To determine the prevalence of neonatal dermatological findings and analyze whether there is an association between these findings and neonatal and pregnancy characteristics and seasonality.

MethodsNewborns from three maternity hospitals in a Brazilian capital city were randomly selected to undergo dermatological assessment by dermatologists.

Results2938 neonates aged up to three days of life were randomly selected, of whom 309 were excluded due to Intensive Care Unit admission. Of the 2530 assessed neonates, 49.6% were Caucasians, 50.5% were males, 57.6% were born by vaginal delivery, and 92.5% of the mothers received prenatal care. Some dermatological finding was observed in 95.8% of neonates; of these, 88.6% had transient neonatal skin conditions, 42.6% had congenital birthmarks, 26.8% had some benign neonatal pustulosis, 2% had lesions secondary to trauma (including scratches), 0.5% had skin malformations, and 0.1% had an infectious disease. The most prevalent dermatological findings were: lanugo, which was observed in 38.9% of the newborns, sebaceous hyperplasia (35%), dermal melanocytosis (24.61%), skin desquamation (23.3%), erythema toxicum neonatorum (23%), salmon patch (20.4%), skin erythema (19%), genital hyperpigmentation (18.4%), eyelid edema (17.4%), milia (17.3%), genital hypertrophy (12%), and skin xerosis (10.9%).

ConclusionsDermatological findings are frequent during the first days of life and some of them characterize the newborn's skin. Mixed-race newborns and those whose mothers had some gestational risk factor had more dermatological findings. The gestational age, newborn's ethnicity, gender, Apgar at the first and fifth minutes of life, type of delivery, and seasonality influenced the presence of specific neonatal dermatological findings.

Verificar a prevalência dos achados dermatológicos nos primeiros dias de vida e analisar se há associação com características neonatais, gestacionais e sazonalidade.

MétodosRecém-nascidos de três maternidades de uma capital brasileira foram selecionados aleatoriamente para serem submetidos ao exame dermatológico realizado por dermatologistas.

ResultadosForam selecionados aleatoriamente 2839 neonatos com até 72 horas de vida, 309 foram excluídos por terem sido admitidos em Unidade de Tratamento Intensivo. Dos 2530 neonatos examinados 49,6% eram da raça branca e 50,5% do sexo masculino. Foi observado algum achado dermatológico em 95,8% dos recém-nascidos; destes, 88,6% tinham lesões cutâneas transitórias neonatal, 42,6% marca de nascimento, 26,8% tinham pustulose benigna neonatal, 2% lesões secundárias ao trauma, 0,5% malformação cutânea e 0,1% doença infecciosa. O achado dermatológico mais frequente foi o lanugo, que foi observado em 38,9% dos neonatos, seguido pela hiperplasia de glândulas sebáceas (35%), melanocitose dérmica (24,6%), descamação da pele (23,3%), eritema tóxico neonatal (23%), mancha salmão (20,4%), eritema da pele (19%), hiperpigmentação da genitália (18,4%), edema palpebral (17,4%), cistos de mília (17,3%), hipertrofia da genitália (12%) e xerose cutânea (10,9%).

ConclusõesOs achados dermatológicos são frequentemente identificados nos primeiros dias de vida e muitos deles caracterizam a pele do recém-nascido. Os neonatos pardos e aqueles cujas mães apresentavam algum fator de risco gestacional tiveram mais achados dermatológicos. A idade gestacional, a etnia do neonato, o gênero, o índice de Apgar, o tipo de parto e a sazonalidade influenciaram na presença de manifestações cutâneas específicas.

