviews including patients with enthesitis-related arthritis or juvenile spondylarthritis up to October 2020.

Summary of findingEnthesitis-related arthritis is a category of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. It is characterized by the presence of enthesitis, peripheral arthritis, as well as axial involvement. The only validated tool for disease activity measurement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the Disease Activity Score: It has proven its reliability and sensitivity. Nevertheless, due to an absence of validated evaluation tools, the extent of functional impairment, as well as the children and parents’ perception of the disease, could not be objectively perceived. Despite the great progress in the field of imaging modalities, the role they play in the evaluation of disease activity is still controversial. This is partially due to the lack of validated scoring systems.

ConclusionsFurther work is still required to standardize the monitoring strategy and validate the outcome measures in enthesitis-related arthritis.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) represents a group of diverse inflammatory disorders affecting children before the age of 16.1 The diagnosis is made after ruling out other categories of arthritis. The International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) recognizes 7 subgroups.2 Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) is one of the main subgroups.3 ERA represents 20% of all JIA patients. According to ILAR criteria, ERA is defined either by the association of both arthritis and enthesitis, or only one, with at least 2 of the following items: Sacroiliac joint tenderness, inflammatory back pain, HLA-B27 positivity, family history of HLA-B27–associated diseases, uveitis, or onset in a male aged 6 years or older.4

There are similar features between the adult form of spondyloarthritis (SpA) and JIA.5 SpA is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the axial skeleton, entheses, and peripheral joints. While adult-onset is associated with more frequent axial symptoms, juvenile-onset is associated with a higher prevalence of arthritis and enthesitis.6 The ASAS criteria of SpA take into account imaging results, markers of inflammation, and clinical response to NSAIDS treatment.7 Unlike SpA, the ERA criteria are mostly based on clinical history. Several assessment tools have been developed for SpA. Nevertheless, specific recommendations for the monitoring of patients with ERA in clinical practice are still lacking. While previous studies have attempted to extrapolate the adult tools of disease activity, functional assessment, and treatment response to the pediatric population, a specific approach is still lacking. Therefore, it is required to have a specific scoring system for JIA, taking into consideration its specific clinical and radiologic aspects.

In this article, the authors aimed to provide an updated review regarding the existing assessment tools in ERA. The authors also highlighted the importance of considering this pediatric form as a separate entity, with its own specific clinical features and prognosis.

Research strategyThe authors of the present study performed a literature review on PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases using the following set of keywords: (i) “enthesitis-related arthritis, "OR “juvenile spondyloarthritis, "OR” juvenile idiopathic arthritis,” and (ii) “tools,” OR “monitoring,” OR “imaging tools,” OR assessment”. The dataset included the original research and the reviews including patients with enthesitis-related arthritis or juvenile spondylarthritis up to October 2020. The authors also carried a cross-referenced research incorporating all studies and collected the resulting articles. Those not in English, French, or with no translation were excluded.

Disease activity assessmentAs in other inflammatory diseases, the anamnesis is still considered the best parameter for evaluating the disease activity and monitoring. Certainly, clinical evaluation is relevant in symptom assessment such as back pain, morning stiffness, and nocturnal waking.

Laboratory evaluation through tests of inflammatory activity (ESR and CRP) are also requested throughout the follow-up of each patient.

