To identify, using a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, which risk factors are significantly associated with neonatal mortality in Brazil, and to build a comprehensive national analysis on neonatal mortality.

SourcesThis review included observational studies on neonatal mortality, performed between 2000 and 2018 in Brazilian cities. The MEDLINE, Elsevier, Cochrane, LILACS, SciELO, and OpenGrey databases were used. For the qualitative analysis, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used. For the quantitative analysis, the natural logarithms of the risk measures and their confidence intervals were used, as well as the DerSimonian and Laird method as a random effects model, and the Mantel–Haenszel model for heterogeneity estimation. A confidence level of 95% was considered.

Summary of findingsThe qualitative analysis resulted in six studies of low and four studies of intermediate-low bias risk. The following exposure factors were significant: absence of partner, maternal age ≥35 years, male gender, multiple gestation, inadequate and absent prenatal care, presence of complications during pregnancy, congenital malformation in the assessed pregnancy, Apgar<7 at the fifth minute, low and very low birth weight, gestational age≤37 weeks, and caesarean delivery.

ConclusionThe most significant risk factors presented in this study are modifiable, allowing aiming at a real reduction in neonatal deaths, which remain high in the country.

Identificar, através de uma revisão sistemática e da metanálise de estudos observacionais, quais fatores de risco associam-se significativamente com a mortalidade neonatal no Brasil e construir uma análise nacional abrangente sobre a mortalidade neonatal.

FontesForam avaliados os estudos observacionais sobre mortalidade neonatal realizados entre os anos 2000 e 2018 em cidades brasileiras. Usaram-se as bases MEDLINE, Elsevier, Cochrane, LILACS, SciELO e OpenGrey. Para a análise qualitativa, foi utilizada a Escala Newcastle-Ottawa. Para a análise quantitativa, foram utilizados os logaritmos naturais das medidas de risco e de seus intervalos de confiança, o método de DerSimonian e Laird como modelo de efeitos aleatórios, e o modelo de Mantel-Haenszel para estimativa da heterogeneidade. Considerou-se nível de confiança de 95%.

Resumo dos achadosA análise qualitativa resultou em seis estudos de baixo e quatro estudos de intermediário-baixo risco de viés. Foram significativos os seguintes fatores de exposição: ausência de companheiro, idade materna ≥ 35 anos, sexo masculino, gestação múltipla, pré-natal inadequado e ausente, presença de intercorrências durante a gestação, de malformação congênita na gestação em estudo, Apgar < 7 no quinto minuto, baixo e muito baixo peso ao nascer, idade gestacional ≤ 37 semanas e parto cesariano.

ConclusãoOs fatores de risco mais significativos apresentados neste estudo são modificáveis, o que possibilita almejar uma redução real das mortes neonatais, que ainda permanecem elevadas no país.

Neonatal death is defined as the death of a newborn before completing 28 days of life.1,2 In Brazil, the neonatal mortality rate in 2016 consisted of eight neonatal deaths per 1000 live births – a significant reduction when compared to 1990, when it was 26 neonatal deaths per 1000 live births.3,4 In 2011, the country reached goal four of the Millennium Development Goals, a commitment of the member governments of the United Nations to reduce infant mortality.3 The Brazilian neonatal mortality rate, despite this reduction, is still high and unevenly distributed regionally, with the difference between the North/Northeast and South/Southeast regions being the most discrepant.5

The reduction of this rate is a goal to be pursued and a reality that can be achieved, since preventable factors, such as low birth weight, prematurity, neonatal asphyxia, and low-quality prenatal care are the main reasons for this high value.6–8 However, the maternal causes constitute a complementary factor of equal importance, with a significant contribution to neonatal mortality in developing countries.5,8 Nevertheless, there is no systematic evaluation of all these factors in Brazil at this time.

A systematic review with meta-analysis constitutes a real possibility to assess the impact of risk factors on neonatal mortality in the Brazilian territory, aiding clinical decision-making and the professionals’ epidemiological understanding of the situation, especially by public health managers in Brazil.9 The study aims to identify, through a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, which risk factors are significantly associated with neonatal mortality in Brazil, and to build a comprehensive national analysis on the subject.

