This large study with a long-term follow-up aimed to evaluate the clinical presentation, laboratory findings, histological profile, treatments, and outcomes of children and adolescents with autoimmune hepatitis.

MethodsThe medical records of 828 children and adolescents with autoimmune hepatitis were reviewed. A questionnaire was used to collect anonymous data on clinical presentation, biochemical and histological findings, and treatments.

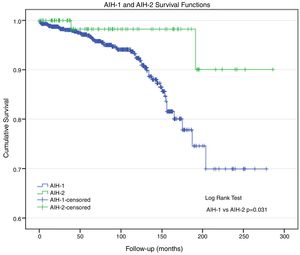

ResultsOf all patients, 89.6% had autoimmune hepatitis-1 and 10.4% had autoimmune hepatitis-2. The female sex was predominant in both groups. The median age at symptom onset was 111.5 (6; 210) and 53.5 (8; 165) months in the patients with autoimmune hepatitis 1 and autoimmune hepatitis-2, respectively. Acute clinical onset was observed in 56.1% and 58.8% and insidious symptoms in 43.9% and 41.2% of the patients with autoimmune hepatitis-1 and autoimmune hepatitis-2, respectively. The risk of hepatic failure was 1.6-fold higher for autoimmune hepatitis-2. Fulminant hepatic failure occurred in 3.6% and 10.6% of the patients with autoimmune hepatitis-1 and autoimmune hepatitis-2, respectively; the risk was 3.1-fold higher for autoimmune hepatitis-2. The gamma globulin and immunoglobulin G levels were significantly higher in autoimmune hepatitis-1, while the immunoglobulin A and C3 levels were lower in autoimmune hepatitis-2. Cirrhosis was observed in 22.4% of the patients; biochemical remission was achieved in 76.2%. The actuarial survival rate was 93.0%. A total of 4.6% underwent liver transplantation, and 6.9% died (autoimmune hepatitis-1: 7.5%; autoimmune hepatitis-2: 2.4%).

ConclusionsIn this large clinical series of Brazilian children and adolescents, autoimmune hepatitis-1 was more frequent, and patients with autoimmune hepatitis-2 exhibited higher disease remission rates with earlier response to treatment. Patients with autoimmune hepatitis-1 had a higher risk of death.

Este estudo com acompanhamento de longo prazo visou avaliar o quadro clínico, os achados laboratoriais, o perfil histológico, os tratamentos e os resultados de crianças e adolescentes com hepatite autoimune.

MétodosForam analisados os prontuários médicos de 828 crianças e adolescentes com HAI. Foi usado um questionário para coletar os dados anônimos sobre o quadro clínico, os achados bioquímicos e histológicos e os tratamentos.

ResultadosDe todos os pacientes, 89,6% tinham hepatite autoimune-1 e 10,4% hepatite autoimune-2. O sexo feminino foi predominante nos dois grupos. A idade média no início dos sintomas foi 111,5 (6; 210) e 53,5 (8; 165) meses nos pacientes com hepatite autoimune-1 e hepatite autoimune-2, respectivamente. Foi observado início clínico agudo em 56,1% e 58,8% e sintomas insidiosos em 43,9% e 41,2% dos pacientes com hepatite autoimune -1 e hepatite autoimune-2, respectivamente. A probabilidade de insuficiência hepática foi 1,6 vezes maior para hepatite autoimune-2; 3,6% e 10,6% dos pacientes com hepatite autoimune-1 e hepatite autoimune-2, respectivamente, apresentaram insuficiência hepática fulminante; o risco foi 3,1 vezes maior para hepatite autoimune-2. Os níveis de gamaglobulina e imunoglobulina G foram significativamente maiores nos pacientes com hepatite autoimune-1, ao passo que os níveis de imunoglobulina A e C3 foram menores em pacientes com hepatite autoimune-2; 22,4% dos pacientes apresentaram cirrose e a remissão bioquímica foi atingida em 76,2%. A taxa de sobrevida atuarial foi de 93,0%. Um total de 4,6% pacientes foram submetidos a transplante de fígado e 6,9% morreram (hepatite autoimune-1: 7,5%; hepatite autoimune-2: 2,4%).