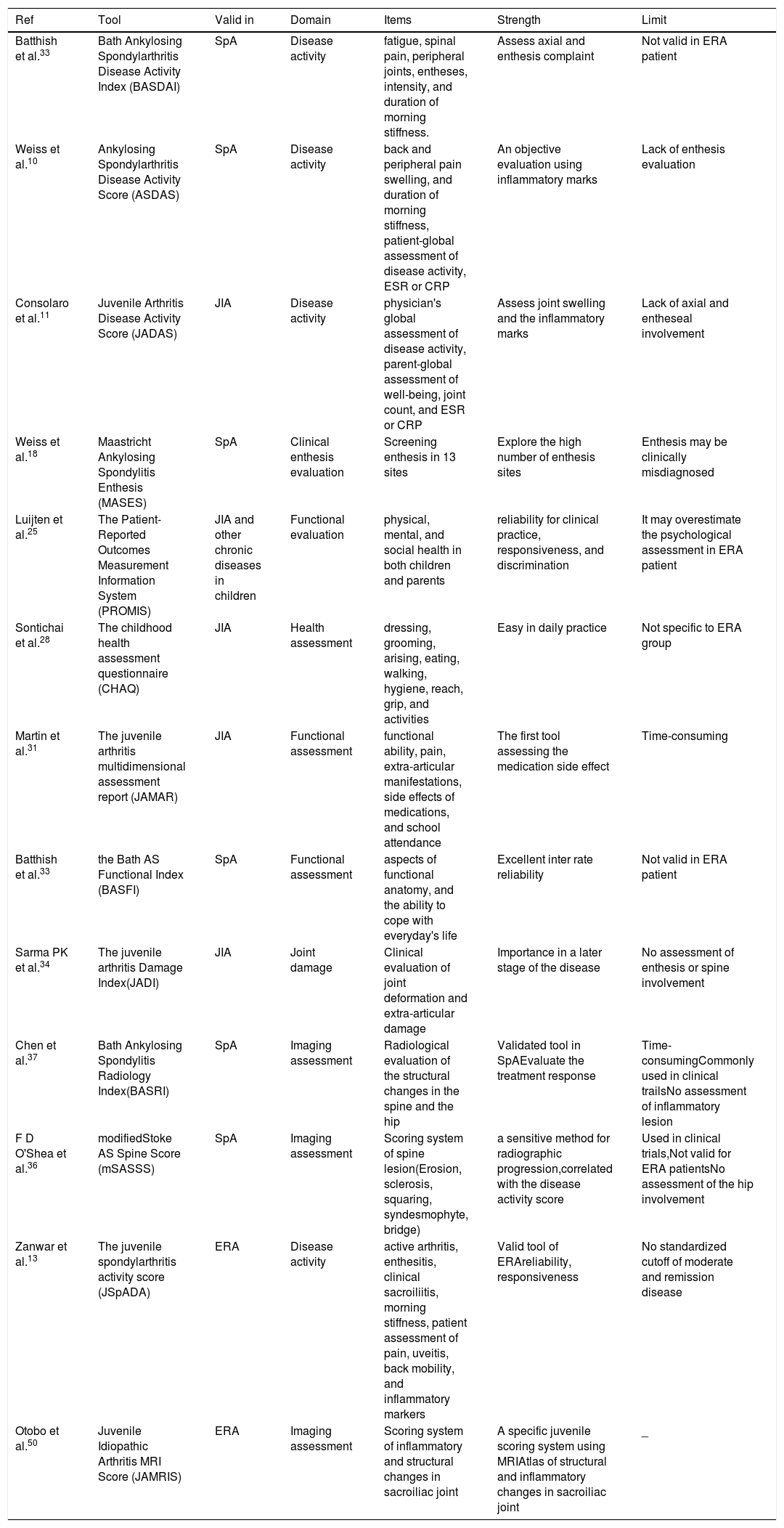

Thus, to integrate all these measurements into a single number, several composite scores were developed, allowing an additional advantage in disease monitoring. The Table 1 summarized the specific and generic tools used in ERA.

Generic and specific instruments used in ERA.

| Ref | Tool | Valid in | Domain | Items | Strength | Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batthish et al.33 | Bath Ankylosing Spondylarthritis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) | SpA | Disease activity | fatigue, spinal pain, peripheral joints, entheses, intensity, and duration of morning stiffness. | Assess axial and enthesis complaint | Not valid in ERA patient |

| Weiss et al.10 | Ankylosing Spondylarthritis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) | SpA | Disease activity | back and peripheral pain swelling, and duration of morning stiffness, patient-global assessment of disease activity, ESR or CRP | An objective evaluation using inflammatory marks | Lack of enthesis evaluation |

| Consolaro et al.11 | Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (JADAS) | JIA | Disease activity | physician's global assessment of disease activity, parent-global assessment of well-being, joint count, and ESR or CRP | Assess joint swelling and the inflammatory marks | Lack of axial and entheseal involvement |

| Weiss et al.18 | Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis (MASES) | SpA | Clinical enthesis evaluation | Screening enthesis in 13 sites | Explore the high number of enthesis sites | Enthesis may be clinically misdiagnosed |

| Luijten et al.25 | The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) | JIA and other chronic diseases in children | Functional evaluation | physical, mental, and social health in both children and parents | reliability for clinical practice, responsiveness, and discrimination | It may overestimate the psychological assessment in ERA patient |