MethodsA PROSPERO protocol (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) was published under No. CRD42018108716.

Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias analysis were independently performed by two authors. The differences were resolved by consensus between the authors; if there was no consensus, a third author would end the impasse.

Eligibility criteriaThe inclusion criteria consisted of the following items: observational studies on neonatal mortality; studies carried out between 2000 and 2018; studies carried out in Brazilian cities; studies that used adjusted risk measures, together with their confidence intervals; studies that employed one or more of the following exposure factors: maternal schooling and/or marital status of the mother and/or maternal age (years) and/or gender of the newborn and/or type of delivery and/or previous stillbirth and/or type of gestation and/or adequacy of prenatal care and/or maternal complications and/or birth weight (g) and/or gestational age (weeks) and/or congenital malformation and/or Apgar at the 5th minute of life.

DatabasesThe main databases used for this study were MEDLINE, accessed via PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and Bireme (http://bvsalud.org/). The secondary database was Elsevier (https://www.sciencedirect.com/). The regional databases were LILACS (http://bvsalud.org/) and SciELO (http://www.scielo.org/php/index.php). The grey literature database was OPENGREY (http://www.opengrey.eu/).

Search strategyThe search strategy was defined based on the PECOS strategy (Patients | Exposure | Comparison | Outcome | Type of study). Therefore, two base strategies were constructed, one in the English language, using MeSH terms (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh), and another in the Portuguese language, using DeCS terms (http://decs.bvs.br/), as follows:

- 1.

(early neonatal mortality OR neonatal mortality OR perinatal mortality OR infant mortality) AND (risk factors OR socioeconomic factors OR low birth weight OR perinatal care) AND (Brazil OR Brasil) AND (case control studies OR cohort studies);

- 2.

(mortalidade neonatal OR mortalidade perinatal OR mortalidade infantil) AND (fatores de risco OR fatores socioeconômicos OR baixo peso ao nascer) AND (caso-controle OR coorte).

Study selection consisted of three stages: title phase, abstract phase, and full-article phase, which started after the searches in all the databases. In addition to this selection, the inclusion of the articles was complemented by the search for help from specialists in the area upon finding studies relevant to this review. Duplicates were removed with the help of Mendeley software (Mendeley, version 1.17.1,1 Elsevier – NY, USA).

Data extractionA spreadsheet was created using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft, Excel software, version 2016, WA, USA) containing the following elements: name of the authors of the study; city and state of the study; year of study; type of study; total number of study subjects; adjusted risk measures, and confidence intervals of the included exposure factors.

Factors of exposure and outcomeThe assessed exposure factors were: “maternal schooling,” “mother's marital status,” “maternal age (years),” “newborn's gender,” “previous stillbirth,” “type of pregnancy,” “prenatal care adequacy,” “complications during the pregnancy,” “birth weight,” “congenital malformation,” “Apgar at the 5th minute,” “gestational age (weeks),” and “type of delivery.” The outcome was neonatal mortality.

Risk of bias in individual studiesThe risk of bias was based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)10 to assess the quality of non-randomized studies in a meta-analysis. The NOS evaluates the bias regarding three aspects: the selection of study groups; the comparability of groups; the determination of exposure for case–control studies, or the outcome of interest for cohort studies. A maximum of four stars is given to the first aspect; to the second, two stars; and, finally, to the third, three stars.

Analysis of dataThe data analysis was based on the quantitative study of the variables. Stata 12 software (StataCorp – College Station – TX, USA) was used for this investigation. The analyzed data were the adjusted risk measures in each exposure factor analyzed, in addition to their confidence intervals. The natural logarithms of the risk measures and of their confidence intervals, the DerSimonian and Laird method as a random effects model, and the Mantel–Haenszel model for estimation of heterogeneity were used. A confidence level of 95% was considered.