ConclusõesNesta grande série clínica de crianças e adolescentes brasileiros, a hepatite autoimune-1 foi mais frequente e os pacientes com hepatite autoimune-2 mostraram maiores taxas de remissão da doença com respostas mais rápidas aos tratamentos. Os pacientes com hepatite autoimune-1 apresentaram maior risco de óbito.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease that is typically progressive and histologically characterized by periportal inflammation, bridging necrosis, liver cell rosetting, and marked plasma cell infiltration. Although the etiology is unknown, its pathogenesis is based at least partly on aberrant autoreactivity. The classical phenotype has been characterized by certain serological markers, especially antinuclear antibodies, smooth muscle antibodies (SMAs), and antibodies to liver kidney microsome type 1 (anti-LKM1s), regardless of the association with anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibodies, hypergammaglobulinemia, increased serum immunoglobulin (Ig)G levels, interface hepatitis on histological examination, and corticosteroid therapy responsiveness.1–3

Studies on the epidemiology and natural history of pediatric AIH have been published,4,5 which is important given that much of the knowledge on AIH is derived from studies on adults. The limited studies on children demonstrated the peculiarities of this disease in pediatric patients. The authors aimed to evaluate the clinical presentation, laboratory findings, histological profile, treatments, and outcomes of children and adolescents with AIH in South America in a large study with a long-term follow-up.

MethodsThis retrospective multicenter study was conducted to assess the clinical outcomes of 828 children and adolescents with a well-documented long-term AIH course according to the modified AIH International Study Group criteria.1 Data were collected from reports of single centers. A questionnaire assessed anonymous data on demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, biochemical and histological findings, and treatments. The patients were followed-up from 1983 to 2015 in 17 pediatric gastroenterology/hepatology centers throughout Brazil. This study was approved by the ethical committees of the institutions (CAAE No. 53562116.5.1001.0068).

All children and adolescents were submitted to a clinical and laboratory protocol, including assessment of biochemical parameters, such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), albumin, gamma globulin, international normalized ratio (INR), total and direct-reacting bilirubin (DB), serum glucose, triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid stimulating hormone measured using radioimmunoassay. Serum Ig and complement levels were measured using nephelometry, which were expressed in g/L and varied by center. The results were recorded as normal, increased, or decreased.

All patients were screened at presentation for anti-nuclear, anti-SMA, anti-LKM1, and anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Serum samples were titered up to 1/320. Titers of >1:40 and 1/20 were considered positive for anti-SMA and anti-LKM1, respectively. Additionally, the patients had negative findings for hepatitis A, B, and C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus. They had no history of drug or alcohol use or exposure to hepatotoxic drugs. Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson's disease were excluded.

Cholangiography was performed either via magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or via endoscopy in patients who did not respond to immunosuppressive drugs or had increased GGTP levels during disease monitoring.

Liver biopsy was performed in 664 (80.2%) patients before the immunosuppressive treatment via percutaneous needle biopsy using a Tru-Cut needle or surgery. A total of 253 children underwent more than one biopsy during follow-up to document relapses or as a criterion for therapy cessation after two years in cases of clinical and biochemical remissions. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were inspected via hematoxylin-eosin, periodic acid-Schiff after diastase digestion, reticulin silver impregnation, and Masson staining in all cases. Histological features were recorded in accordance with staging using a semi-quantitative four-point scoring system (i.e., absent, minimal, moderate, and severe). The parameters included architectural changes; portal and periportal infiltrates; liver cell damage and necrosis, such as focal (spotty) lytic necrosis and periportal or periseptal interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis); confluent necrosis; bridging necrosis; and submassive necrosis.6 Other features, such as bile duct injury and ductular reaction, were also evaluated.

Immunosuppressive therapy included a combination of prednisone (1–1.5mg/kg/day, maximum of 60mg/day) and azathioprine (1–1.5mg/kg/day). Prednisone monotherapy was performed whenever severe thrombocytopenia was present. Prednisone dose was reduced at each visit until a maintenance dose of 2.5–5mg was achieved, while maintaining stable clinical and laboratory parameters. Complete response and relapse were both defined in accordance with the modified AIH International Study Group criteria.1

Statistical analysisSPSS v. 24 (SPSS – Chicago, IL, United States) was used for the statistical analysis. All data are summarized in Tables 1–3. Normal data distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In order to verify the existence of associations between the groups and all categorical variables, logistic regression was used with the logit link function. Odds ratios were estimated, and the respective 95% confidence intervals were presented. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the two AIH types in relation to the quantitative variables. The significance level was set at p≤0.05. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as median (minimal; maximal) values.

Demographic and clinical data of AIH-1 and AIH-2 patients.

| Parameters | AIH-1 | AIH-2 | ORAIH-1/AIH-2(95% CI);logistic regression | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (months) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 111.5 (6; 210) | 53.5 (8; 165) | <0.001a | |

| Age at diagnosis (months) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 122.5 (6; 219) | 68.0 (12; 200) | <0.001a | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 186 (25.1%) | 13 (15.1%) | 1.88 (1.02, 3.47) | 0.044b |

| Female, n (%) | 556 (74.9%) | 73 (84.9%) | 1 | |

| Clinical presentation | ||||

| Acute, n (%) | 410 (56.1%) | 50 (58.8%) | 1.11 (0.71, 1.76) | 0.630b |

| Insidious, n (%) | 321 (43.9%) | 35 (41.2%) | 1 | |

| Fulminant | 0.005b | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 27 (3.6%) | 9 (10.6%) | 0.32 (0.14, 0.70) | |