| Sontichai et al.28 | The childhood health assessment questionnaire (CHAQ) | JIA | Health assessment | dressing, grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities | Easy in daily practice | Not specific to ERA group |

| Martin et al.31 | The juvenile arthritis multidimensional assessment report (JAMAR) | JIA | Functional assessment | functional ability, pain, extra-articular manifestations, side effects of medications, and school attendance | The first tool assessing the medication side effect | Time-consuming |

| Batthish et al.33 | the Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI) | SpA | Functional assessment | aspects of functional anatomy, and the ability to cope with everyday's life | Excellent inter rate reliability | Not valid in ERA patient |

| Sarma PK et al.34 | The juvenile arthritis Damage Index(JADI) | JIA | Joint damage | Clinical evaluation of joint deformation and extra-articular damage | Importance in a later stage of the disease | No assessment of enthesis or spine involvement |

| Chen et al.37 | Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Radiology Index(BASRI) | SpA | Imaging assessment | Radiological evaluation of the structural changes in the spine and the hip | Validated tool in SpAEvaluate the treatment response | Time-consumingCommonly used in clinical trailsNo assessment of inflammatory lesion |

| F D O'Shea et al.36 | modifiedStoke AS Spine Score (mSASSS) | SpA | Imaging assessment | Scoring system of spine lesion(Erosion, sclerosis, squaring, syndesmophyte, bridge) | a sensitive method for radiographic progression,correlated with the disease activity score | Used in clinical trials,Not valid for ERA patientsNo assessment of the hip involvement |

| Zanwar et al.13 | The juvenile spondylarthritis activity score (JSpADA) | ERA | Disease activity | active arthritis, enthesitis, clinical sacroiliitis, morning stiffness, patient assessment of pain, uveitis, back mobility, and inflammatory markers | Valid tool of ERAreliability, responsiveness | No standardized cutoff of moderate and remission disease |

| Otobo et al.50 | Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis MRI Score (JAMRIS) | ERA | Imaging assessment | Scoring system of inflammatory and structural changes in sacroiliac joint | A specific juvenile scoring system using MRIAtlas of structural and inflammatory changes in sacroiliac joint | _ |

JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; CRP, C reactive protein; ERA, enthesitis-related arthritis; ESR, erythrocytes sedimentation rate; SpA, spondylarthritis.

The use of BASDAI or ASDAS is recommended by the American college of rheumatology for the adult SpA patients monitoring.8 However, given the silent axial involvement and the predominant peripheral arthritis in ERA patients, BASDAI and ASDAS are not well suited for the pediatric population.9,10

The juvenile arthritis disease activity score (JADAS) has excellent reliability and validity in the polyarticular and oligoarticular forms of JIA.11 However, it is not well studied in the ERA form. Despite having good measurement properties, JADAS does not assess the spinal involvement or the presence of enthesitis.

