To identify and assess the current evidence available about the costs of managing hospitalized pediatric patients diagnosed with Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 (PIV3) in upper-middle-income countries.

MethodsThe authors conducted a systematic review across seven key databases from database inception to July 2022. Costs extracted were converted into 2022 International Dollars using the Purchasing Power Parity-adjusted. PROSPERO identifier: CRD42020225757.

ResultsNo eligible study for PIV3 was recovered. For RSV, cost analysis and COI studies were performed for populations in Colombia, China, Malaysia, and Mexico. Comparing the total economic impact, the lowest cost per patient at the pediatric ward was observed in Malaysia ($ 347.60), while the highest was in Colombia ($ 709.66). On the other hand, at pediatric ICU, the lowest cost was observed in China ($ 1068.26), while the highest was in Mexico ($ 3815.56). Although there is no consensus on the major cost driver, all included studies described that the medications (treatment) consumed over 30% of the total cost. A high rate of inappropriate prescription drugs was observed.

ConclusionThe present study highlighted how RSV infection represents a substantial economic burden to health care systems and to society. The findings of the included studies suggest a possible association between baseline risk status and expenditures. Moreover, it was observed that an important amount of the cost is destinated to treatments that have no evidence or support in most clinical practice guidelines.

Respiratory viruses are the main cause of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) and hospitalization among infants and young children. Globally, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading infectious agent in this population, with over 30 million cases every year and up to 199,000 deaths per year.1 After RSV, parainfluenza virus (PIV) is the most prevalent cause of infection, accounting for 2% to 17% of LRTI cases, with PIV type 3 accounting for a substantial number of illnesses and hospitalization among children under six months old.2

The transmission of the viruses occurs mainly due to contact with contaminated surfaces and respiratory secretions. The seasonality of the infections varies according to the location, with outbreaks occurring annually, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Common symptoms include upper respiratory tract infection, such as nasal congestion, fever, cough, and rhinorrhea, or an LRTI, such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia. For RSV-associated illness, specifically, it may also be observed difficulty breathing, wheezing or apnea. In both infections, most cases are managed at the ambulatory level, with 1% to 3% of children needing admission to a general ward and less than 1% to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Overall, episodes requiring hospitalization are associated with underlying conditions, and acute and long-term complications.2-5

Besides the epidemiological impact, RSV and PIV3 infections have a significant economic burden on households, health systems, and national incomes. In general, the number of cases per total population, the complications associated and, consequently, the economic impact of the diseases are considerably lower in High-Income Countries (HIC). For Upper-Middle-Income Countries (UMIC), especially due to the larger proportion of infections (over 90% of RSV cases), limited access to hospital care and resource constriction, it is estimated a more significant economic burden.2,5

Economic studies are important tools to inform the planning of healthcare resources, evaluation of policy options, and prioritization of research. They describe the consumption and loss of resources as a result of a disease, together with an epidemiological overview. Overall, economic evaluations in health help to portray the impact of a clinical condition on society.2,5,6

Thus, the objective of this study was to identify and assess the current evidence available about the costs of managing hospitalized pediatric patients diagnosed with RSV and PIV3 in UMIC through a systematic review. The goal was to compare the cost of disease estimates between countries with a similar economic development level and appraise relevant cost drivers.

MethodsStudy design and registrationThe authors performed a systematic review following the Cochrane methodology with adaptations for inclusion and assessment of cost studies, as performed in previous investigations.6 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used as a basis for the overall study approach.7 The authors registered the protocol at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) [identifier: CRD42020225757], with a full-text publication prior to starting the literature search.8

Search strategyThe search strategy was developed by an information specialist. A combination of controlled vocabulary and keyword terms was used, including the following concepts: (i) RSV or PIV3; (ii) cost analysis; (iii) UMIC; and (iv) children. To obtain maximum coverage of the published and unpublished literature, the authors searched the databases PubMed, EMBASE, BVS Portal, CINAHL, CRD library, and the preprint platforms MedRxiv and Research Square. No filter of a year of publication or language was applied. In addition, the authors scooped the reference list of included studies.8 Records from all databases were searched on July 22, 2022 (see supplementary file for database queries and resulting yields).