| No, n (%) | 715 (96.4) | 76 (89.4) | 1 | |

| Hepatic failure | ||||

| INR>1.5, n (%) | 226 (30.7) | 31 (40.3) | 0.060b | |

| Extrahepatic manifestations | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 183 (24.8) | 12 (14.1) | 2.01 (1.07, 3.77) | 0.031b |

| No, n (%) | 555 (75.2) | 73 (85.9) | 1 | |

| Family history of autoimmune disease | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 161 (21.9%) | 18 (21.2%) | 1.42 (0.60, 1.80) | 0.883b |

| No, n (%) | 575 (78.1%) | 67 (78.7) | 1 | |

| AIH score (1999) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 17 (7; 28) | 15.5 (3; 123) | 0.001a | |

| Score (2008) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 7 (2; 10) | 6 (3; 9) | 0.001a | |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; min, minimum; max, maximum.

Complementary diagnostic test findings of the patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2.

| Parameters | AIH-1 | AIH-2 | ORAIH-1/AIH-2(95% CI);Logistic regression | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST (× UNL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 18 (0; 169) | 13 (0.7; 153) | 0.315a | |

| ALT (× UNL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 13 (0; 156) | 12.5 (0.8; 88) | 0.521a | |

| GGTP (× UNL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 3 (0; 37) | 3 (0; 17) | 0.368a | |

| ALP (× UNL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 1.3 (0; 47.7) | 1.5 (0; 6.5) | 0.365a | |

| TB (mg/dL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 3.2 (0; 32.1) | 3.9 (0.3; 66.2) | 0.334b | |

| DB (mg/dL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 2.1 (0; 24) | 1.8 (0.1; 37.4) | 0.794a | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 3.4 (0; 33) | 3.6 (1.3; 5) | 0.030a | |

| Gammaglobulin (g/dL) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 3.4 (0; 75) | 2.2 (0.8; 6.2) | <0.001a | |

| IgA – low, n (%) | 12 (3.3) | 13 (29.5) | 0.10 (0.04; 0.24) | <0.001b |

| IgM – high, n (%) | 131 (37.4) | 18 (40.9) | 0.88 (0.46; 1.66) | 0.685b |

| IgG – high, n (%) | 331 (83.6) | 34 (63) | 2.89 (1.55; 5.38) | 0.001b |

| C3 – low, n (%) | 83 (29.0) | 20 (46.5) | 0.49 (0.251; 0.94) | 0.032b |

| C4 – low, n (%) | 151 (53.9) | 20 (46.5) | 1.39 (0.73; 2.65) | 0.317b |

| Cholangiography (sclerosing cholangitis), n (%) | 58 (19.9) | 2 (11.8) | 1.59 (0.34; 7.40) | 0.551b |

| Portal inflammation (moderate-severe) | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 559 (93.9) | 61 (88.4) | 2.04 (0.91; 4.58) | 0.085b |

| No, n (%) | 36 (6.1) | 8 (11.6) | 1 | |

| Interface hepatitis | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 485 (83.3) | 52 (77.6) | 1.44 (0.78; 2.67) | 0.243b |

| No, n (%) | 112 (17.3) | 15 (22.4) | 1 | |

| Rosettes | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 310 (52.9) | 24 (35.3) | 2.06 (1.22; 3.47) | 0.007b |

| No, n (%) | 276 (47.1) | 44 (64.7) | 1 | |

| Plasma cells | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 315 (53.5) | 21 (30.4) | 2.63 (1.54; 4.50) | <0.001b |

| No, n (%) | 274 (46.5) | 48 (69.6) | 1 | |

| Fibrosis/cirrhosis | ||||

| Fibrosis, n (%) | 461 (77.9) | 52 (77.6) | 0.87 (0.49; 1.55) | 0.636b |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 131 (22.1) | 17 (24.6) | 1 | |

| Bile duct injury | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 56 (9.4) | 5 (7.5) | 1.29 (0.50; 3.34) | 0.602b |

| No, n (%) | 539 (90.6) | 62 (92.5) | 1 | |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; min, minimum; max, maximum.

