To investigate the association between asthma and sleep duration in participants of the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional, national, school-based study, involving adolescents aged 12–17 years. In the period between 2013−14, data from 59,442 participants were analyzed. Bivariate analysis between current asthma and short sleep duration, defined as < 7 h/night, was performed separately with the other variables analyzed: sex, age group, type of school, weight categories, and common mental disorders. Then, different generalized linear models with Poisson family and logarithmic link functions were used to assess the independence of potential confounding covariates associated with both asthma and short sleep duration in the previous analysis. Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios and respective 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses performed.

ResultsPrevalence of current asthma was 13.4%, being significantly higher among students with short sleep duration (PR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.01–1.35; p = 0.034). This remained significant even after adjusting for the other study covariates.

ConclusionThere was a positive association between the prevalence of current asthma and short sleep duration among Brazilian adolescents. Considering the high prevalence and morbidity of the disease in this age group, the promotion of sleep hygiene should be considered as a possible health strategy aimed at contributing to better control of asthma in this population.

Asthma is the most common chronic non-communicable disease in childhood and adolescence, affecting 1%–18% of the population in different countries.1 According to International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the Brazilian prevalence of current asthma in adolescents aged 13−14 years was 19%.2 More recently, the Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), showed a prevalence of asthma of 13.1% among Brazilian adolescents.3

Previous studies4 have shown that the mean sleep duration among Brazilian adolescents is less than that recommended by the National Sleep Foundation (NSF), a world reference in sleep health based in the United States, which recently defined less than seven hours of sleep a night is not recommended.5 Sleep is an essential physiological process in promoting both physical and mental health, whose functions are not yet fully understood. The interaction between sleep and the circadian system influence the immune, endocrine, thermoregulatory, neurobehavioral, renal, cardiovascular, digestive systems, beyond the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle.6 In adolescence, physiological changes in sleep patterns occur, such as delayed bedtime and waking time, and a greater difference between hours of sleep during the week and on weekends.7

Nighttime exacerbations are characteristic of asthma, and affect up to 75% of patients. During sleep, oscillations in lung function occur, which are more pronounced in patients with asthma. This instability in lung volumes, associated with factors related to the nighttime, such as increased exposure to aeroallergens and colder air, may favor exacerbations of the disease.8

The associations between asthma and sleep have conflicting results in the literature9,10 and are still scarce in Brazil. The aim of this study was to investigate association between asthma and sleep duration in adolescents participating in ERICA.

MethodsStudy design and populationThis research is part of ERICA and, as such, followed its methodological precepts. This is a multicenter, national, school-based study carried out in a randomized sample of adolescents aged 12–17 years, representative of the group of adolescents enrolled in schools in municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants at the national and regional level, and of each capital and the Federal District. A more detailed description of the sample design can be found in a previous publication.11

Data collectionThe selected students answered self-administered questionnaires that included socio-demographic data, information on physical activity, eating behavior, presence of common mental disorders, medical history of chronic diseases, and sleep patterns, among other conditions. In addition, anthropometric measurements were performed. Data collection was performed using personal digital assistants (PDAs) and was supervised by field staff previously trained to apply standard study techniques.12

Exposure and outcome variablesThe asthma variable was assessed by the question: “In the last 12 months, how many wheezing attacks (wheezing crises) did you have?”, extracted from the ISAAC questionnaire asthma module for the 13−14 age group, translated and validated for Brazilian culture.13 Those who reported at least one attack in the past 12 months were classified as having current asthma. A positive response shows high sensitivity and specificity when compared to objective measurements of pulmonary function in adolescents with asthma.13

Sleep duration was evaluated by four questions in which the adolescents were asked to select the time when they usually sleep and wake up on ordinary weekdays and on the weekend. Sleep duration was considered as the difference, in hours, between the beginning and the end of sleep. The mean weekly duration of sleep was calculated as the weighted average of the hours of sleep over the weekdays and weekend, according to the equation: mean hours of sleep = (duration of sleep on the weekdays × 5) + (duration of sleep on the weekend days × 2)/7. Participants who reported less of seven hours of sleep per night were considered “short sleep duration” (SSD), and those who reported seven or more hours of sleep per night were considered “sufficient,” according to the criterion already used in other national studies.14 Sleep durations ≤3 or ≥14 h during the week or ≥18 h on weekends were considered inconsistent values, and were corrected when possible or disregarded.