Heterogeneity was considered important when I2 was >50%. If necessary, the sensitivity analysis was performed by removing the studies one by one to investigate the origin of the divergence. The evaluation of publication bias was performed using a funnel plot.

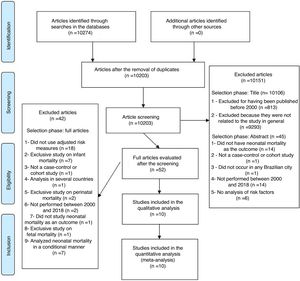

ResultsStudy selectionThe search in the databases identified 10,274 articles. Of these, 61 were duplicates, resulting in 10,203 articles. After reading all the titles, 98 articles were chosen to be analyzed in the abstract phase. At the end of this phase, 17 articles were selected, of which ten articles were included in the study3,6,11–18 (Fig. 1). The overall characteristics of the ten studies included in the analysis are available in Table 1 and the characteristics relevant to the quantitative analysis are shown in Table 2.

Overall characteristics of included studies.

| Analyzed studies | Year | City/State | Study type | Number of subjects | Analyzed variables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Lansky et al.3 | 2014 | Several cities in the five Brazilian macro-regions | Cohort | 24,329 | Maternal schooling | Maternal marital status | Maternal age | Newborn's gender | Previous stillbirth | Type of pregnancy | Adequacy of prenatal care | Complications during pregnancy | Birth weight | Congenital malformation | Apgar at the 5th minute |

| II | Lima et al.17 | 2012 | Serra/ES | Cohort | 32,275 | Maternal schooling| Maternal age | Type of pregnancy | Adequacy of prenatal care | Birth weight | Type of delivery |

| III | Zanini et al.13 | 2011 | 35 micro-regions/RS | Cohort | 138,407 | Previous stillbirth | Birth weight | Congenital malformation | Apgar in the 5th minute | Gestational age | Type of delivery |

| IV | Garcia et al.16 | 2019 | Florianópolis/SC | Cohort | 15,879 | Adequacy of prenatal care | Birth weight | Congenital malformation | Apgar in the 5th minute | Type of delivery | Gestational age |

| V | Almeida and Barros12 | 2004 | Campinas/SP | Case–control | 351 | Birth weight | Gestational age |

| VI | Nascimento et al.11 | 2012 | Fortaleza/CE | Case–control | 396 | Newborn's gender | Adequacy of prenatal care | Birth weight | Gestational age |

| VII | Kassar et al. 6 | 2013 | Maceió/AL | Case–control | 408 | Adequacy of prenatal care | Birth weight |

| VIII | Schoeps et al. 14 | 2007 | São Paulo/SP | Case–control | 459 | Maternal marital status | Adequacy of prenatal care | Complications during pregnancy | Birth weight | Gestational age |

| IX | Paulucci and Nascimento15 | 2007 | Taubaté/SP | Case–control | 392 | Birth weight | Congenital malformation |

| X | Mendes et al.18 | 2006 | Caxias do Sul/RS | Case–control | 354 | Adequacy of prenatal care | Birth weight | Type of delivery | Gestational age |

Characteristics of the studies included in the quantitative analysis.

| Analyzed variables | Factors | Analyzed studies | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal schooling | Complete Elementary School (8–11 years) | (3)(17) | 4.240.92 | [1.61–11.16][0.59–1.41] |

| Incomplete Elementary School (4–7 years) | (3)(17) | 3.600.94 | [1.43–9.07][0.60–1.47] | |

| Maternal marital status | Mother without a partner | (3)(14) | 2.491.80 | [1.69–3.66][1.00–3.00] |

| Maternal age | Maternal age≥35 years | (3)(17) | 1.621.54 | [0.95–2.78][1.04–2.29] |

| Newborn's gender | Male gender | (3)(11) | 1.492.09 | [1.08–2.05][1.09–4.03] |

| Previous stillbirth | Presence of previous stillbirth | (3)(13) | 3.621.29 | [2.05–6.41][1.01–1.65] |