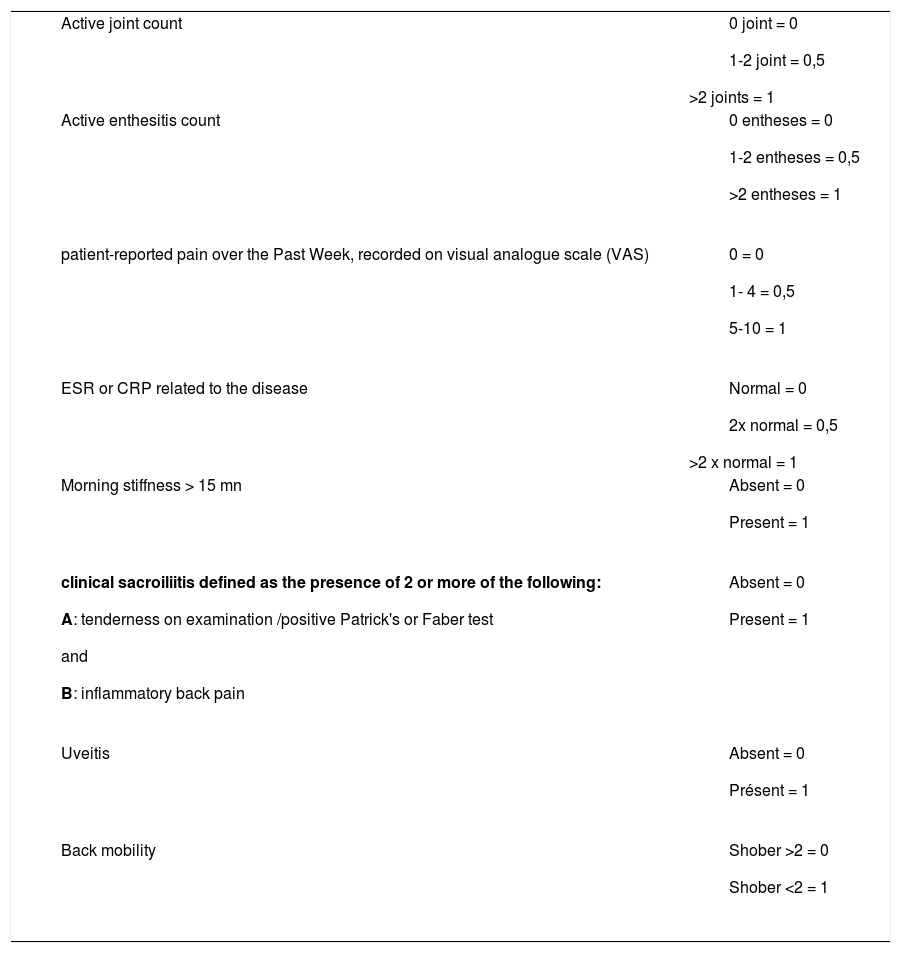

The Juvenile spondyloarthritis disease activity (JSpADA) stands out for being specifically designed for this patient group.12 It is the first disease activity assessment tool developed and prospectively validated for the pediatric population.13 JSpADA includes the measuring of eight items: active arthritis, enthesitis, clinical sacroiliitis, morning stiffness, patient assessment of pain, uveitis, back mobility, and inflammatory markers (Table 2).

Juvenile spondylarthritis disease activity.

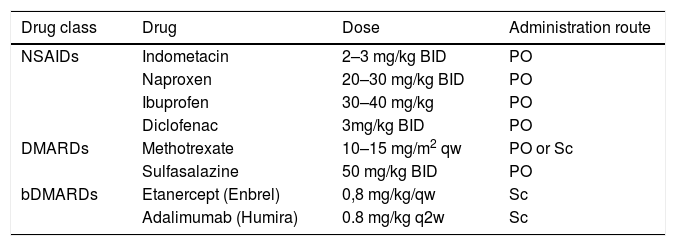

Therapeutic option in enthesitis related arthritis.

bDMARDs, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; BID, twice per day; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; mg, milligram; kg, kilogram; Sc, subcutaneous; qw, once per week; q2w, once per every 2 weeks.

The first item of this tool consists of active arthritis count, as assessed by clinical exam. A maximum of 10 joints is established. However, the score does not specify which joint to examine routinely.

The second item is the evaluation of enthesitis. Enthesitis is defined by the presence of inflammation at sites where the ligaments, tendons, or joint capsules are attached to the bone.14 Tenderness upon direct palpation of the bones entheses insertions defines active enthesitis. Only ten sites were validated in JSpADA score, even though the number of active enthesitis very often exceeds this limit. Furthermore, the entheseal sites of screening weren't defined. Typically, the most affected sites in ERA are: the inferior pole of the patella, the insertions of the quadriceps, and the plantar fascia.15

Different scoring systems were used in clinical trials such as Leeds score, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis (MASES), and Major indices.6

The clinical detection of enthesitis may be misdiagnosed in children by the presence of apophysitis, injuries, and fibromyalgia.16 Therefore, ultrasound (US) appears useful for identifying inflammatory and structural lesions. Multiple studies have compared the US to the clinical exam, concluding that with the latter, the sensitivity of detecting enthesitis is low (22%), and the specificity is moderate (80%).14,15,17 Other studies showed that in children with ERA and normal clinical exams, ultrasonography displayed abnormalities in nearly half of the cases.18,19

The third item of JSpADA consisted of the measurement of the patient-reported spinal and peripheral joints level of pain, over the past week. A visual analog numeric rating scale is used for this purpose. However, disease activity seemed to be overestimated by the impact of fatigue and functional impairment, which can significantly influence children's well-being.20 Unlike JADAS, in JSpADA parent and physician evaluations of pain were not considered.

Inflammatory markers were also included in JSpADA, the same as for ASDAS measurement in adult SpA. They procured a more objective evaluation.5

JSpADA also included spinal involvement. In opposition to the adult form, in which inflammatory back pain is an important feature of the disease, in the juvenile form, spinal involvement appears later on. In addition, the definition of inflammatory back pain is not yet validated in the pediatric population; therefore, the JSpADA recommends the use of Calin criteria in evaluating back pain.