Study selectionThe eligibility criteria focused on studies that generated partial economic evaluation, such as cost-of-illness (COI), from primary data collection. The authors included investigations that individually discussed the economic burden of RSV or PIV3 on pediatric individuals (<18 years old) in a UMIC. Although respiratory viruses are more prevalent in children under two years of age, the authors chose to include the whole pediatric range to assess how this variable may impact the burden of disease.5

For both viral infections, the authors considered the definitions of the World Health Organization, excluding articles that presented data on acute infections or specified etiology (e.g., pneumonia).8 To be considered an RSV disease, the study should report a laboratory diagnosis and clinical manifestations of bronchiolitis or pneumonia, with fever and possible progression to dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and/or crackles on chest auscultation. For PIV3-related Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI), the authors considered a valid diagnosis a virology investigation and clinical manifestations of bronchiolitis, bronchitis, or pneumonia, with fever, runny nose, and cough.8 For UMIC, the authors followed the classification of the World Bank (2019 GNI).9

Recovered studies from the search strategy were managed using the web-based bibliographic manager Rayyan QCRI.10 Duplicate records were removed, and first titles and then abstracts were screened by two reviewers independently (CRRF and GSR), masked for the decisions. After this step, the two researchers assessed the full text of records screened, to determine the final eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by the involvement of a third investigator (HS or LC).8

Data extractionData were extracted by one reviewer (CRRF), according to a standardized data extraction used in previous systematic reviews of cost analysis.6 All extracted data were double-checked by a second reviewer (GSR), and any variances were thoroughly discussed with a third researcher (VFMT). Costs extracted were converted into 2022 International Dollars (Int$ 2022) using the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)-adjusted proposed on the cost converter tool from CCEMG-EPPI Centre (https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/).11

Contact with the authors of the included study was necessary to solicit relevant information in case of insufficient data, such as price year considered, and cost components. When the base year of the currency could not be inferred due to no return or any impossibility within the contract, the authors assumed as reference year the year before the publication of the manuscript.8

Study assessmentCriteria to assess methodological strengths and weaknesses in study design were adapted from a previous costing review by Oliveira et al.,12 which was based on the protocol proposed by the British Medical Journal (BMJ), and on the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). All included studies were independently appraised by two reviewers (CRRF and JWLM). The results were confronted, and any discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer (RCL).

Data synthesisThe data extracted were stratified, synthesized, and narratively reported per inpatient care at pediatric wards or pediatric ICU. Based on the previous systematic review of cost analyses,6 the authors established four cost categories to identify dominant cost drivers: treatment, diagnosis, medical care, and daily cost, and others. When only the total cost per variable was presented, the authors calculated the individual value based on the population sample. The quality assessment analysis was plotted using the tool provided by McGuinness and Higgins.13

ResultsSearch resultsThe initial databases search yielded 376 references to systematically assess. After duplicate studies were removed, the titles and abstracts from 357 records were screened for inclusion. In the first moment, 15 reports were assessed for eligibility. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, six studies were selected for inclusion. One study was published twice in different journals.14,15 The authors included both manuscripts in the analysis but considered them as unique studies. Therefore, by the end, five unique studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review.14,16–19 A PRISMA Flow Diagram of the study selection and a list of excluded studies with a reason for exclusion are presented in supporting information.

Study characteristicsAll five studies appraised in this systematic review discussed the economic impact of RSV disease. From the search strategy, the authors could not identify any eligible study on PIV3 disease.

Cost data were obtained from four different countries, including Colombia, China, Malaysia, and Mexico. Most of the studies (n = 04) were retrospective cost analyses, and one was a COI study. Only the COI study adopted a societal perspective for costing, presenting a bottom-up and prevalence approach. The other studies performed a health facility perspective and did not report the resource quantification or epidemiological approach (see supplementary material for a summary of findings).