The neonatal period is a time of adjustment when pathological and physiological reactions are often confused; skin changes are common in this period.1–4 Some authors report that 57–99.4% of newborns (NB) have some type of skin alteration and 84% have more than one dermatological finding.3,5,6 The frequency of these events differs between different racial groups.1,3

Most of these lesions are transient and specific to the neonatal period, such as lanugo, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, and skin desquamation.5 Birthmarks, such as salmon patch and dermal melanocytosis, are usually identified soon after birth, largely resulting from the newborn skin maturation or deepening of skin pigmentation over time.2 Cases of neonatal benign pustulosis, which are usually observed within the first weeks of life, include erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN), transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM), and benign cephalic pustulosis (BCP).7–9 Regarding the developmental abnormalities that occur in the skin and can be observed in the neonatal period, the most frequent are: aplasia cutis, fistulas and cysts, supernumerary nipple, and perimamillar adnexal polyp.10 Moreover, the introduction of new technologies and approaches in newborn care, in addition to skin fragility at this age, cause skin complications to be more frequently observed.11

Studies to estimate the frequency of skin disorders in newborns have been performed in several countries; however, this subject has been scarcely studied in Brazil. Thus, the present study aimed to increase medical knowledge on neonate skin characteristics, as well as to associate them with neonatal, pregnancy, and seasonality factors.

Materials and methodsThis was a prospective, multicenter study carried out in the following maternity hospitals in Porto Alegre, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil: Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Complexo Hospitalar Santa Casa de Porto Alegre, and Hospital Fêmina – Grupo Hospitalar Conceição (GHC), from July 2011 to June 2012. The newborns were randomly selected for the study according to the date of birth; the Pepi4-Random – Procedures using Random Numbers program, version 4.0 (WINPEPI, PEPI-for-Windows, NY, USA), was used to randomize eight monthly dates for one year. The study included all neonates born on the days randomized for data collection, whose tutors or parents agreed to participate and signed the informed consent form. Neonates admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) were excluded from the study analysis.

Dermatological assessment was performed by dermatologists with standardized training and with the help of dermatoscopy. The re-assessments were carried out in the Clinical Research Center of HCPA. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the three institutions where it was performed: HCPA – Project 1101013; Hospital Santa Casa de Porto Alegre – Protocol 3513/1, and Hospital Fêmina – Project 11-065.

Dermatological findings were classified as transient neonatal skin lesions, birthmarks, benign neonatal pustulosis, hemangioma or hemangioma precursors, lesions secondary to trauma, skin malformation, and infectious disease.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS v.20.0 program (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. NY, USA). Categorical variables were described by frequencies and percentages, and the prevalence by the 95% confidence intervals. In the secondary analysis of data, categorical variables were associated with each other using the chi-squared test, and the quantitative variables were compared by the Student's t-test for independent samples. A multivariable Poisson regression with robust variance was performed to evaluate possible associations between different study factors and lesions and to adjust for potential confounders. The significance level was set between 2% and 5%.

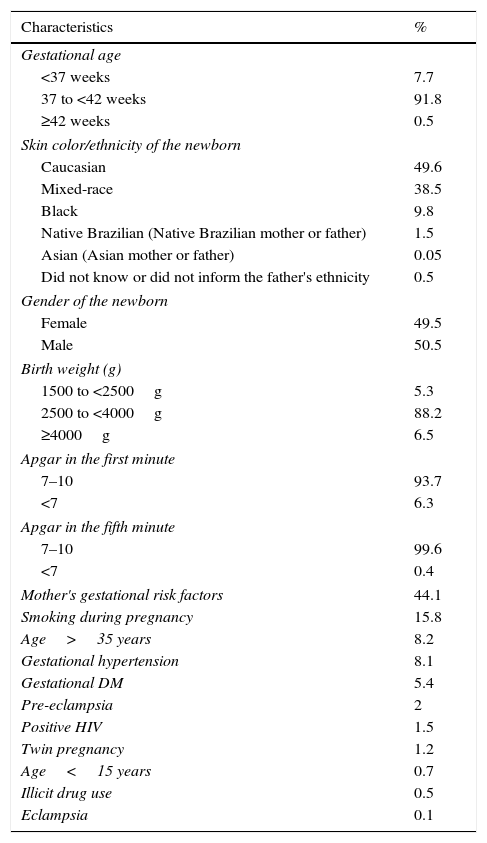

ResultsOf the 2839 newborns selected to participate in the study, 309 were excluded for having been admitted to the ICU. The mean gestational age was 38.41 weeks (median 39; 25–50 and 75 percentiles: 38–39 and 40, respectively); the predominant ethnicity was Caucasian; and 57.6% were born by vaginal delivery. Regarding the mothers, 92.5% received prenatal care, 59.8% were multiparous, and 44.1% had some gestational risk factor (GRF). Table 1 shows the neonatal characteristics and the GRFs.