Clinical assessment of the sacroiliac joints was also included in JSpADA, but it continues to stir controversy. Only 30% of children with ERA have sacroiliac-joint involvement. Besides, sacroiliitis may be missing in the early stages of the disease. Its clinical assessment is also judged difficult due to the lack of objective symptoms. In a recent study, two-thirds of the children who presented with active sacroiliitis on MRI did not have tenderness upon clinical exam.21 However, in another study, the negative sacroiliac joint test had a significantly negative predictive value for MRI findings, suggesting that clinical evaluation could be sufficient.1

Another particular characteristic of JSpADA is the inclusion of extra-articular manifestations. Given its prognostic value, the evaluation of ocular complications is considered in JSpADA. However, the screening for uveitis is not always achievable upon routine clinical examinations.

JSpADA score also evaluates back mobility in the ERA group. Restriction of the lumbar spine is defined by a Schöber test of less than 2 cm. In a recent Indian study, the evaluation of the Schöber test was limited by the presence of active lower limb arthritis.13

To sum up, the JSpADA index has many strengths such as reliability, responsiveness, as well as significant correlations with other disease activity scores applied in SpA.22 However, despite being a practical score that can often be used in clinical practice, JSpADA has a moderate correlation with the functional index. More data are still required to standardize the index level and its therapeutic impact.

Functional assessment in ERAThere are a wide variety of tools to monitor the functional impact of JIA.20 These tools focus on the parents' and children's perception of the disease outcomes, as well as functional impairment, psychosocial and educational impact.23 The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a valid tool, evaluating the different aspects of physical, mental, and social health in both children and parents. The PROMIS item has been proven to be a valid and reliable tool in clinical practice to evaluate children with JIA. It also has a high discriminative potential for disease activity.24,25 The use of PROMIS for the estimation of physical impairment is not specific to JIA and could be applied to other chronic diseases in children. However, its use in ERA may be majored by the presence of depression or discomfort.26–28

The childhood health assessment questionnaire (CHAQ) is widely used in daily practice. CHAQ assesses eight areas of life: dressing, grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities. It is well correlated with disease activity in JIA.29 Even though CHAQ can discriminate between healthy subjects and JIA patients, it is not specific to the different subgroups. Furthermore, a higher CHAQ index at disease onset in the ERA group predicts reduced physical function and poor health status upon follow-up.30 Pain may lead to reduced physical activity in JIA patients, this is partially explained by the false perception of exercising playing a role in increasing joint damage and pain.31

The juvenile arthritis multidimensional assessment report (JAMAR) is a validated and reliable tool widely used in JIA.32 Through its 15 items, JAMAR aims to assess functional ability, pain, articular, and extra-articular manifestations, as well as the side effects of medications and school attendance.18

It is not, however, specific to the ERA form. It does not explore the impact of axial involvement and enthesitis. Besides, JAMAR lacks the assessment of the hip joint, which is an important factor influencing joint motion and activities. Therefore, it should have a crucial consideration in functional assessment.

BASFI seems to be the most relevant score in ERA and has shown good reliability in this group.33 It offers insight into pain, morning stiffness, and hip mobility.34 The children's VAS scales could be, however, falsely portrayed.20

These findings emphasize the need for specific functional scores including items from CHAQ, JAMAR, and BASFI.

Damage assessmentStructural joint damage could be assessed through clinical and imaging tools. The juvenile arthritis Damage Index (JADI) assesses articular and extra-articular damage using a short questionnaire and physical examination without the necessity for radiologic evaluation.35 JADI gives an idea about the extent of deformation and destruction of joints, without performing any imaging exams. However, the lack of assessment of enthesitis and spinal involvement limits its use in ERA patients. In addition to that, it has been established that there is a low association between spinal limitation and JADI.

In adult patients with SpA, ASAS recommends repeating radiographs every two years. However, the pace of imaging surveillance the pediatric population with ERA is still not codified.35

To assess the progression of radiographic spinal damage in the pediatric population, the Bath AS Radiological Index (BASRI) and the modified Stoke AS Spine Score (mSASSS) are proposed.36 However, they are both not specific to ERA patients.37,38

Hip involvement in the JIA population is frequent and is considered an important prognostic factor. Therefore, appropriate monitoring of this joint is required. Monitoring is achieved using specific scores that were specially developed for JIA, and therefore can be used with ERA patients.39

Among these scores are the Radiographic Score of the Hip40 and recently, the new radiographic score,41 which details space narrowing, growth abnormalities, erosion, and misalignment.