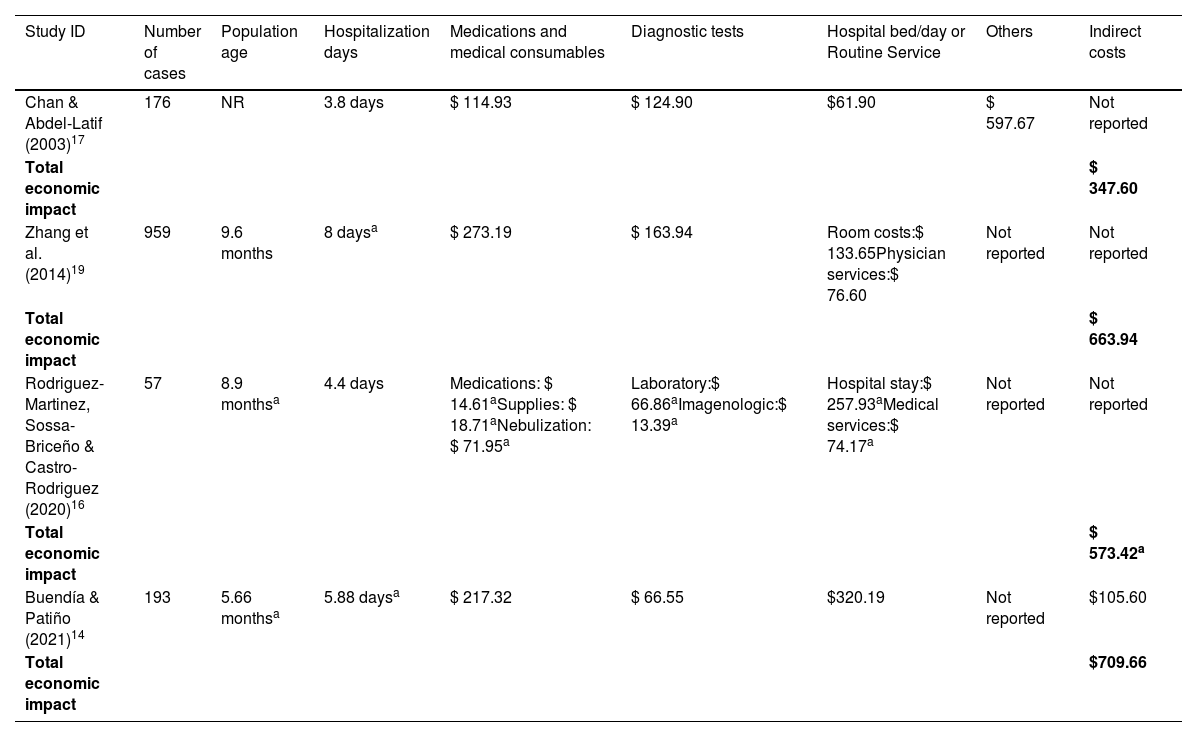

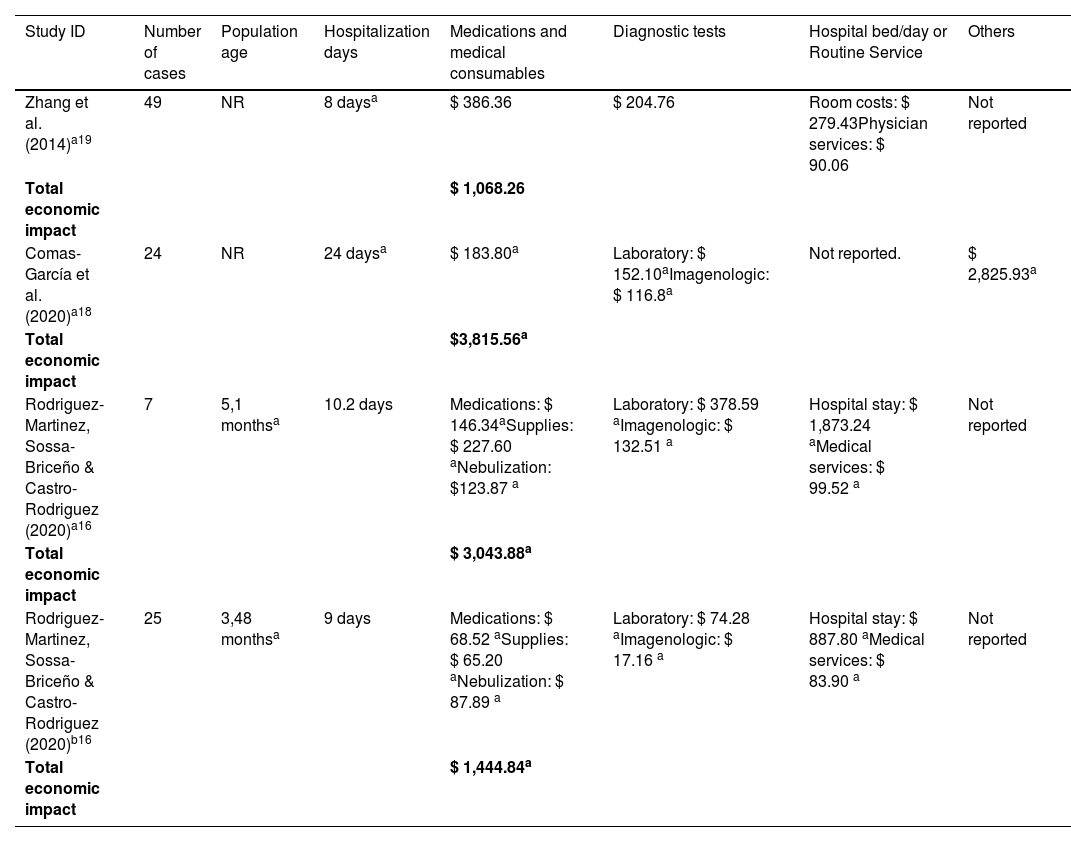

Inpatient care costs of RSVThe inpatient care costs of RSV are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, corresponding to economic impact at the pediatric ward, and at the pediatric ICU and Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit (PIMC), respectively. All studies included a population of children, with an overall age less than two years old. A total of 1481 RSV disease episodes were included in the cost analysis, including 1425 cases at the pediatric ward, 80 cases at the pediatric ICU, and 25 cases at PIMC.

Economic impact of inpatients with RSV at pediatric ward [ordered by year of publication.

| Study ID | Number of cases | Population age | Hospitalization days | Medications and medical consumables | Diagnostic tests | Hospital bed/day or Routine Service | Others | Indirect costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan & Abdel-Latif (2003)17 | 176 | NR | 3.8 days | $ 114.93 | $ 124.90 | $61.90 | $ 597.67 | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 347.60 | |||||||

| Zhang et al. (2014)19 | 959 | 9.6 months | 8 daysa | $ 273.19 | $ 163.94 | Room costs:$ 133.65Physician services:$ 76.60 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 663.94 | |||||||

| Rodriguez-Martinez, Sossa-Briceño & Castro-Rodriguez (2020)16 | 57 | 8.9 monthsa | 4.4 days | Medications: $ 14.61aSupplies: $ 18.71aNebulization: $ 71.95a | Laboratory:$ 66.86aImagenologic:$ 13.39a | Hospital stay:$ 257.93aMedical services:$ 74.17a | Not reported | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 573.42a | |||||||

| Buendía & Patiño (2021)14 | 193 | 5.66 monthsa | 5.88 daysa | $ 217.32 | $ 66.55 | $320.19 | Not reported | $105.60 |

| Total economic impact | $709.66 |

Costs were adjusted into Int$2022. See the supplementary file for a description of cost categories components.

Data are presented as mean per patient, except for a which are presented as median per patient. NR: not reported.

Economic impact of inpatients with RSV at pediatric ICU and PIMC [ordered by year of publication.