Characteristics of newborns without admission to the NICU and gestational risk factors in maternity hospitals of Porto Alegre.

| Characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Gestational age | |

| <37 weeks | 7.7 |

| 37 to <42 weeks | 91.8 |

| ≥42 weeks | 0.5 |

| Skin color/ethnicity of the newborn | |

| Caucasian | 49.6 |

| Mixed-race | 38.5 |

| Black | 9.8 |

| Native Brazilian (Native Brazilian mother or father) | 1.5 |

| Asian (Asian mother or father) | 0.05 |

| Did not know or did not inform the father's ethnicity | 0.5 |

| Gender of the newborn | |

| Female | 49.5 |

| Male | 50.5 |

| Birth weight (g) | |

| 1500 to <2500g | 5.3 |

| 2500 to <4000g | 88.2 |

| ≥4000g | 6.5 |

| Apgar in the first minute | |

| 7–10 | 93.7 |

| <7 | 6.3 |

| Apgar in the fifth minute | |

| 7–10 | 99.6 |

| <7 | 0.4 |

| Mother's gestational risk factors | 44.1 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 15.8 |

| Age>35 years | 8.2 |

| Gestational hypertension | 8.1 |

| Gestational DM | 5.4 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 2 |

| Positive HIV | 1.5 |

| Twin pregnancy | 1.2 |

| Age<15 years | 0.7 |

| Illicit drug use | 0.5 |

| Eclampsia | 0.1 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

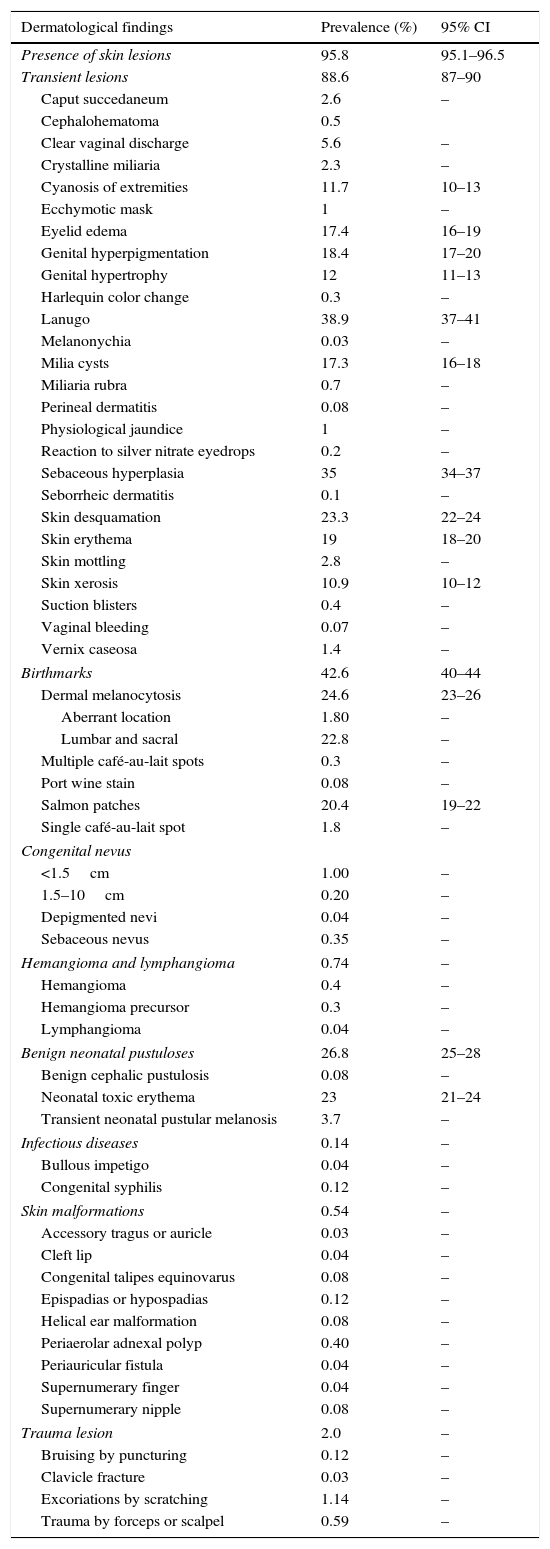