Response to treatment and outcomes in AIH-1 and AIH-2 patients.

| Parameters | AIH-1N (%) | AIH-2N (%) | OR AIH-1/AIH-2 (95% CI); logistic regression | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remission | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 543 (74.7) | 76 (89.4) | 0.35 (0.17; 0.71) | 0.003b |

| No, n (%) | 184 (25.3) | 9 (10.6) | 1 | |

| Time to remission (months) | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 7 (0; 250) | 4 (1; 149) | 0.002a | |

| Relapse numbers | ||||

| Median (min; max) | 3 (0; 13) | 3 (0; 6) | 0.433a | |

| Treatment discontinuation | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 49 (7.0) | 8 (10.0) | 0.68 (0.31; 1.48) | 0.328b |

| No, n (%) | 653 (93.0) | 72 (90.0) | 1 | |

| LTx | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 35 (4.7) | 3 (3.5) | 1.36 (0.41; 4.53) | 0.613b |

| No, n (%) | 702 (95.3) | 82 (96.5) | 1 | |

| Death | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 55 (7.5) | 2 (2.4) | 3.36 (0.80; 14.02) | 0.047b |

| No, n (%) | 680 (92.5) | 83 (97.6) | 1 | |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; LTx, liver transplantation; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Of the 828 patients, 742 (89.6%) had AIH-1 and 86 (10.4%) had AIH-2.

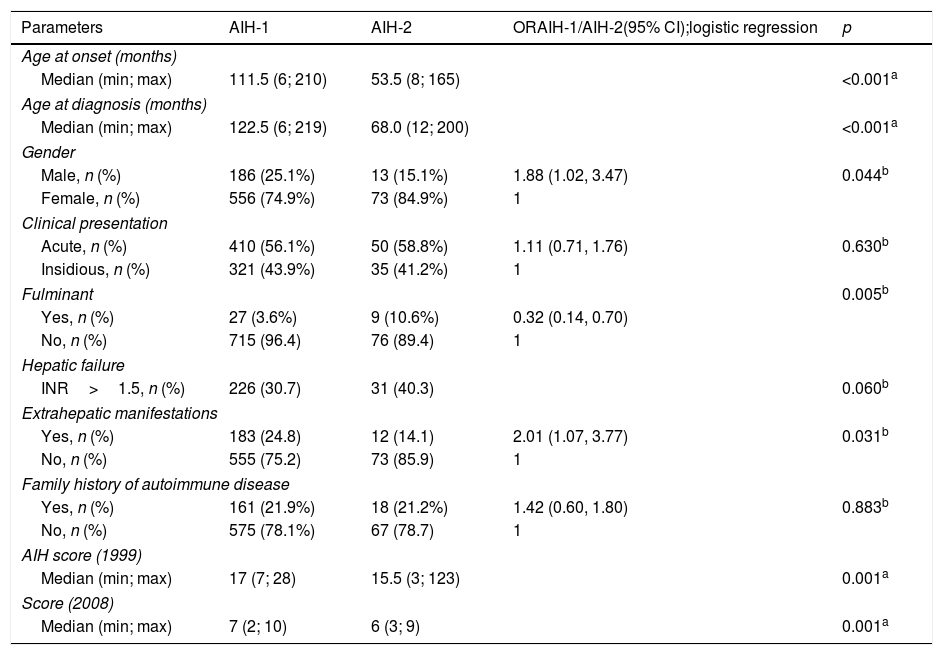

Demographic and clinical data (Table 1)The female sex was predominant among the patients (AIH-1: 74.9%, AIH-2: 84.9%). The median age at symptom onset were 111.5 (6; 210) and 53.5 (8; 165) months for the patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively (p<0.001).

Children with LKM1-positive findings were significantly younger (p<0.001). Patients had a median AIH score according to the 1999 and 2008 International AIH Scoring Systems of 17 (7; 28) and 7 (2; 10) for AIH-1 and 15.5 (3; 123) and 6 (3; 9) for AIH-2, respectively, revealing a significant difference between the groups (p=0.001).

Acute clinical onset was observed in 410 (56.1%) and 50 (58.8%) patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively. Insidious clinical symptoms were observed in 321 (43.9%) and 35 (41.2%) children with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively (Table 2). The risk for these two clinical presentations was not significantly different (p=0.630). Hepatic failure (INR>1.5) was observed in 226 (30.7%) and 31 (40.3%) patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively. The risk of hepatic failure was 1.6-fold higher in the AIH-2 group, which was only marginally significant (p=0.060). A total of 27 (3.6%) children with AIH-1 and nine (10.6%) children with AIH-2 had fulminant hepatic failure at initial presentation, and the difference was significant between the groups (p=0.005). Additionally, the risk was 3.1-fold higher in AIH-2. A family history of autoimmune disease, including diabetes, thyroid disease, Behçet's disease, psoriasis, and vitiligo, was observed in 161 (21.9%) patients with AIH-1 and in 18 (21.2%) patients with AIH-2 (p=0.883).

Extrahepatic autoimmune manifestations were present in 183 (24.8%) and 12 (14.1%) patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively, with a significant difference between the groups (p=0.031). The risk of extrahepatic autoimmune manifestations was two-fold higher in patients with AIH-1. The associated autoimmune diseases included systemic lupus erythematosus, Weber panniculitis, type 1 diabetes, thyroid disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, glomerulopathies, and arthritis.