| Type of pregnancy | Multiple pregnancy | (3)(17) | 4.792.26 | [2.37–9.68][1.03–4.96] |

| Adequacy of prenatal care | Inadequate prenatal care | (3)(11)(6)(14)(16)(18) | 2.842.032.492.003.041.45 | [1.44–5.62][1.03–3.99][1.14–5.40][2.00–3.50][1.61–5.97][0.44–4.77] |

| Absence of prenatal care | (14)(17) | 16.103.48 | [4.70–55.40][1.86–6.49] | |

| Complications during pregnancy | Presence of complications during pregnancy | (3)(14) | 6.078.20 | [3.85–9.55][5.00–13.50] |

| Birth weight | Birth weight between 1500 and 2499g | (3)(17)(13) | 5.192.365.46 | [2.44–11.04][1.46–3.83][4.07–7.31] |

| Birth weight less than 1500g | (3)(17)(13) | 32.275.4941.15 | [12.65–82.35][2.52–11.96][29.25–57.87] | |

| Birth weight less than 2500g | (12)(11)(6)(14)(15)(16)(18) | 3.8414.752.5717.3022.809.4634.60 | [1.18–12.50][5.26–41.35][1.16–5.72][8.40–35.60][7.52–69.12][4.06–23.60][3.84–311.50] | |

| Congenital malformation | Presence of congenital malformation | (3)(13)(15)(16) | 16.5514.7912.916.12 | [6.47–42.38][11.18–19.59][2.13–78.38][2.14–15.67] |

| Apgar at the 5th minute | Presence of Apgar score<7 at the 5th minute | (3)(13)(16) | 15.7911.3919.08 | [6.54–38.14][8.51–15.25][8.78–42.92] |

| Gestational age | Gestational age<37 weeks | (12)(11)(14)(13)(16)(18) | 5.373.418.801.846.0943.46 | [1.83–17.98][1.09–4.03][4.30–17.80][1.42–2.39][2.58–15.23][10.26–83.97] |

| Type of delivery | Caesarean delivery | (17)(13)(18) | 1.520.802.36 | [1.17–1.97][0.68–0.93][0.70–7.61] |

The ten studies included in the present analysis were qualitatively assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Four studies3,13,16,17 obtained a high classification, i.e., they show low risk of bias. However, six studies6,11,12,14,15,18 obtained an intermediate-high classification, thus showing an intermediate-low risk (Table 3).

Bias risk assessment of included studies.

| Analyzed studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | |||||

| (3) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

| (17) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

| (13) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

| (16) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

| Case–control | |||||

| (12) | *** | * | ** | 6*/9* | Intermediate-high quality |

| (11) | *** | * | ** | 6*/9* | Intermediate-high quality |

| (6) | *** | * | ** | 6*/9* | Intermediate-high quality |

| (14) | *** | * | ** | 6*/9* | Intermediate-high quality |

| (15) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

| (18) | *** | * | *** | 7*/9* | High quality |

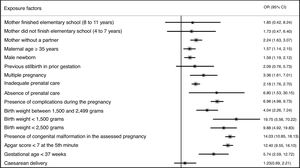

Fig. 2 shows the overall association between the analyzed factors and the association with neonatal mortality, represented in the image by the final adjusted odds ratios (faOR) and their respective confidence intervals. The result of each exposure factor can be seen below, separately.

Maternal schooling could only be analyzed in two ways: complete elementary school (8–11 years of schooling) and incomplete elementary school (4–7 years of schooling). Complete elementary school did not show a significant association with neonatal mortality (faOR=1.853; 95% CI: [0.417–8.241]; p=0.418; I2=87.4%; p=0.005). The same was observed for incomplete elementary school (faOR=1.727, 95% CI: [0.466–6.400], p=0.414, I2=84.8%, p=0.010).

Mother's marital statusThe pregnancy of mothers who did not have a partner showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=2.236, 95% CI: [1.630–3.068], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.344).