Of the assessed newborns, 95.8% had some dermatological finding. Of these, 88.6% had some transient neonatal skin manifestations, 42.6% had birthmarks, 26.8% had neonatal benign pustulosis, 2% had some skin lesions secondary to trauma, 0.5% had skin malformation, and 0.1% had an infectious disease (Table 2). A mean of 3.23 dermatological findings was observed per neonate with some type of skin manifestation.

Prevalence of dermatological findings of newborns without admission to the neonatal intensive care unit in maternity hospitals of Porto Alegre.

| Dermatological findings | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of skin lesions | 95.8 | 95.1–96.5 |

| Transient lesions | 88.6 | 87–90 |

| Caput succedaneum | 2.6 | – |

| Cephalohematoma | 0.5 | |

| Clear vaginal discharge | 5.6 | – |

| Crystalline miliaria | 2.3 | – |

| Cyanosis of extremities | 11.7 | 10–13 |

| Ecchymotic mask | 1 | – |

| Eyelid edema | 17.4 | 16–19 |

| Genital hyperpigmentation | 18.4 | 17–20 |

| Genital hypertrophy | 12 | 11–13 |

| Harlequin color change | 0.3 | – |

| Lanugo | 38.9 | 37–41 |

| Melanonychia | 0.03 | – |

| Milia cysts | 17.3 | 16–18 |

| Miliaria rubra | 0.7 | – |

| Perineal dermatitis | 0.08 | – |

| Physiological jaundice | 1 | – |

| Reaction to silver nitrate eyedrops | 0.2 | – |

| Sebaceous hyperplasia | 35 | 34–37 |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 0.1 | – |