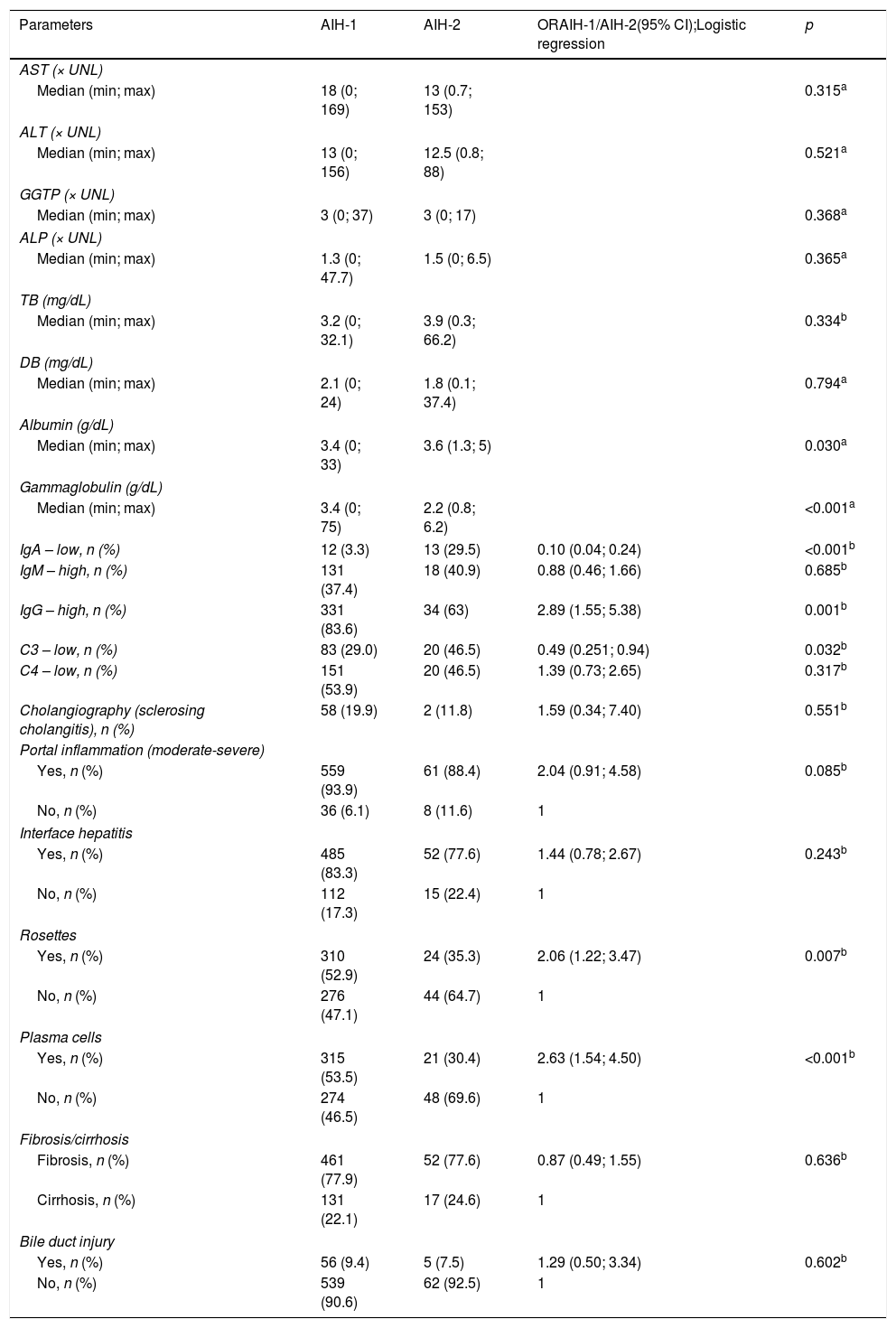

Laboratory and radiologic findings (Table 2)Regarding laboratory tests, no significant differences in serum DB, aminotransferase, GGTP, and ALP levels were observed between the groups. However, the albumin, gamma globulin, and/or IgG levels were significantly higher in the patients with AIH-1 than in those with AIH-2 (p=0.030 and p<0.001, respectively); the levels were lower in the patients with AIH-2 (p=0.001). Significantly lower C3 levels were noted in the children with AIH-2 (p=0.032), and no significant differences (p=0.317) in C4 levels were noted.

MRCP/cholangiography was performed in 309 children and adolescents, and the results were compatible with autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC) in 60 patients (58 patients with AIH-1 and two patients with AIH-2).

Histological findings (Table 2)Based on the results of the liver biopsies performed before the immunosuppressive treatment, hepatocyte rosettes and plasma cells were more prevalent in patients with AIH-1 (p=0.007 and p<0.001; 2.1-fold and 2.6-fold increased risk, respectively). Bile duct injury occurred in 61 patients; fibrosis was present in 513 patients and cirrhosis in 148 patients, without a significant difference between the groups.