| Study ID | Number of cases | Population age | Hospitalization days | Medications and medical consumables | Diagnostic tests | Hospital bed/day or Routine Service | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. (2014)a19 | 49 | NR | 8 daysa | $ 386.36 | $ 204.76 | Room costs: $ 279.43Physician services: $ 90.06 | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 1,068.26 | ||||||

| Comas-García et al. (2020)a18 | 24 | NR | 24 daysa | $ 183.80a | Laboratory: $ 152.10aImagenologic: $ 116.8a | Not reported. | $ 2,825.93a |

| Total economic impact | $3,815.56a | ||||||

| Rodriguez-Martinez, Sossa-Briceño & Castro-Rodriguez (2020)a16 | 7 | 5,1 monthsa | 10.2 days | Medications: $ 146.34aSupplies: $ 227.60 aNebulization: $123.87 a | Laboratory: $ 378.59 aImagenologic: $ 132.51 a | Hospital stay: $ 1,873.24 aMedical services: $ 99.52 a | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 3,043.88a | ||||||

| Rodriguez-Martinez, Sossa-Briceño & Castro-Rodriguez (2020)b16 | 25 | 3,48 monthsa | 9 days | Medications: $ 68.52 aSupplies: $ 65.20 aNebulization: $ 87.89 a | Laboratory: $ 74.28 aImagenologic: $ 17.16 a | Hospital stay: $ 887.80 aMedical services: $ 83.90 a | Not reported |

| Total economic impact | $ 1,444.84a |

Costs were adjusted into Int$2022. See supplementary file for a description of cost categories components. Data are presented as mean per patient, except for a which are presented as median per patient. No study reported costs for the category “indirect costs.”

Rodriguez-Martinez et al.16 described that the admission criteria to the PIMC include patients that present worsening hypoxemia or hypercapnia, worsening respiratory distress, continuing requirement for more than 50% oxygen, hemodynamic instability, altered mental state, or apnea. Chan and Abdel-Latif17 did not present individual costs for pediatric ICU, encompassing the burden of this population in the cost component “others”. A detailed presentation of the cost categories components reported in the included studies can be found in Table 3.