Currently, the purpose of treatment of all inflammatory disorders, especially those occurring in children, is to prevent joint damage. This justifies the significant need for imaging to assess disease progression. In this perspective, several international groups have been working on the validation of imaging modalities in the diagnosis and monitoring of JIA.42 While some of these studies addressed all available imaging modalities, others focused mainly on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the US.

The US has the advantage of assessing joint and periarticular inflammation, as well as detecting small bone erosions, that are not spotted by standard radiographs. It is considered a useful tool for the monitoring of peripheral arthritis and enthesitis in JIA, especially in ERA.

However, US findings in pediatric patients remain challenging given the frequency of US abnormalities in healthy children. This is partially explained by the physiological changes during growth.43,44

Recently, OMERACT ultrasound Task Force–Pediatric Group has validated the definition of US elementary lesions in JIA.42 However, no uniform grading score of active synovitis or enthesitis, in neither B-mode or Doppler US is available.43,45

Few studies have extrapolated the OMERACT definition to children.46 Synovitis was graded in Gray score, whereas, active enthesitis was described as tendon hypoechogenicity or thickening with increased vascularity.18

Currently, the childhood arthritis and rheumatology research alliance (CARRA) has developed the first US scoring system of the knee joint. Work is still in progress regarding other joints.47

MRI is the modality of choice for the diagnosis of ERA and could be the key tool to monitoring disease activity and guiding therapy decisions.48 Whole-body MRI was proposed as an objective tool for assessing children with ERA. But its high cost and extended examination time have limited its use. Another hitch of this modality is the lack of specificity of bone marrow edema in children. Bone marrow edema can be seen in healthy children due to a residual hematopoietic marrow.49 In 2018, The OMERACT group defined the consensual outcome measures of sacroiliac changes, named JAMRIS set.50 The proposed MRI protocol attempted to extrapolate the adult MRI definition to juvenile patients.22 However, the JAMRIS item did not allow the use of contrast in MRI sequences to detect inflammatory changes. Furthermore, it was required that MRI should systematically assess the hips, in addition to the sacroiliac joints.43

In conclusion, although several imaging tools are studied in children, most of them are conducted in JIA patients without taking into consideration the heterogeneity of the different subgroups, particularly the ERA.

Treatment response (Table 3)An accurate definition of inactive disease is crucial for monitoring ERA patients. However, remission is still not properly defined in this group. The American College of Rheumatology has, however, defined inactive disease in the polyarticular, oligoarticular, and systematic subgroups of JIA. The remission was defined by the absence of swollen joints and extra-articular signs, normal inflammatory markers, and the best physical assessment.51 These criteria did not include enthesitis and axial disability.

Weiß A and al.52 proposed a definition to remission for ERA patients as the presence of six of the following items: physician's global assessment of disease activity score of 0, no peripheral arthritis, no uveitis or enthesitis, morning stiffness < 15 mn, no inflammatory Bowel diseases and either ESR ≤ 20 mm/h or C reactive protein level ≤ 5 mg/L. In this series, only 23% of the patients were in remission without medication after 4 years of follow-up.

So far, no study has applied the recently proposed JSpADA clinically inactive disease cut-offs. Even though JSpADA identifies patients with high disease activity, patients with moderate, low disease activity and those at remission, need to be identified as well, by proper cut-offs.

ConclusionsThus far, there is no standardized monitoring strategy for ERA patients. In general, every clinical visit should assess spinal involvement, peripheral joints, entheses as well as extra-articular manifestations. The development of JSpADA presents an important milestone, as it is the first specific tool developed for ERA patients. It represents a further step into considering this disease as an independent form of JIA. The required rhythm of imaging control has not been yet established. Currently, it depends strongly on the disease activity. Ongoing studies nowadays highlight the challenges of the interpretation of abnormal imaging results in children, as well as the need for a validated MRI score system in ERA patients. Finally, a future effort is mandatory to establish standardized and recognized remission criteria. The presence of such criteria might improve the management strategy in ERA patients, as well as the prognosis of the disease.