| Skin desquamation | 23.3 | 22–24 |

| Skin erythema | 19 | 18–20 |

| Skin mottling | 2.8 | – |

| Skin xerosis | 10.9 | 10–12 |

| Suction blisters | 0.4 | – |

| Vaginal bleeding | 0.07 | – |

| Vernix caseosa | 1.4 | – |

| Birthmarks | 42.6 | 40–44 |

| Dermal melanocytosis | 24.6 | 23–26 |

| Aberrant location | 1.80 | – |

| Lumbar and sacral | 22.8 | – |

| Multiple café-au-lait spots | 0.3 | – |

| Port wine stain | 0.08 | – |

| Salmon patches | 20.4 | 19–22 |

| Single café-au-lait spot | 1.8 | – |

| Congenital nevus | ||

| <1.5cm | 1.00 | – |

| 1.5–10cm | 0.20 | – |

| Depigmented nevi | 0.04 | – |

| Sebaceous nevus | 0.35 | – |

| Hemangioma and lymphangioma | 0.74 | – |

| Hemangioma | 0.4 | – |

| Hemangioma precursor | 0.3 | – |

| Lymphangioma | 0.04 | – |

| Benign neonatal pustuloses | 26.8 | 25–28 |

| Benign cephalic pustulosis | 0.08 | – |

| Neonatal toxic erythema | 23 | 21–24 |

| Transient neonatal pustular melanosis | 3.7 | – |

| Infectious diseases | 0.14 | – |

| Bullous impetigo | 0.04 | – |

| Congenital syphilis | 0.12 | – |

| Skin malformations | 0.54 | – |

| Accessory tragus or auricle | 0.03 | – |

| Cleft lip | 0.04 | – |

| Congenital talipes equinovarus | 0.08 | – |

| Epispadias or hypospadias | 0.12 | – |

| Helical ear malformation | 0.08 | – |

| Periaerolar adnexal polyp | 0.40 | – |

| Periauricular fistula | 0.04 | – |

| Supernumerary finger | 0.04 | – |

| Supernumerary nipple | 0.08 | – |

| Trauma lesion | 2.0 | – |

| Bruising by puncturing | 0.12 | – |

| Clavicle fracture | 0.03 | – |

| Excoriations by scratching | 1.14 | – |

| Trauma by forceps or scalpel | 0.59 | – |

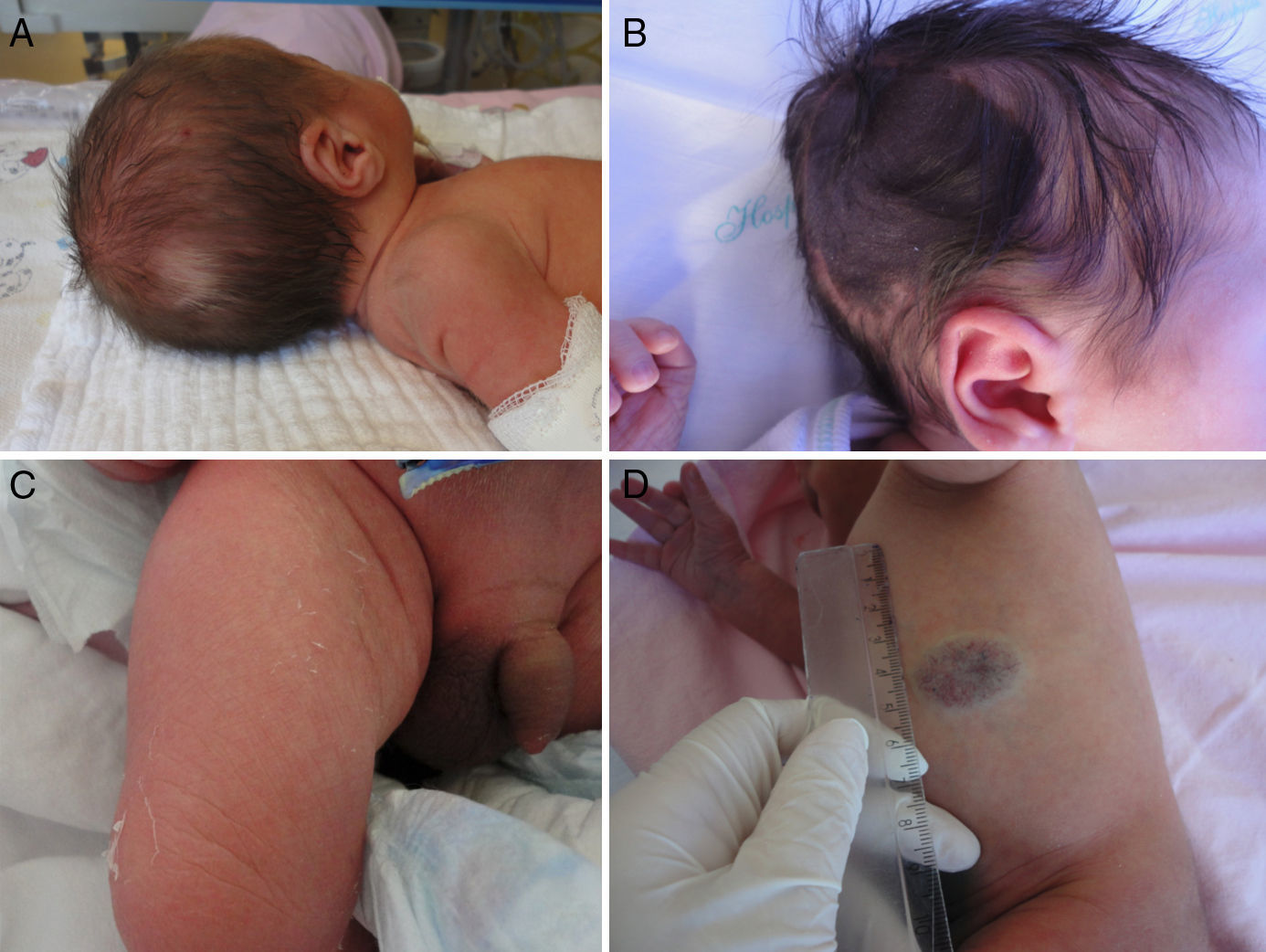

The most common dermatological finding was lanugo, found in 38.9% of infants, followed by sebaceous hyperplasia (35%), dermal melanocytosis (24.6%), skin desquamation (23.3%), ETN (23%), salmon patch (20.4%), skin erythema (19%), genital hyperpigmentation (18.4%), eyelid edema (17.4%), milia cysts (17.3%), genital hypertrophy (12%), cyanosis of the extremities (11.7%), and skin xerosis (10.9%) (Figs. 1 and 2).