Maternal ageThe pregnancy of mothers aged 35 years or older showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=1.568, 95% CI: [1.141–2.154], p=0.006, I2=0.0%, p=0.882).

Newborn's genderMale newborns had a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=1.591, 95% CI: [1.193–2.121], p=0.002, I2=0.0%, p=0.362).

Previous stillbirthThe pregnancy of mothers who had a previous stillbirth did not show a significant association with neonatal mortality (faOR=2.090, 95% CI: [0.762–5.733], p=0.152, I2=90.6%, p=0.001).

Type of pregnancyA multiple pregnancy showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=3.361, 95% CI: [1.612–7.009], p=0.001, I2=48.7%, p=0.163).

Adequacy of prenatal careIt was only possible to analyze the inadequacy and absence of prenatal care. Inadequate prenatal care showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=2.182, 95% CI: [1.761–2.703], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.771). The same was observed with the absence of prenatal care (faOR=6.799, 95% CI: [1.534–30.147], p=0.012, I2=78.8%, p=0.030).

Complications during pregnancyThe presence of complications during pregnancy showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=6.961, 95% CI: [4.979–9.733], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.381).

Birth weightIt was only possible to analyze birth weight between 1500 and 2499g (faOR=4.044, 95% CI: [2.260–7.238], p<0.001, I2=77.0%, p=0.013), lower than 1500g (faOR=19.752; 95% CI: [5.556–70.223]; p<0.001; I2=90.7%; p<0.001), and lower than 2500g (faOR=9.876; 95% CI: [4.920–19.826]; p<0.001; I2=69.4%; p=0.003). After the sensitivity analysis, birth weight between 1500 and 2499g (faOR=5.424, 95% CI: [4.128–7.126], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.902), lower than 1500g (faOR=39.995, 95% CI: [29.026–55.109], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.633), and lower than 2500g (faOR=15.519, 95% CI: [9.997–24,092]; p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.684) continued to show a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality after removal of one study in the first and the second described situations,17 and after the removal of another two in the third situation.6,12

Congenital malformationNewborns with a congenital malformation showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=14.025, 95% CI: [10.849–18.132], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.402).

Apgar score at the 5th minuteThe presence of an Apgar score less than 7 at the 5th minute showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=12.397, 95% CI: [9.545–16.102], p<0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.417).

Gestational ageA gestational age <37 weeks showed a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality (faOR=5.738, 95% CI: [2.589–12.716], p<0.001, I2=86.9%, p<0.001). After the sensitivity analysis, it continued to show a significantly higher chance of neonatal mortality after the removal of three studies11,13,18 (faOR=7.130; 95% CI: [4.329–11.742]; p<0.001; I2=0.0%; p=0.706).

Type of deliveryCaesarean delivery did not show a significant association with neonatal mortality (faOR=1.233, 95% CI: [0.688–2.210], p=0.483, I2=89.7%, p<0.001). When exploring heterogeneity, there was a significantly greater chance of neonatal mortality after a study was removed17 (faOR=1.551, 95% CI: 1.202–2.000, p=0.001, I2=0.0%, p=0.480).

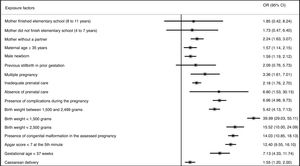

It was not possible to perform a sensitivity analysis on the following factors: complete elementary school, incomplete elementary school, presence of previous stillbirth, and absence of prenatal care, since these analyzes consisted of only two studies. Fig. 3 shows the final overall association after the sensitivity analysis.

Regarding the publication bias, it was not possible to evaluate it due to the number of studies included in each analysis. Table 4 shows a final summary-table of the results obtained in the quantitative analysis.