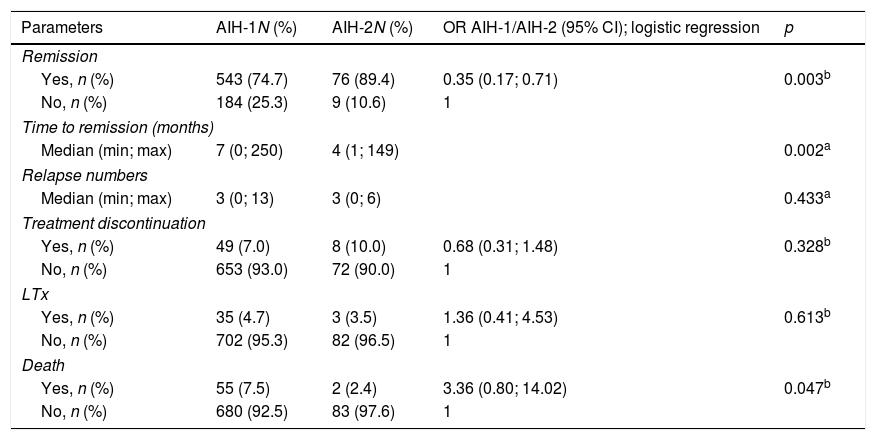

Treatments and outcomes (Table 3)In 94.1% of the 828 patients, the initial treatment for AIH was a combination of prednisone and azathioprine. A combination treatment including ursodeoxycholic acid was administered to 30.3%, mycophenolate mofetil to 3.7%, and cyclosporine to 6.3% of the patients. Follow-up duration was up to 23.8 years (mean, 7.08 years; median, 6.4 years).

After immunosuppression initiation, biochemical remission was achieved in 76.2% of the overall patients (AIH-1: 74.7%; AIH-2: 89.4%; p=0.003). The median time to biochemical remission were seven (0; 250) and four (1; 149) months for AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively (p=0.002).

Treatment was discontinued in 57 patients after complete remission. A total of 13 patients had relapsed post-suspension, and their treatment returned with immunosuppressive drugs. All patients with AIH-2 who discontinued the treatment did so on their own or, if for medical reasons, occurred prior to the recommendation of non-discontinuation of treatment, which currently exists, according to the international consensus.7

During treatment, the median number of biochemical relapses was three (0; 13) and the (0; 6) in the groups of patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively, with no difference between them (p=0.433).

Adverse effects during treatment, including alopecia, Cushing's syndrome, obesity, diabetes types 1 and 2, pulmonary embolism, stretch marks, infections (urinary and upper respiratory tract infections), pneumonia, tonsillitis relapses, and meningitis, were observed in 38.8% (n=322) of the patients.

During the study period, 37 adolescents (4.5%) became pregnant, and none had complications during gestation or post-partum. All babies were born alive without complications. Azathioprine was discontinued during the pregnancy, and the prednisone dose was not altered. After delivery, only those who breastfed did not receive azathioprine. There was no relapse in any of the 37 patients.