It was also observed a prevalence of 3.7% of TNPM; 2.8% of skin mottling; 2.6% of caput succedaneum; 2.3 of miliaria crystalline; 1.8% single café au lait spot and aberrant dermal melanocytosis; 1.4% of vernix caseosa; 1.2% of congenital nevus; 1% of ecchymotic mask and 0.1% of hematoma by puncture; 0.74% of hemangioma or hemangioma precursor; 0.7% of miliaria rubra, 0.5% of cephalohematoma; 0.4% of perimamillar adnexal polyp; and 0.3% of sebaceous nevus, suction blisters, and Harlequin color change. It was observed a prevalence of 0.14% of infectious diseases, which corresponded to three cases of congenital syphilis and one case of bullous impetigo.

A higher prevalence of lanugo was observed in preterm newborns (p<0.001). The full-term infants had more benign neonatal pustuloses and milia cysts (p<0.001), whereas post-term newborns had a higher prevalence of transient skin lesions (p=0.001), such as genital hyperpigmentation (p=0.001) and skin xerosis (p=0.02), as well as birthmarks (p<0.001), such as Mongolian spots and salmon patches (p<0.001). ETN was positively associated with gestational age (p<0.001).

Regarding the newborn's ethnicity, it was observed that Caucasian newborns had a higher prevalence of ETN (p<0.001), as well as some transitional lesions, such as milia cysts (p=0.005), skin erythema (p<0.001), sebaceous hyperplasia (p=0.005), and salmon patches (p=0.017). Black newborns showed a higher prevalence of Mongolian spots, skin desquamation in the extremities, genital hyperpigmentation, and xerosis (p<0.001). In mixed-race newborns, transient skin findings had a higher prevalence (p<0.001), such as genital hypertrophy (p<0.001). As for gender, it was observed that female newborns had a higher prevalence of transient findings (p=0.026), whereas males had a higher prevalence of ETN (p=0.002) and genital hyperpigmentation (p<0.001).

Regarding the Apgar in the first minute of life, a higher prevalence of ETN was observed in neonates with Apgar score between 8 and 10 (p<0.001); as for the Apgar score at 5min of life, neonates with Apgar between 0 and 3 had a higher prevalence of lanugo.

The type of delivery also influenced the presence of some dermatological findings. Neonates born by vaginal delivery had a higher prevalence of genital hyperpigmentation (p<0.001) and genital hypertrophy (p=0.011), as well as of birthmarks (p<0.001). Those born by assisted vaginal delivery had more skin desquamation (p=0.048), desquamation of the extremities (p=0.002), and palpebral edema and erythema (p<0.001). Vaginal delivery was performed more frequently in infants weighing between 2500 and 3999g and in full-term or post-term newborns (p<0.001).