Summary of the results obtained in the quantitative analysis.

| FACTORS | Studies included in the analysis | Total number of analyzed subjects | Final adjusted OR | Final (95%) CI | p | I2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete elementary school (8–11 years) | (3) (17) | 56,604 | 1.853 | [0.417–8.241] | 0.005 | 87.4% | 0.418 |

| Incomplete elementary school (4–7 years) | (3) (17) | 56,604 | 1.727 | [0.466–6.400] | 0.010 | 84.8% | 0.414 |

| Mother without partnerb | (3) (14) | 24,788 | 2.236 | [1.630–3.068] | 0.344 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Maternal age≥35 yearsb | (3) (17) | 56,604 | 1.568 | [1.141–2.154] | 0.882 | 0.0% | 0.006 |

| Male genderb | (3) (11) | 24,725 | 1.591 | [1.193–2.121] | 0.362 | 0.0% | 0.002 |

| Presence of previous stillbirth | (3) (13) | 162,736 | 2.090 | [0.762–5.733] | 0.001 | 90.6% | 0.152 |

| Multiple pregnancyb | (3) (17) | 56,604 | 3.361 | [1.612–7.009] | 0.163 | 48.7% | 0.001 |

| Inadequate prenatal careb | (3) (11) (6) (14) (16) (18) | 41,825 | 2.182 | [1.761–2.703] | 0.771 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Absence of prenatal careb | (14) (17) | 32,734 | 6.799 | [1.534–30.147] | 0.030 | 78.8% | 0.012 |

| Presence of complications during pregnancyb | (3) (14) | 24,788 | 6.961 | [4.979–9.733] | 0.381 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Birth weight between 1500 and 2499g | (3) (17)a(13) | 195,011 | 5.424 | [4.128–7.126] | 0.902 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Birth weight<1500gb | (3) (17)a(13) | 195,011 | 39.995 | [29.026–55.109] | 0.603 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Birth weight<2500gb | (12)a (3) (6)a(14) (15) (16) (18) | 18,239 | 15.519 | [9.997–24.092] | 0.684 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Presence of congenital malformationb | (3) (13) (15) (16) | 179,007 | 14.025 | [10.849–18.132] | 0.402 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Presence of Apgar score<7 at the 5th minuteb | (3) (13) (16) | 178,615 | 12.397 | [9.545–16.102] | 0.417 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Gestational age<37 weeksb | (12) (11)a(14) (13)a(16) (18)a | 155,846 | 7.130 | [4.329–11.742] | 0.706 | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Caesarean deliveryb | (17)a(13) (18) | 171,036 | 1.551 | [1.202–2.000] | 0.480 | 0.0% | 0.001 |

The study showed that factors related to the mother (absence of partner, age≥35 years, multiple pregnancy, absence or inadequacy of prenatal care, presence of complications during gestation, and Caesarean delivery) and to the newborn (male gender, congenital malformation, perinatal asphyxia, low birth weight, and prematurity) are risks associated to neonatal mortality in Brazil.

The main factor to be considered in this context is low birth weight and, more precisely, very low birth weight. In a prospective cohort study, in which neonatal mortality was analyzed in very low birth weight preterm infants in northeastern Brazil, it was observed that 76% died within the first 24h of life.19 This fact was also observed in another prospective cohort carried out in Brazil, based on the analysis of births in 20 public university centres, which resulted in a death rate of 30%,20 thus showing that low birth weight is a determinant factor in the occurrence of neonatal mortality in Brazil, representing its main isolated predictor.3,6,11–19,21–23 Low birth weight is considered one of the main risk factors for neonatal mortality in numerous locations and services, as observed in the studies carried out in Mexico,24 Jordan,25 Trinidad & Tobago,26 the United States,27 and China.28

Similarly to low birth weight, other factors are modifiable, such as perinatal asphyxia, prematurity, complications during pregnancy, prenatal care, caesarean delivery, older maternal age, and absence of a partner at home.3,6,11,14,17,19,21,22,29–33 In this context, it is worth highlighting the prenatal care, which, when properly performed, contributes to the reduction of other modifiable factors, mainly prematurity and low birth weight.3,6,11,14,16–18 This importance can be verified in a cross-sectional study carried out in a municipality in the Southeast region of Brazil, which showed that 26.8% of the deaths could have been prevented if an adequate prenatal care had been performed.34 A similar example can be found in another cross-sectional study conducted in several municipalities in a state in the Brazilian Southeast region, which showed that 47% of deaths could have been prevented through the implementation of early prevention, diagnosis, and treatment actions.35 These rates indicate problems in the care given to the pregnant woman, due to the lack of professional qualification or a deficient structure.21,32,33,36–39