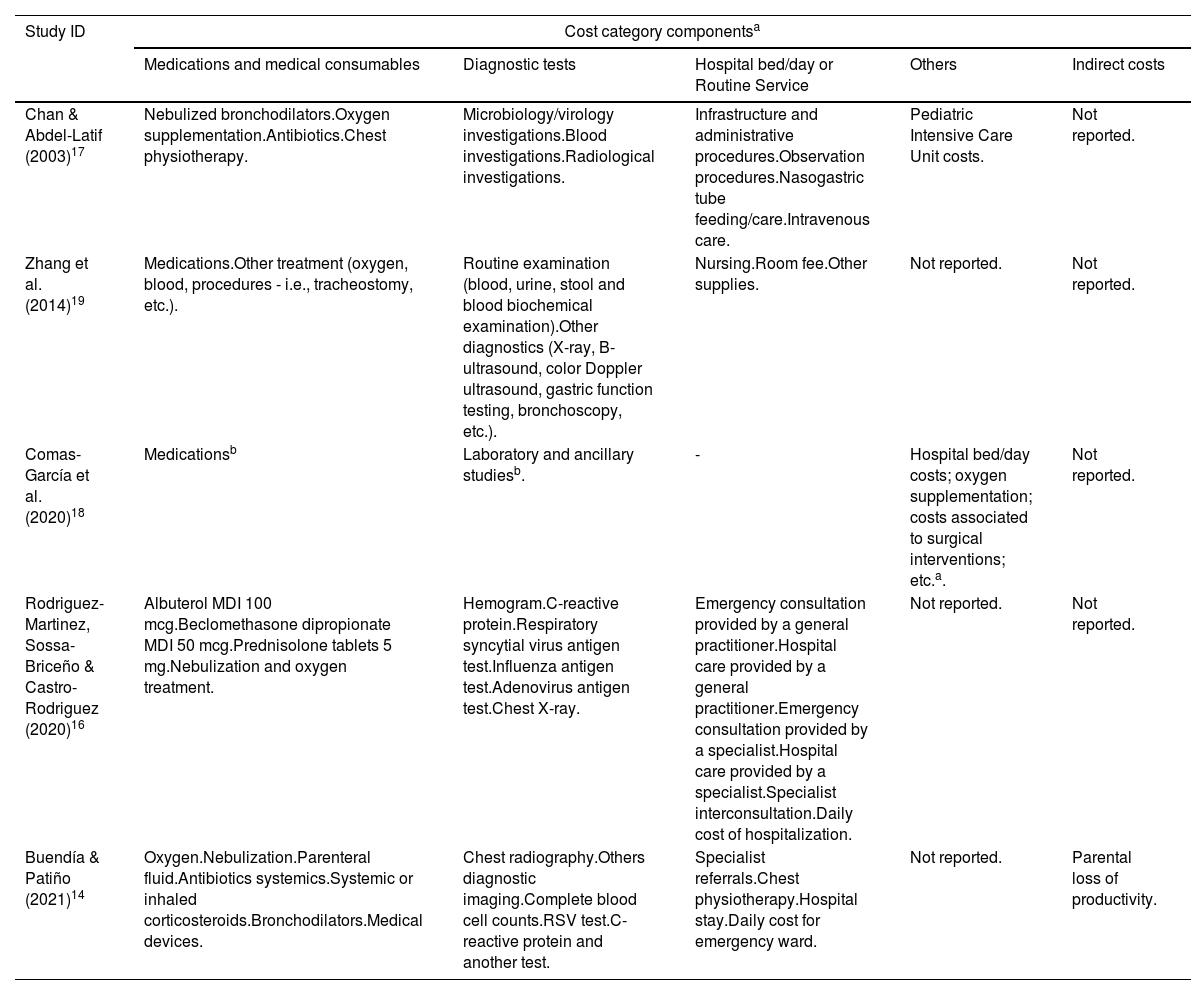

Cost categories components reported in the included studies [ordered by year of publication.

| Study ID | Cost category componentsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications and medical consumables | Diagnostic tests | Hospital bed/day or Routine Service | Others | Indirect costs | |

| Chan & Abdel-Latif (2003)17 | Nebulized bronchodilators.Oxygen supplementation.Antibiotics.Chest physiotherapy. | Microbiology/virology investigations.Blood investigations.Radiological investigations. | Infrastructure and administrative procedures.Observation procedures.Nasogastric tube feeding/care.Intravenous care. | Pediatric Intensive Care Unit costs. | Not reported. |

| Zhang et al. (2014)19 | Medications.Other treatment (oxygen, blood, procedures - i.e., tracheostomy, etc.). | Routine examination (blood, urine, stool and blood biochemical examination).Other diagnostics (X-ray, B-ultrasound, color Doppler ultrasound, gastric function testing, bronchoscopy, etc.). | Nursing.Room fee.Other supplies. | Not reported. | Not reported. |