When evaluating the GFR, it was observed that neonates born to mothers with some risk factor had a higher prevalence of dermatological findings (p=0.047). This difference was also observed for transient neonatal lesions (p<0.001). The newborns of mothers with no risk factors had a higher prevalence of birthmarks (0.016) and ETN (p<0.001). Infants born to mothers who had gestational diabetes had more skin erythema (p=0.048) and lower prevalence of lanugo (p<0.001). When evaluating gestational hypertension, an increased prevalence of skin erythema (p=0.013) and genital hypertrophy (p=0.028) was noted. HIV positivity was observed in 1.7% of mothers, but no association was found with the presence of neonatal dermatological findings. Furthermore, maternal age did not influence the presence of neonatal dermatological findings.

Regarding the seasonality, it was observed that there were more transient lesions in summer (p=0.008), such as sebaceous hyperplasia (p=0.049) and xerosis (p<0.001). The prevalence of ETN was higher in the spring (p=0.004). The prevalence of eyelid edema (p=0.001) and skin erythema (p=0.001) was higher in the fall; in the winter months, skin desquamation (p<0.001) and genital hypertrophy (p<0.001) were more prevalent.

DiscussionSeveral authors have assessed the prevalence of neonatal dermatological findings in different countries. However, there is no homogeneity regarding the terminology and the design used in the studies, which makes the comparison between them difficult. No other authors evaluated the seasonality of neonatal dermatological findings, which this study did, for the first time. Despite the methodological differences between the studies, the prevalence of dermatological findings in newborns was similar to that described by other authors (90%). However, it was higher than that reported by authors in Turkey, who found a frequency of 67.3% of skin findings in 1234 newborns up to 48h of life.6

Physiological desquamation is observed in most newborns and it is usually more intense between the sixth and seventh days of life.12 The results of the present study differ from other published data, as the rate was lower than that reported by authors who assessed newborns within seven days of life,12 and higher than that reported by authors who evaluated newborns up to 48h of life.3 The authors believe that this difference was due to the fact that the dermatological examination was performed within the first 72h of life, during which this finding is usually less prevalent.

The prevalence of salmon patch was lower than that reported by some authors, who observed a prevalence of 26–83%,3,13,14 and similar to that reported by others, such as the study performed in Turkey, which observed a prevalence of 19.2%.15 The prevalence of dermal melanocytosis was higher than that described for Caucasian children, which was reported to occur in less than 10% of newborns,2,13 probably due to the miscegenation characteristics of the study population. Both the salmon patch and dermal melanocytosis showed a positive correlation with gestational age and, despite the small number of post-term newborns assessed in the present study, it may indicate that the birthmarks are a marker of skin maturity in the neonate. Moreover, the difference observed with data published by other authors may indicate that the population characteristics have an important influence on the presence of birthmarks.

The prevalence of milia cysts was similar to that found in Spanish newborns, of 16.6%16; however, it was higher than that reported by American authors, which was of 8%.13 Milia cysts were more prevalent in full-term neonates; they can also be an indicator of skin maturity.

A lower prevalence of vernix caseosa was observed when compared with that reported in Spanish newborns, 42.9%.16 The authors believe that this difference is due to the fact that most assessed newborns had already received the first bath, which in the maternity hospitals where the study was carried out usually occurs between 24 and 48h after birth.

A higher prevalence of benign neonatal pustuloses was observed in the first 48h of life than expected.17,18 The prevalence of ETN was similar to that reported in a prospective study carried out in Spain with 365 infants, which found a prevalence of 25.3%.19 However, it was observed that ETN occurred more often than expected for newborns within the first 48h of life when compared with a study performed in California, which showed a prevalence of 7% of ETN in neonates with up to 48h of life.13 Unlike the authors who reported that ETN was more prevalent in cesarean section deliveries4,6 and others who observed a higher prevalence of ETN in vaginal births,20 no differences between the type of delivery and frequency of ETN were observed in the present study. Furthermore, TNPM prevalence was higher than expected for a predominantly Caucasian population, probably due to the miscegenation characteristics of the study population. ETN was less prevalent in the winter months, similar to that reported by other authors who indicated that this condition is more common in hot and humid climates.21 It was also observed that ETN was more prevalent in infants born under optimal conditions and without GRF, which may indicate that this is a dermatological finding of healthy newborns.

Unlike other studies,20 no associations between prematurity and genital hyperpigmentation or cutis marmorata were observed. In contrast, a higher frequency of genital hyperpigmentation was observed in post-term newborns; this could also be an indicator of skin maturity. No association was found between the newborn's maturity and sebaceous hyperplasia and skin desquamation, as reported by other authors.16

The frequency of neonatal dermatological findings was higher in infants of mothers with GRF due to neonatal transitional lesions, which indicates that certain maternal comorbidities may influence the skin of newborns, such as diabetes and gestational hypertension, which were associated with skin erythema and gestational hypertension with genital hypertrophy. A higher prevalence of genital hypertrophy was also observed in newborns of mothers who had gestational hypertension. Other authors found an association between genital hypertrophy and gestational disease and medication use during pregnancy22; however, the drugs used during pregnancy were not evaluated in this study.

The prevalence of positive serology for HIV in pregnancy was higher than that expected for women of all ages in Brazil, which is 0.42%; it was higher than that reported by other authors for pregnant women between 15 and 24 years of age treated in Brazilian hospitals (0.7%),23 and it was also higher than that reported in pregnant women in other regions of Brazil.24,25 Although the prevalence of HIV positivity was high when compared to other regions of Brazil, this fact had no association with skin lesions.

The prevalence of infectious lesions in the present study was lower than that reported for newborns in neonatal ICUs (4%),16 probably because only neonates in rooming-in were included.

Regarding the seasonality of dermatological findings, the authors believe that the higher prevalence of sebaceous hyperplasia in the summer months may be due to increased glandular activity in the warmer months. ETN was more prevalent in the spring; as reported by other authors, its prevalence can be influenced by the climate.21 The colder humid weather characteristic of winter months may precipitate skin desquamation in neonates.

Dermatological findings are often identified in newborns, and many of them characterize the newborn's skin, which justifies a detailed dermatological examination.24 The skin findings most commonly observed in neonates are generally transient and result from the normal physiological responses. They are usually limited to the first days or weeks of life and, therefore, they are rarely evaluated by dermatologists. The correct identification of these findings is important to help to differentiate them from pathological findings, avoid unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, as well as decrease the concerns of parents and assistants.4

This multicenter study of data collected during one year in a city with well-defined seasons, using the appropriate dermatological nomenclature and with skin examinations performed by specialists, provided important data on the prevalence of dermatological findings in the first 72h of life, as well as the influence of ethnicity, GRF, and seasonality.

A high prevalence of neonatal dermatological findings was observed in the first 72h of life in the region where the study was performed, highlighting the importance of a detailed dermatological examination. The neonate's ethnicity and maternal gestational risk factors influenced the presence of dermatological findings. Furthermore, an association was observed between specific skin manifestations and certain neonatal characteristics, such as gestational age, ethnicity, gender, and Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes of life, as well as with gestational characteristics, such as the type of delivery. The most prevalent dermatological findings were also distinct in the different seasons in the year.

The differences in the prevalence of skin manifestations in comparison with other studies show that the population characteristics and the period during which the skin of the newborn was assessed may influence the presence of dermatological findings, but this association is not clear; more specific studies are necessary.

FundingThe study was funded by Fundo de Incentivo a Pesquisa do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Vânia Naomi Hirakata and Daniela Benzano for the high-quality statistical analysis of data in this article. The authors would also like to thank the physicians Ana Carolina Saraiva Camerin, Fabiana de Oliveira Bazanella, Kalyanna Gil Portal, Renata Rosa, Rodrigo Pizzoni, and Samanta Daiana De Rossi, for their crucial help to enter data into Excel spreadsheets. Finally, the authors would like to thank the medical and nursing staffs of the hospitals where the study was performed and especially the parents of newborns who allowed their newborns’ skin to be examined, enabling the performance of this study.

Please cite this article as: Reginatto FP, DeVilla D, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, Peres LP, Steglich RB, et al. Prevalence and characterization of neonatal skin disorders in the first 72h of life. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:238–45.

Study conducted at the Postgraduate Program in Child and Adolescent Health, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS); and at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.