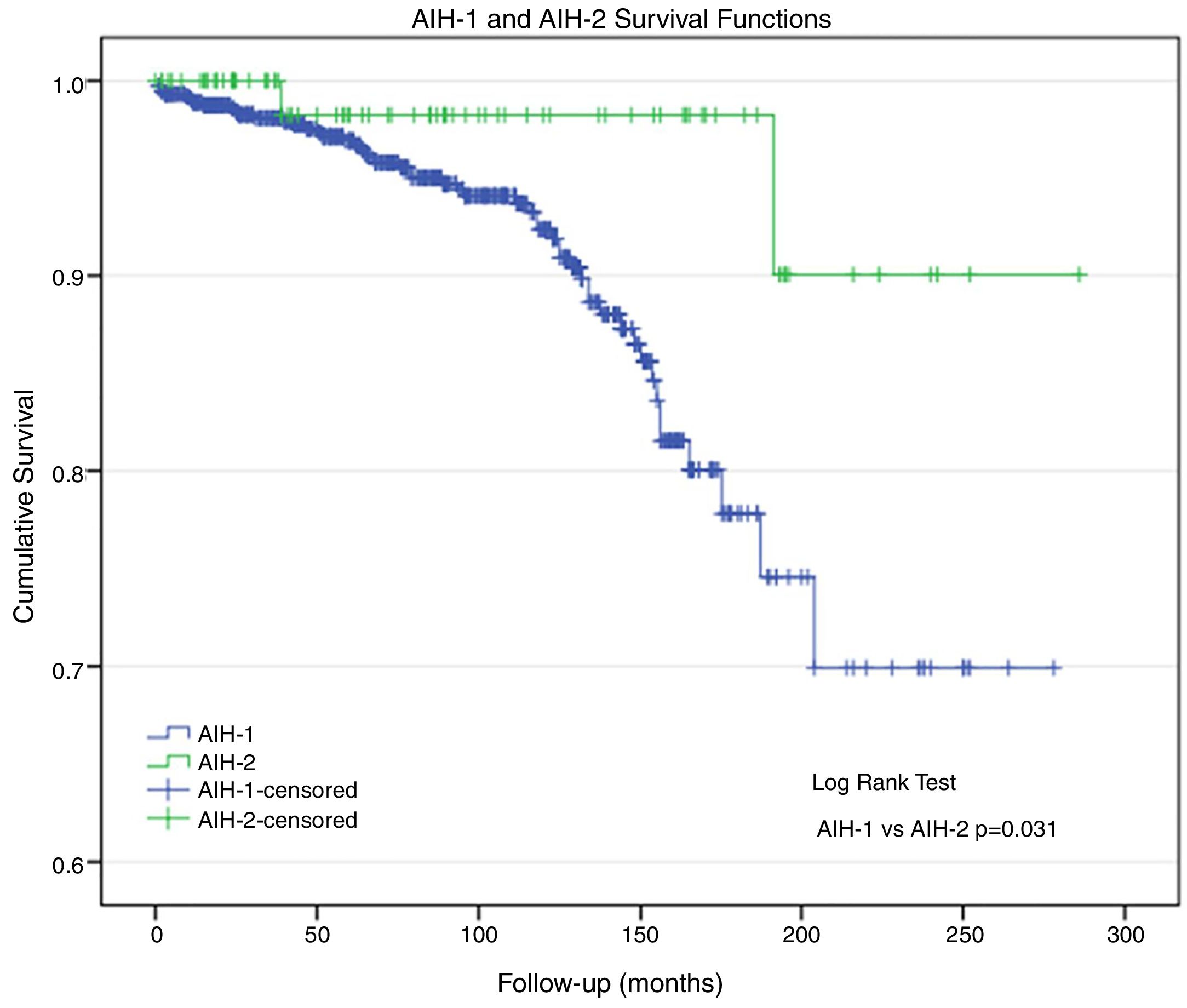

Morbidity and mortality (Table 3)A total of 38 patients underwent liver transplantation (LTx): 35 (4.7%) patients had AIH-1 and three (3.5%) patients had AIH-2. During the study period, 57 patients died: 55 (7.5%) patients with AIH-1 and two (2.4%) patients with AIH-2 (p=0.047). Deaths were related to AIH and its comorbidities. The actuarial survival rate was 92.5% and 97.6% in patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively (Fig. 1); at 96 months of follow-up, these probabilities were ∼94% and 98%, respectively. At 150 months, the probabilities were 86% and 98%, respectively. At the end of follow-up (AIH-1: 278 months; AIH-2: 286 months), the survival probabilities were ∼70% and 90%, respectively. The survival curve for patients with AIH-1 was almost equal to the overall survival curve, as only two deaths were observed among the 84 patients with AIH-2.

DiscussionThis study was the largest clinical series of children and adolescents with AIH published to date. In this Brazilian group, AIH-1 was more frequent. Moreover, patients with AIH-1 had a higher risk of undergoing LTx and death.

The earlier disease onset for AIH-2 in this study is similar to that found in the literature.8–10 The female/male sex distribution for AIH also corresponds to that in the literature, i.e., female sex predominance, especially among patients with AIH-1.

The clinical presentations of AIH-1 and AIH-2 were analogous, except for the fulminant form. Fulminant hepatitis is a very rare presentation of the disease, and when it occurs, it is more associated with AIH-2. In this study, the fulminant presentation occurred more frequently in the presence of anti-LKM1 positivity, which is consistent with Di Giorgio et al.11 and others in the literature.10–14

The extrahepatic manifestations associated with AIH are variable in both frequency and prevalence. Thyroid disorders are most frequently described, similar to the study by Bittencourt et al.15 Gregorio et al. reported extrahepatic manifestations, including thyroiditis, vitiligo, type 1 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disease, in 20% of children with AIH.13 The present findings are different from those of Gregorio et al., which may correspond to the regional differences and genetic susceptibility.16

The scores (1999 and 2008) for both AIH types were consistent with those of other studies.1,2,17 The patients who did not undergo biopsy at diagnosis met the international criteria for AIH, and no disagreements in the scores were observed in the present series. Mileti et al.17 examined the diagnostic effectiveness of the score in children. Initially, the pediatric population was not evaluated in accordance with the 1999 criteria. Subsequently, two studies presented controversial results regarding the use of both scores.18,19 Mileti et al.17 reported high sensitivity and specificity with the use of scores in the pediatric population; however, some limitations were also observed. The therapeutic response remains a fundamental diagnostic criterion, particularly in patients without autoimmunity markers, even if they do not attain a score indicating a definitive AIH diagnosis.20–22

The albumin levels reinforced disease severity, particularly in AIH-1, with worsening liver function. Elevated gamma globulin levels, particularly in AIH-1, are a significant sign in the differential diagnosis between the AIH types. This test is an important marker in AIH-1 diagnosis and the result may be normal in AIH-2, which reinforces the difference between the groups.