| Comas-García et al. (2020)18 | Medicationsb | Laboratory and ancillary studiesb. | - | Hospital bed/day costs; oxygen supplementation; costs associated to surgical interventions; etc.a. | Not reported. |

| Rodriguez-Martinez, Sossa-Briceño & Castro-Rodriguez (2020)16 | Albuterol MDI 100 mcg.Beclomethasone dipropionate MDI 50 mcg.Prednisolone tablets 5 mg.Nebulization and oxygen treatment. | Hemogram.C-reactive protein.Respiratory syncytial virus antigen test.Influenza antigen test.Adenovirus antigen test.Chest X-ray. | Emergency consultation provided by a general practitioner.Hospital care provided by a general practitioner.Emergency consultation provided by a specialist.Hospital care provided by a specialist.Specialist interconsultation.Daily cost of hospitalization. | Not reported. | Not reported. |

| Buendía & Patiño (2021)14 | Oxygen.Nebulization.Parenteral fluid.Antibiotics systemics.Systemic or inhaled corticosteroids.Bronchodilators.Medical devices. | Chest radiography.Others diagnostic imaging.Complete blood cell counts.RSV test.C-reactive protein and another test. | Specialist referrals.Chest physiotherapy.Hospital stay.Daily cost for emergency ward. | Not reported. | Parental loss of productivity. |

Three pieces of evidence observed that basal characteristics, such as age and comorbidities, are important factors in an escalation of hospitalization costs. Overall, it was reported that children over six months old or with underlying illnesses had longer lengths of stay and more chances to be admitted to ICU.15,17,19

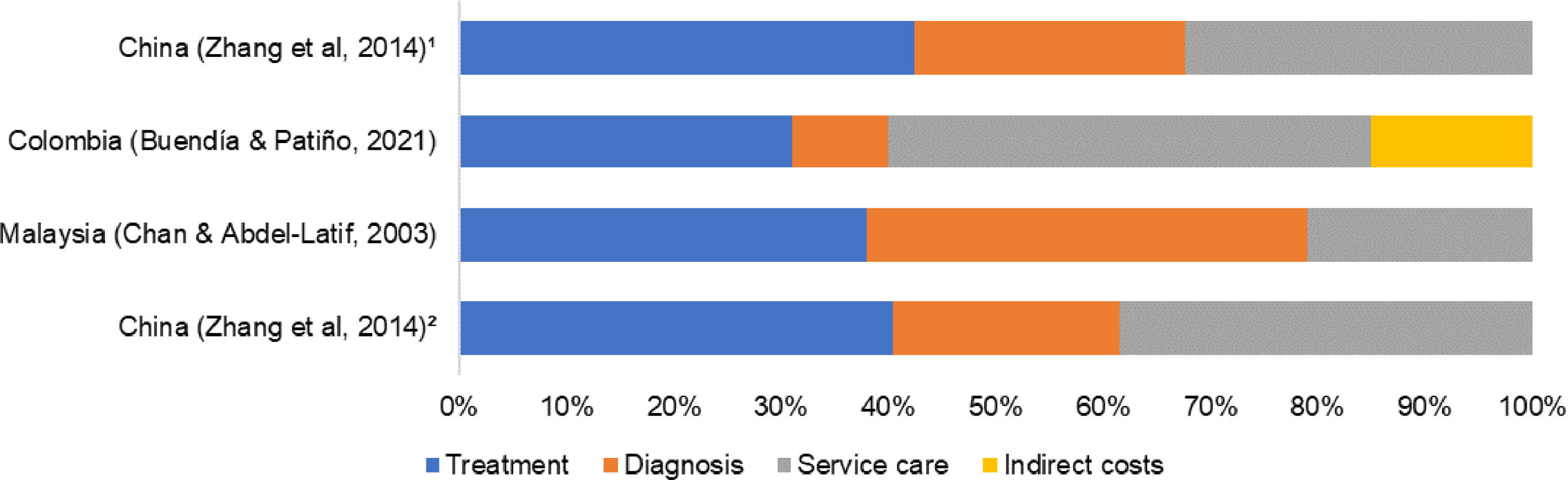

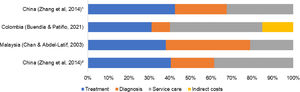

Cost driversFigure 1 presents the percentage of consumption of total cost for the four cost categories: treatment, diagnosis, service care, and others. The studies that presented data as median16,18 were excluded.