In addition to these variables, covariates that could interfere with the study’s association of interest were also assessed, which were defined as follows: for common mental disorders, the General Health Questionnaire was used, a 12-item version (GHQ-12) validated for the Brazilian population. The GHQ measures the mental health, especially the psychiatric well-being, of an individual. This tool has a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 79% on detection of states of psychological distress as anxiety, depression, and somatoform symptoms, and consists of 12 items that assess the presence of the symptoms in the last two weeks. The responses of the individual items were coded as “absent” or “present” (0 or 1, respectively). Those with scores ≥ 3 were classified as cases.15

The classification of weight categories was performed using body mass index (BMI) curves, as proposed by the World Health Organization, specified by age and sex. Adolescents considered to have an adequate weight had a score of +1 > Z ≥ −2, adolescents with overweight had a score of +2 > Z ≥ +1, and obese adolescents were those with a score of Z ≥ +2.16 For analysis purposes, the variable was divided into two categories: “excess weight” (overweight and obese) and the rest of the sample (eutrophic and underweight). Anthropometric measurements were performed with the individuals wearing light clothing and bare feet using an electronic scale (Líder® model P200 M – São Paulo, Brazil,) with a capacity of up to 200 kg and an accuracy of 50 g; height was measured using a portable stadiometer (Alturaexata® – Minas Gerais, Brazil) with an accuracy of 0.1 cm.11 The following sociodemographic variables were also evaluated: gender, age group (12–14 years or 15–17 years), and type of school (public or private).

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics was reported by frequencies and means. Bivariate analysis was performed separately between current asthma and sleep duration with the others variables: sex, age group, type of school, weight categories, and common mental disorders. Prevalence ratios (PR) and respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using a bivariate Poisson regression model. Then, different generalized linear models (GLMs) with Poisson family and logarithmic link functions were created to evaluate the association between current asthma and sleep duration, adjusted for the covariables significantly associated with each one in the bivariate analysis. Finally, the same statistical model was used to assess the independence of potential confounding covariates associated with both asthma and SSD in the previous analysis. The value of p < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses performed.

To obtain estimates of central tendency and variances, and measures resulting from them, special routines were necessary to deal with the sample complexity therefore the analysis was performed using Stata software, v. 14.0 (StataCorp — College Station, TX, United States) using the SURVEY command.

Ethical aspectsThe study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the Institute of Studies in Collective Health of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Process 45/2008 of 2/11/2009), and of the 26 states and the Federal District. Participants’ privacy and data confidentiality were guaranteed throughout the study.

ResultsBetween 2013 and 2014, 74,589 adolescents were evaluated. Those who answered the question about asthma as “I don't know/I don't remember” were excluded from the study, as well as those with values of sleep duration considered inconsistent even after correction; thus, a total of 59,442 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. S1).

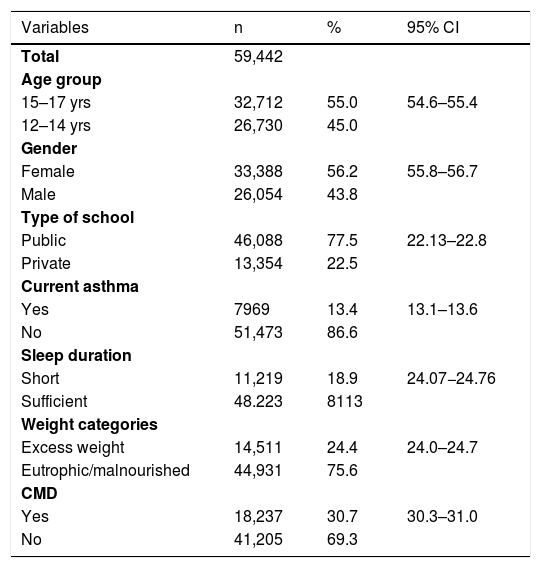

Among the adolescents evaluated, 55.3% were aged between 15 and 17 years and 56.2% were female. The prevalence of current asthma was 13.4% (95% CI: 13.1%–13.7%) and 18.8% (95% CI: 18.5%–19.1%) of adolescents had SSD (Table 1).

General characteristics of the sample. Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), Brazil, 2013–14.

| Variables | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 59,442 | ||

| Age group | |||

| 15–17 yrs | 32,712 | 55.0 | 54.6–55.4 |

| 12–14 yrs | 26,730 | 45.0 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 33,388 | 56.2 | 55.8–56.7 |

| Male | 26,054 | 43.8 | |

| Type of school | |||

| Public | 46,088 | 77.5 | 22.13–22.8 |

| Private | 13,354 | 22.5 | |

| Current asthma | |||

| Yes | 7969 | 13.4 | 13.1–13.6 |

| No | 51,473 | 86.6 | |

| Sleep duration | |||

| Short | 11,219 | 18.9 | 24.07−24.76 |

| Sufficient | 48.223 | 8113 | |

| Weight categories | |||

| Excess weight | 14,511 | 24.4 | 24.0–24.7 |

| Eutrophic/malnourished | 44,931 | 75.6 | |

| CMD | |||

| Yes | 18,237 | 30.7 | 30.3–31.0 |

| No | 41,205 | 69.3 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CMD, common mental disorders.

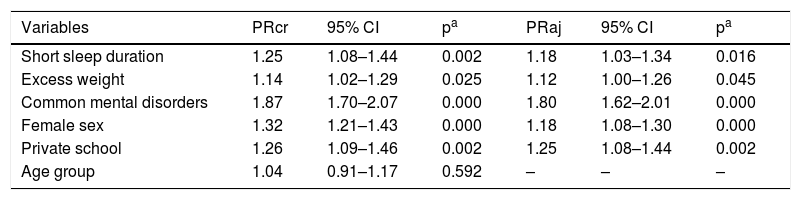

Current asthma was significantly associated with SSD (PR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.08–1.44) in the bivariate model. The prevalence of current asthma was significantly higher among students with excess weight, presence of common mental disorders, female sex, and private schools (Table 2). These associations remained significant after the adjustment between them (Table 2).

Crude and adjusted analysis between current asthma and study variables. Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), Brazil, 2013-2014.

| Variables | PRcr | 95% CI | pa | PRaj | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short sleep duration | 1.25 | 1.08–1.44 | 0.002 | 1.18 | 1.03–1.34 | 0.016 |

| Excess weight | 1.14 | 1.02–1.29 | 0.025 | 1.12 | 1.00–1.26 | 0.045 |

| Common mental disorders | 1.87 | 1.70–2.07 | 0.000 | 1.80 | 1.62–2.01 | 0.000 |

| Female sex | 1.32 | 1.21–1.43 | 0.000 | 1.18 | 1.08–1.30 | 0.000 |

| Private school | 1.26 | 1.09–1.46 | 0.002 | 1.25 | 1.08–1.44 | 0.002 |

| Age group | 1.04 | 0.91–1.17 | 0.592 | – | – | – |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PRcr, crude prevalence ratio; PRaj, prevalence ratio adjusted for nutritional status, common mental disorders, gender, school type.

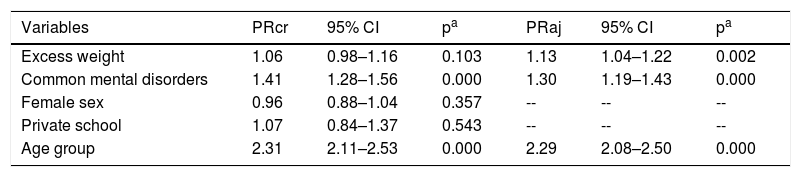

Besides asthma, SSD was significantly associated with older age group, presence of common mental disorders, and excess weight (Table 3). After adjusted multivariate analysis, the association of SSD with these last two covariates was maintained (Table 3).

Crude and adjusted analysis between short sleep duration and study variables. Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), Brazil, 2013–2014.

| Variables | PRcr | 95% CI | pa | PRaj | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excess weight | 1.06 | 0.98–1.16 | 0.103 | 1.13 | 1.04–1.22 | 0.002 |

| Common mental disorders | 1.41 | 1.28–1.56 | 0.000 | 1.30 | 1.19–1.43 | 0.000 |

| Female sex | 0.96 | 0.88–1.04 | 0.357 | -- | -- | -- |

| Private school | 1.07 | 0.84–1.37 | 0.543 | -- | -- | -- |

| Age group | 2.31 | 2.11–2.53 | 0.000 | 2.29 | 2.08–2.50 | 0.000 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PRcr, crude prevalence ratio; PRaj, prevalence ratio adjusted for asthma, nutritional status, common mental disorders, gender, school type.

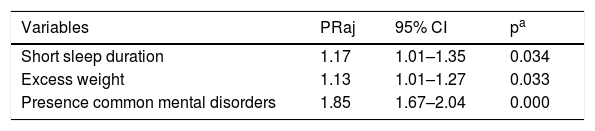

Common mental disorders and excess weight were considered as confounding variables and included in the final model. Current asthma and SSD remained significantly associated (PR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.01–1.35), showing that these are independent factors for both conditions (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis between current asthma, short sleep duration, and confounding factors. Study of Cardiovascular Risks in Adolescents (ERICA), Brazil, 2013–2014.

| Variables | PRaj | 95% CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short sleep duration | 1.17 | 1.01–1.35 | 0.034 |

| Excess weight | 1.13 | 1.01–1.27 | 0.033 |

| Presence common mental disorders | 1.85 | 1.67–2.04 | 0.000 |

The prevalence of current asthma in adolescents was significantly associated with SSD, regardless of possible confounding factors such as “excess weight” and the presence of common mental disorders. This finding is consistent with those of other national and international studies. Urrutia-Pereira et al., in a recent study involving 700 children aged 4–10 years with asthma and/or rhinitis and 454 controls from Latin American countries, including Brazil, showed that patients with asthma had the worst scores on the Sleep Habits Questionnaire, completed by their caregivers, in comparison to controls. This finding was present, even when asthma treatment was adequate, suggesting that the disease causes sleep impairment even when well controlled.17 In 2013, 2529 11-year-old children participating in the Prevention and Incidence of Asthma and Mite Allergy Study (PIAMA) answered questionnaires on different aspects of sleep. Those with more frequent asthma symptoms reported greater fatigue and drowsiness throughout the day, regardless of bedtime, duration, and quality of sleep.9 On the other hand, in 2014, Meltzer et al., in a study involving 298 adolescents between 12–17 years old, 51% male and 48% with asthma, assessed sleep duration, sleep hygiene, and insomnia in patients with and without asthma. There was no significant association between sleep duration and asthma, although patients with severe asthma reported more insomnia than non-asthmatics, in addition to having more sleepiness during the day.10

The association between asthma and sleep was also assessed by longitudinal studies. Krouse et al. compared the sleep/wake cycles of individuals with mild to moderate/persistent asthma and controls for seven consecutive days, using wrist actigraphy, and observed a positive association between the level of asthma control and the quality of sleep.18 Another study followed 38 patients between 9 and 19 years of age with asthma for two weeks, showed that a lower number of sleep hours was associated with a lower peak expiratory flow (PEF) and less release of morning cortisol, but without association with greater severity of asthma symptoms. However, those who reported worse sleep quality did not show a functional change or cortisol release; nonetheless, they reported more severe asthma symptoms the next day.19 The authors conclude that the amount of sleep can predict biological outcomes (PEF%, morning cortisol levels), while sleep quality, a subjective measure, was related to the self-reported severity of asthma symptoms, a subjective outcome.19

Collectively, these results point to an association between SSD and the presence of asthma and severity of symptoms, and suggest a possible bi-directionality of this association. However, due to the cross-sectional character of the present study, it was not possible to infer this hypothesis.

Evidence suggests that not getting enough sleep is often the result of poor sleep hygiene,20 a collective term used to refer to behaviors and habits that can either facilitate sleep or inhibit/interfere with sleep. These measurements includes creating an environment that is conducive to sleep, such as having a consistent routine, and avoiding caffeine before bed, avoiding use of technology before bed, and regulating the temperature of the bedroom.20

Regarding the sleep pattern, girls seem to sleep more hours than boys, as was observed in meta-analysis.21 However, among ERICA participants, boys in the 12−14 year age group had a longer mean sleep duration than girls, and from 15 years of age there was a more pronounced decline in the number of hours of sleep.22 In the present sample, after adjusting of the multivariate model, both sex and age group did not show independence in relation to the association between asthma and SSD.

An association was found between asthma and the presence of excess weight, a finding that has been widely described in the literature.23 The so-called “asthma-obese” has been recognized as a distinct phenotype with increasing incidence in childhood and adolescence, and is associated with a poor response to standard anti-inflammatory treatment with corticosteroids, with worse disease control.24 A meta-analysis revealed twice the risk of developing asthma in obese children compared to eutrophic children, suggesting that obesity is an independent risk factor for asthma.25 A study carried out among high school students from Florida, United States, evaluated whether the BMI changed the association between sleep duration and asthma. It was observed that SSD was associated with asthma in overweight adolescents, while no significant association was seen in those with normal BMI.26 A recent study evaluating this association among ERICA participants, showed that SSD is associated with overweight/obesity (PR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.00–1.17).27 In the present sample, the association between this variable and asthma remained significant after adjusting for SSD, showing that excess weight is an independent factor in the association between asthma and sleep.

Another important result of this study was the significant association between asthma and common mental disorders. It is noteworthy that it had a high prevalence among the participants in this study, about 30%, with this proportion being higher among girls and in the age group of 15–17 years. As observed in relation to obesity, the association between asthma, SSD, and common mental disorders remained after adjusting for possible confounding variables. This finding is corroborated by other international studies. Anxiety, depression, denial of the disease, and presence of family conflicts have been associated with lower adherence to treatment and higher morbidity and mortality from asthma.28 In addition, the analysis of emotional and behavioral disorders conducted in children and adolescents with asthma shows a higher prevalence of emotional disorders among these individuals than the general population.28 Furthermore, studies suggest that there is an interaction between sleep behavior and psychopathology so that sleep problems contribute to the intensity and maintenance of mental disorders, and the treatment of both conditions seems to influence each other in a positive way.29

The present study has limitations inherent to its cross-sectional design, which does not allow establishing causal relationships between the variables studied. More precise objective measures on sleep duration such as actigraphy and polysomnography were not performed due to the difficulty of using these methods in epidemiological studies with large sample sizes. However, self-reported sleep duration is widely indicated and used worldwide to measure sleep duration in adolescents. In addition, studies report that questionnaires are a reliable measure and that self-reported sleep duration estimates are similar to actigraphy.30 However, the size and representativeness of the sample, the use of standardized questionnaires, and the control and quality of the data support the importance of these findings.

There was an association between the presence of asthma and SSD, regardless of sociodemographic factors, weight status, and psychological distress among Brazilian adolescents. Considering the high prevalence and morbidity of asthma in this age group, the promotion of sleep hygiene should be considered as a possible health strategy aimed at contributing to a better control of asthma in this population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.