No IgM level differences or significant increases were found in the present patients. These data differ from those of Di Giorgio et al.11 who found elevated IgM levels without a real explanation.11

Diagnosing sclerosing cholangitis remains a challenge. Bile duct lesion detection does not definitively indicate ASC. Histology or MRCP alterations compatible with sclerosing cholangitis are not always observed in affected patients. Persistently elevated GGTP levels suggest biliary tract involvement, and long-term follow-up or explant evaluation allows diagnosis. Cholangiography was not performed in all patients. Several factors contributed to the difficulty in performing this test, e.g., need for anesthesia and costs. Since the study had a retrospective design, and there was no recommendation in the literature, several services performed this test only when the GGTP level did not decrease or when there was no therapeutic response to immunosuppressants. Thus, there may be a bias in this study regarding ASC prevalence, which is part of retrospective studies; however, the results remain important given the large number of patients included. The ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee recommends screening for overlap syndrome in patients with AIH.7

In this study, some patients did not undergo liver biopsy due to contraindications, such as coagulopathy (high INR), ascites, or severe thrombocytopenia. However, all these patients scored for AIH according to the international criteria, even without a scoring histology. Moreover, liver biopsy findings were not evaluated by a single pathologist, as this was a retrospective study that collected data from several centers, but followed the consensus criteria of Brazilian pathologists. Liver tissue examination prior to treatment is an important diagnosis component, and the guidelines recommend this exam to be performed at presentation.7 Despite these endorsements, the need for pre-treatment liver tissue examination has been challenged in children, as they usually exhibit significant liver dysfunction and coagulopathy.22 Björnsson et al.23 mentioned the importance of histology in typical AIH diagnosis and concluded that the majority of patients with AIH features are likely to have compatible liver histologies. In adults, the presence of cirrhosis at initial clinical presentation worsens the disease course, leading to a ten-year survival rate of ∼60% compared with 80% in patients without cirrhosis.23 However, Radhakrishnan et al.24 observed that the presence of cirrhosis did not affect long-term survival in children. Cirrhosis was a predominant finding in the initial presentation of both AIH types; however, this observation differs from the data obtained by Gregorio et al.16 and Saadah et al.,25 who reported a cirrhosis prevalence of 69% and 38% among patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively. In the current study, differences in the liver histopathological results were noted between the AIH groups, with a higher prevalence of rosettes and plasma cells in AIH-1, a finding that has not been reported in the literature. The presence of cirrhosis at the first disease presentation indicates AIH severity.

Therapeutic response is one of the best parameters to determine whether the clinical profile of hepatitis is attributable to an immunological cause. Disease remission is always the main immunosuppressive treatment goal. Generally, the therapeutic response is above 70% in patients with AIH-1 and 85% in those with AIH-2,16,26 findings similar with those of the present study.

This study revealed a reduced time to remission in patients with AIH-2. This finding is inconsistent with those by Gregorio et al.16

An important concern is non-adherence to treatment, particularly among adolescents.13 In this study, treatment was discontinued in both groups by the physician; treatment was also discontinued in some patients due to non-adherence. Ferreira et al.14 studied children who attained clinical-laboratory remission after a 24-month immunosuppression course and observed a 54.5% incidence of disease relapse after treatment, even in the presence of histological remission. They did not identify the predictive factors associated with relapse.

LTx is necessary for AIH treatment in ∼10% of cases26,27; it was performed in 10% of pediatric patients with AIH and 23% of patients with sclerosing cholangitis.26 In this study, LTx was performed in 4.7% and 3.5% of the patients with AIH-1 and AIH-2, respectively, indicating that the disease was well controlled with immunosuppressants.

The limiting factors of this study include the fact that it is retrospective and, consequently, there is the possibility of biases and incomplete data for some patients; however, importantly, it included patients from several secondary and tertiary reference centers, being the largest series of children and adolescents with AIH published to date. The data presented do not represent the actual prevalence of pediatric patients with autoimmune hepatitis in Brazil.

In summary, in this large clinical series of Brazilian children and adolescents with AIH, AIH-1 was more frequent; AIH-2 affected younger children, had higher remission rates, and had an earlier onset than AIH-1; and patients with AIH-1 had a higher risk of LTx and death.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Porta G, Carvalho E, Santos JL, Gama J, Borges CV, Seixas RB, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in 828 Brazilian children and adolescents: clinical and laboratory findings, histological profile, treatments, and outcomes. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:419–27.