Overall, there was no agreement between included studies about the most dominant cost driver. At the pediatric ward, Zhang et al.19 reported medications and medical consumables as the dominant cost drivers, consuming over 40% of the total cost. On the other hand, Chan and Abdel-Latif17 appointed the diagnosis category as the dominant cost driver (41%), while Buendía and Patiño14 appointed the hospital bed/day or routine service costs category (45%).

At pediatric ICU, only the study of Zhang et al.19 was included. The most dominant cost driver was the medications and medical consumables category, consuming over 42% of total costs.

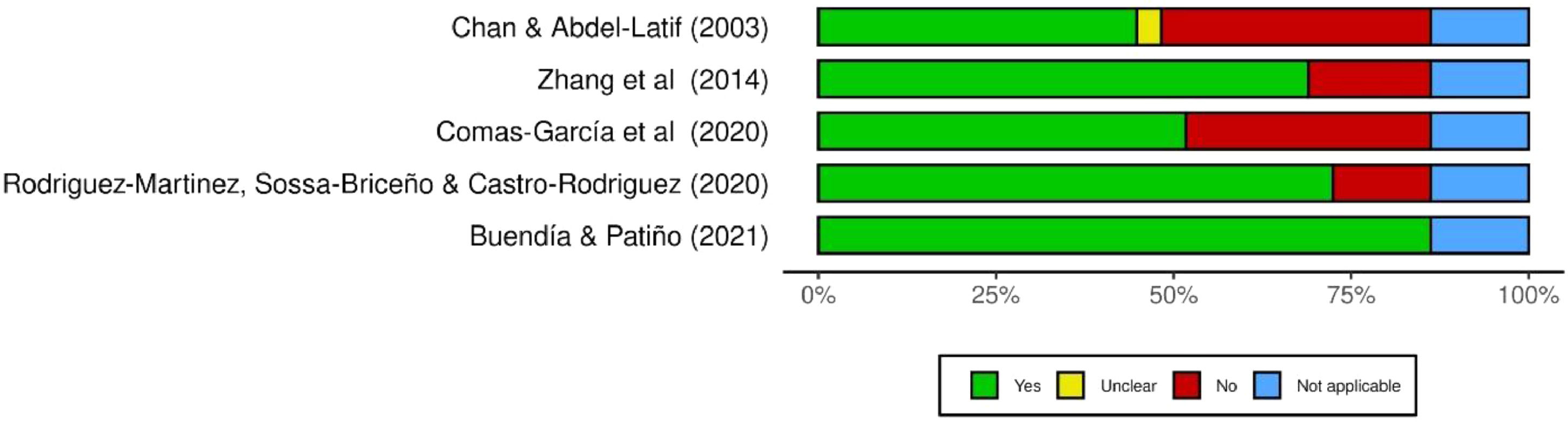

Report assessment of the included studiesA summary plot of the methodology assessment of included studies is presented in Figure 2. Overall, most of the studies (n = 04) satisfactorily reported their methodology and results (more than 60% of “yes” answers).12 A traffic-light plot with a detailed assessment per question is presented in supporting information.

DiscussionThis study reviewed the available evidence relating to the economic burden of RSV and PIV3 in countries with similar economic development levels. Among the viruses investigated, no eligible study about the economic impact of PIV3 was recovered. For RSV, cost analysis and COI studies were performed for populations in Colombia, China, Malaysia, and Mexico.

In a recent publication, Zhang et al.5 reported an estimated global cost of RSV-related ARI, from a healthcare payer's perspective, in €4.82 billion (costing year 2017). This value accounted for 0.7% of the global healthcare expenditure in 2017. As expected, it was reported a substantial difference in costs between settings, with inpatient costs in UCMI accounting for €1.53 billion per year, and in HIC accounting for €1.15 billion per year.5

In the investigation with UCMI, comparing the total economic impact, the lowest cost per patient at the pediatric ward was observed in Malaysia ($ 347.60), while the highest in Colombia ($ 709.66). On the other hand, at pediatric ICU, the lowest cost was observed in China ($ 1,068.26), while the highest was in Mexico ($ 3,815.56). These results indicate that even among countries with similar economic development levels, a substantial difference in costs is presented.

The authors partially explain this difference due to the overall economic situation, healthcare resource utilization, and different characteristics of each population. As observed in Table 3, although many studies assessed similar outcomes, they reported varying measurement units for the cost analysis. Therefore, any generalizability of the results to a regional or global level should be taken with caution.