As with prenatal care, caesarean delivery, if correctly indicated, reduces the occurrence of prematurity, low birth weight, and perinatal asphyxia.3,6,7,11–18 One of the big problems is the incorrect indication and excessive number of this type of delivery. The rate of caesarean deliveries in Brazil is 56%, well above the recommended rate, which is 15%.40 In a multicenter, observational, hospital-based study carried out in the Northeast region of Brazil, it was observed that 13.7% of neonatal deaths were related to caesarean delivery in high-risk neonatal units.41

Congenital malformation, multiple pregnancy, and the newborn's male gender were found to be determinants of neonatal mortality in Brazil in the present study, but they are not modifiable factors.3,6,7,11–18,32 Of these, congenital malformation is the most important factor, being the second most decisive factor for neonatal mortality in Brazil. A cross-sectional observational study carried out in several municipalities of a state in the Brazilian Southeast region showed that 42.8% of infant deaths were caused by this factor.35 The same trend can be observed in a prospective cohort carried out in a Mexican city, which showed in a neonatal mortality rate of 32%.24

The knowledge of risk factors is essential for the prevention of neonatal mortality in Brazil, since health professionals and managers, when aware of these conditions, can find ways to prevent clinical and structural complications.21,32,33,36–39 Thus, prevention consists of training professionals and providing adequate structure for the birth, as well as offering an individualized care to the pregnancies, paying individualized attention to the pregnancies, while taking into account the specificity of each condition.32,33,38,39 This individualization has become worldwide trend since 2015,42 which has resulted in a 5.4% reduction in global neonatal deaths between 2015 and 2017.43

The present study consisted of six articles with low bias risk and four articles with intermediate-low bias risk, thus increasing the degree of reliability of this study. The reason for the intermediate classification is due to the non-randomization of the interviewers in three studies, in addition to the inequality between the losses of the case and control groups in another study. The former can be solved by performing randomization and ensuring blind data collection, while equality of losses between groups would solve the second impasse.

The cohort studies were able to equally represent the population, in addition to matching the control group in an equivalent manner. One of the studies3 used a structured interview, differing from the other three,13,16,17 which used data from official databases. Regarding the final evaluation, all of them used linkage analysis with the official databases, in addition to establishing a sufficient follow-up period for the analysis. During follow-up, one of the studies17 showed a loss of less than 10% of the individuals, differing from the other studies, which did not show any loss.

The case–control studies, in turn, used linkage to the official database to adapt and represent cases, as well as to select and define controls. At the final evaluation, three studies14,15,18 used linkage analysis with data from official databases, while the other three6,11,12 performed interviews without the blinding procedure. One of the studies14 showed an unequal loss between the case and control groups, but because it was less than 10%, the final effect was not harmed. However, despite this statistical effect, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale does not score this fact in the case–control studies. In relation to the other studies, the rates were the same in both groups.

The overall result of this study shows the importance of these risk factors for neonatal mortality in Brazil, highlighting, in this context, the power that structural, behavioural, and medical changes have in reducing these rates.

The most significant risk factors shown in this study are modifiable, making it possible to achieve a real reduction in neonatal deaths, which remain high in Brazil.

FundingThis work was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (No. 129015/2017-2).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Veloso FC, Kassar LM, Oliveira MJ, Lima TH, Bueno NB, Gurgel RQ, et al. Analysis of neonatal mortality risk factors in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95:519–30.

Study conducted at Universidade Estadual de Ciências da Saúde de Alagoas, Maceió, AL, Brazil.