There was a trend for higher hospitalization rates in patients with baseline risk status. Overall, in cost analyses, characteristics such as prematurity, underlying illness, and ICU admission, are known to increase the economic burden.5,20 Understanding the factors that may affect cost estimates and the magnitude of the economic impact is a fundamental background for economic evaluations.21

Chan and Abdel-Latif17 performed a cost analysis for children with risk factors. The authors observed that ex-prematurity and the presence of an underlying illness (e.g., congenital heart disease and cerebral palsy) are correlated to a longer period of hospitalization with a significant escalation in the costs for all aspects of resource utilization of their hospital treatment (p < 0.001). It is estimated an increase of over 10 times in the total cost.

In the same manner, Zhang et al.19 identified chronic lung disease and respiratory distress as independent risk factors of greater hospitalization costs. Moreover, a multivariable logistic regression, with control of other variables, revealed that, in their model, children aged over six months old had more hospitalization costs when compared with younger children (≤6 months). When compared to this age group, it is estimated an increase of 1.13 and 1.20 times in the total hospitalization cost for children seven to 24 months of age and over 25 months (p < 0.001), respectively.

Buendía et al.15 constructed a decision tree model to estimate the cost of each episode of RSV infection with a time horizon of two years. The authors estimated a cost approximately two to five times higher among patients hospitalized with long-term complications, than those hospitalized without long-term complications and not hospitalized. In the probabilistic sensitivity analysis, the differences were sensitive to changes in the cost of recurrent wheezing, outpatient visits, and hospitalizations.

Another important point for discussion in the present study's findings is the cost drivers. Although there is no consensus on the major cost driver, all included studies described that the medications (treatment) consumed over 30% of the total cost. Overall, the medications with the highest average costs were nebulization with a hypertonic solution, systemic antibiotics, and parenteral fluids.14,16

Buendía and Patiño14 classified all prescription drugs in their study as appropriate or inappropriate, as recommended by the Colombian guidelines for bronchiolitis. The authors reported that 96.1% of β-lactam antibiotics, over 90% of bronchodilators (albuterol, ipratropium bromide, and terbutaline), and over 85% of corticosteroids (systemic and inhaled) were classified as inappropriate.

In the literature, it is well reported the inappropriate use of medications among RSV-infected patients. This problem may be aggravated by the absence of strong evidence from some medications, such as antibiotics, demonstrating effectiveness in the treatment of diseases or complications of viral etiology.22-24 According to a guideline from the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics, a systematic review of clinical trials demonstrated that the routine use of antibiotics does not reduce symptom days, length of hospitalization stay, O2 requirement, and hospital admission rate.25

Samson et al.26 reported that children hospitalized with RSV infection and treated with antibiotics present a significant increase in the number of adverse events, mainly related to intravenous complications. Quintos-Alagheband et al.23 reinforced the great concern with inappropriate use of antibiotics, that may lead to the selection of resistant organisms.

It is well known that infections associated with multidrug-resistant organisms are responsible to increase morbimortality, length of stay, and healthcare costs.23 In this context, existing evidence-based guidelines, from different international pediatrics societies, discourage routine use of antibiotics for the treatment of bronchiolitis in babies or children with viral infections, unless there is a specific diagnosis of coexistent bacterial infection.22,24

This systematic review has some limitations that should be noted. First, of the studies included in the review, only Buendía et al.15 estimated indirect costs. The authors reported that about 15% of the cost generated by the RSV infection was attributable to this measure.15 In previously systematic reviews of other respiratory virus diseases, indirect costs were pointed as the primary driver of total costs, accounting for up to 70% of the burden.27 Therefore, the perspectives presented may be underestimated.

Second, the authors did not include in the selection process a full cost analysis, such as cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness. The authors have chosen to adopt this exclusion criterion based on previous systematic reviews of the economic burden that reported that although this study design may present primary cost evaluation, the amount of evidence that effectively is not based on secondary sources may not impact the review results.6

ConclusionIn conclusion, the systematic review highlighted how RSV infection represents a substantial economic burden to health care systems and to society. The findings of the included studies suggest a possible association between baseline risk status and expenditures. Moreover, it was observed that an important amount of the cost is destinated to treatments that have no evidence or support in most clinical practice guidelines. Therefore, conscient dispensing services may be a potentially significant cost saving. Unfortunately, due to the lack of publications, the authors could not access the economic impact of PIV3 infections. Further research in the area is needed.

FundingCRRF had financial support from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 – number 88887.505900/2020-00 (URL: https://www.gov.br/capes/pt-br). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institution or service with which the work is associated for indexing in Index Medicus/MEDLINE, City, Country: Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil.