To provide a narrative review of the main eating disorders (ED), specifically focusing on children and adolescents. This review also aims to help the pediatrician identify, diagnose, and refer children and adolescents affected by this medical condition and inform them about the multidisciplinary treatment applied to these disorders.

Data sourceThe research was conducted in the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline) databases via PubMed and Embase. Consolidated Guidelines and Guidebooks in the area were also included in the review to support the discussion of ED treatment in childhood and adolescence.

Data synthesisED are psychiatric condition that usually begins in adolescence or young adulthood but can occur at any time of life, including in childhood, which has been increasingly frequent. Pediatricians are the first professionals to deal with the problem and, therefore, must be well trained in identifying and managing these disorders, which can be severe, and determine physical complications and quality of life of patients and their families.

ConclusionED has shown an increase in prevalence, as well as a reduction in the age of diagnosed patients, requiring adequate detection and referral by pediatricians. The treatment requires a specialized multidisciplinary team and is generally long-lasting for adequate recovery of affected individuals.

Eating disorders (ED) are psychiatric conditions that usually start in adolescence or young adulthood, but can occur at any time in life, including during childhood, which has become increasingly common, especially after the recent Covid-19 pandemic.1

Pediatricians are the first professionals to deal with the problem and therefore need to be well trained in identifying and managing these disorders, which can be serious and cause physical and psychological complications and compromise the quality of life of the patient and their families.2

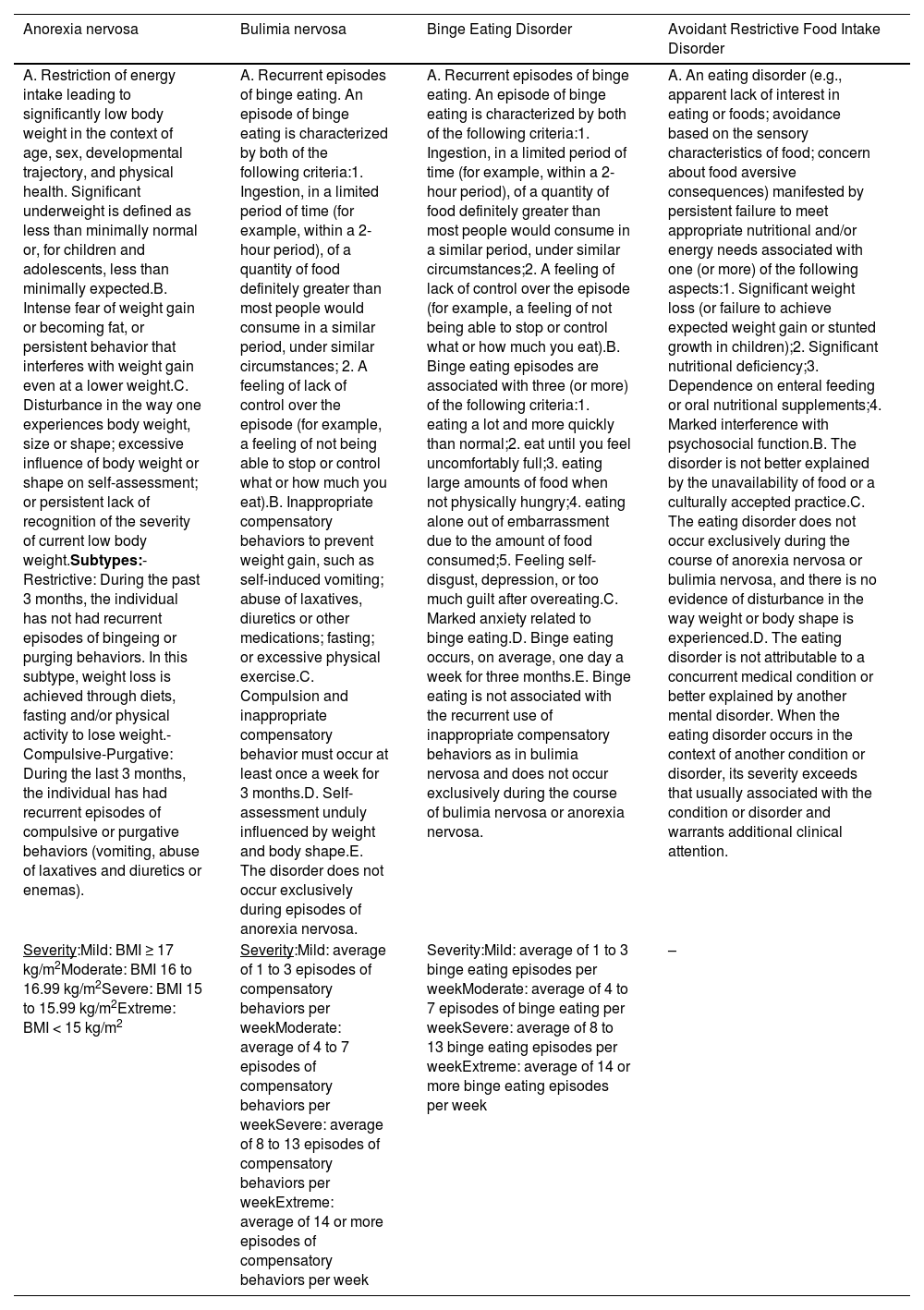

The following are included as eating disorders in the DSM-5:3 Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), Pica and Rumination Disorder. Table 1 shows the diagnostic criteria for ED, according to DSM-5.

Diagnostic criteria for Eating Disorders as shown in DSM-5.

AN is characterized by restricted caloric intake, resulting in an inappropriate weight for age, sex, growth trajectory, and physical health. In these cases, associated with malnutrition, there is an intense fear of gaining weight and changes in the way the patient evaluates their body and current weight:3

It is classified into two subtypes:

• restrictive subtype: when, in the last three months, there has been food restriction without, however, the presence of compensatory purging behavior (example: induction of vomiting, abuse of laxatives/diuretics, intense physical activity);

• purgative subtype: when, in addition to food restriction, purgative behaviors occur.

A patient can start the condition as a restrictive subtype and then migrate to the purgative subtype and vice versa.4

BN is characterized by episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory purging behaviors, with the aim of losing weight. Patients experience changes in body image and tend to be of normal weight or even overweight, which makes the disorder difficult to detect. The most accepted definition of what constitutes an episode of binge eating is consuming an excessive amount of calories in a short period, generally two hours, with the feeling of “loss of control”. This is accompanied by compensatory purgative behaviors that may include, in addition to self-induced vomiting, intense physical activity and abuse of the aforementioned laxatives and diuretics, insulin retention (called diabulimia or eating disorder-type 1 diabetes mellitus) and fasting.5

The inclusion of the Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the DSM-5 in 2013, allowed the diagnosis of children who restrict their intake due to mainly neurosensory causes, which may require medical monitoring due to extremely low weight or specific nutritional deficiencies, which often compromise their social life. These children, because they consume few, very specific food items, miss moments of social interaction mediated by the act of eating (birthday parties, meetings at friends’ houses). The patients are aware of being underweight and, in many cases, there is a desire to gain body weight, but for them eating is uninteresting and even aversive.3

Three subgroups with distinct characteristics are reported:

- •

Group I: food refusal due to poor appetite or lack of interest in food;

- •

Group II: food refusal due to the sensory properties of the food (smell, color, texture);

- •

Group III: food refusal for fear of the negative consequences of eating (fear of feeling sick, choking, or vomiting).

ARFID is more common in boys and can be preceded by pathologies related to the gastrointestinal tract, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease which, due to pain, nausea, or vomiting, can trigger food aversion.3

Binge eating disorder (BED) is more common in girls and the mean age at diagnosis is 23 years old, but it is believed that its onset occurs in childhood. This disorder is characterized by the occurrence of episodes of binge eating, but which progresses without body image distortion or adopting compensatory purgative methods for weight loss.6 Pediatricians need to be aware that around 50 % of affected patients have normal weight and the other half are overweight or obese and have comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.6 BED also shows psychiatric comorbidities, such as social phobia, depression, alcohol and drug abuse, and Atention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. It is important to highlight that BED, despite being less common in boys when compared to girls, is the most common ED in the male sex.6

EpidemiologyPopulation studies show that the incidence rate of AN seems to be stable while early-onset AN (before age 14) is increasing in number of cases and severity. ARFID has also increased since the introduction of the DSM-5 criteria in 2013. During their lifetime, around 4 % of women and 0.3 % of men have AN while, in the case of BN, the percentage is 3 % for women and 1 % for men 7. It is likely that the most prevalent ED is BED, with estimates of 2 to 4 %. The prevalence of ARFID is unknown but it is estimated at around 3 %.2

EtiologyED has a multifactorial etiology in which genetic, psychological, biological, socio-family, and cultural aspects interact. There are some personality traits associated with anorexia, such as perfectionism, low frustration threshold, low self-esteem, and impulsiveness.6,8,9 Also in the case of AN, studies on monozygotic twins show a concordance of around 50 to 60 %.

It is common for patients with BN to also have low self-esteem, impulsiveness, and difficulty in interpersonal relationships. There is a higher prevalence of affective disorders (75 %), depression (63 %), and anxiety (63 %) in this ED. The comorbidity with personality disorders makes treatment more difficult and can worsen the prognosis, as well as showing an increased risk of suicide, self-harm, kleptomania, drug and alcohol abuse, and promiscuous sexual behavior.9

It is a fact that environmental influences play a role in the development of ED, but there must be a combination of factors, especially individual vulnerability.9

ED in the male sexIt is common for males to be underrepresented in studies on ED. The new DSM-5 criteria allowed more eating disorders in boys to be identified by a specific diagnosis rather than a residual category such as “unspecified eating disorder.” The inclusion of ARFID in the DSM-5 allowed verifying that, typically, individuals affected by this disorder are more often male and symptoms begin in childhood.3

Boys may be less likely to seek treatment compared to girls, likely due to a double stigma: the stigma of suffering from a psychiatric disorder and an additional stigma: shame and discrimination regarding sexuality. Boys with ED, especially with BED, generally report less concern about shape and weight, desire for thinness, and body dissatisfaction than girls. While girls want to be thin, boys want to be “bigger” and more muscular. One exception to this is boys with anorexia nervosa, who may be more likely to worry about being thin rather than muscular.8

Homosexuality has been identified as a male-specific risk factor for developing ED and people who identify as transgender, non-binary, or gender diverse have a two to four times increased risk of eating disorder symptoms or abnormal eating behaviors than their cisgender peers.8

Initial assessmentEarly identification and detection of ED are vital to achieving good long-term results. An initial assessment should contain a focused history and physical examination with an emphasis on symptoms such as food restriction, binge eating, purging, and excessive exercise. It is necessary to seek information about daily food intake and weight history, as well as a mental health assessment involving stressors, self-critical thoughts, mood, suicidal tendencies, self-harm, sleep, substance use, energy level, and concentration. The menstrual history should also be obtained.6,10

Common physical symptoms of ED should also be assessed, including gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, nausea, presyncope, palpitations, chest pain, weakness, fatigue, lanugo, dry skin, hair loss, muscle cramps, joint pain, paleness, easy bruising and intolerance to cold. Signs of purging may include abrasions on the joints of the hands, poor dentition, halitosis, and hypertrophy of the salivary glands.10,11 Pediatricians should keep in mind, to consider a diagnosis of ED, that these conditions have peculiar symptoms in children and prepubertal children.

Partial syndromes, which do not meet all the criteria for ED, are prevalent and cause losses as serious as the total conditions and deserve treatment. The symptoms change over the years, with the patient's age and cognitive evolution and the objectives are early identification and intervention to prevent serious and chronic illness.10

In children, growth curve stagnation with the inability to reach the weight and height expected for the age group deserves particular attention. Moreover, when assessing weight, the BMI percentile should be used and not the fixed BMI, as in the case of adults. Pediatricians should emphasize the need for weight restoration, including a discussion of the medical and psychological effects of insufficient nutrition and health consequences.10

Families and patients must be informed of the multifactorial etiology of these disorders, aiming at reducing conflicts involving blame and accusations. When available, patients should be referred to a service specialized in the treatment of ED and families should always receive psychoeducational guidance.10

The pediatrician should request the following initial tests: complete blood count, renal function assessment, measurement of electrolytes, extended electrolytes, liver enzymes, albumin, vitamin B12, ferritin and lipid levels. Further investigations may also be considered to rule out other causes of symptoms, including measuring levels of thyroid hormones, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, estradiol, androgen, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Urinalysis can help assess hydration status, presence of ketones, and proteinuria. Electrocardiography should be performed to rule out bradycardia, arrhythmias, and prolongation of the corrected QT interval.10,11

The following are indicators of severity and need for hospitalization:10

- •

< 75 % of the treatment target weight;

- •

core temperature <35.6 °C (<96.0°F);

- •

heart rate <50 BPM during the day or <45 BPM at night;

- •

blood pressure <90/60 mm Hg or orthostatic hypotension (sustained increase in pulse >40 BPM or a sustained decrease in blood pressure >10 diastolic or >20 systolic mmHg/min from the lying to the standing position);

- •

ECG showing arrhythmia, prolonged QTc interval, or severe bradycardia;

- •

electrolyte abnormalities (e.g.: hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia);

- •

uncontrolled bingeing or purging;

- •

dehydration;

- •

acute comorbid psychiatric disorders or other pathology that results in an impediment to care for the eating disorder (for example: type 1 diabetes mellitus);

- •

active suicidal ideation.

Some complications resolve with effective nutritional rehabilitation and weight gain, while others can lead to permanent damage. There are alterations in almost all organs. If the patient has the purgative form, water and electrolyte disturbances are more common than in the restrictive form. Hypoglycemia is also common.11

Myocardial atrophy with mitral valve prolapse is common in extremely malnourished patients. Sinus bradycardia, profound reversible sinus node dysfunction, and orthostatic hypotension are consistently observed in patients with severe AN. As the patient's weight parameters decrease, bradycardia and hypotension become more pronounced and QT prolongation may occur.12

Most female patients who have already experienced menarche become amenorrheic and have low estrogen levels, returning to the prepubertal status, while male patients have low testosterone levels. There is marked bone mineral density loss, which can lead to early osteopenia and osteoporosis, even in adolescent patients, and this loss can be permanent. Pulmonary complications include conditions such as spontaneous pneumothorax and aspiration pneumonia. Patients may also experience generalized brain atrophy, damaged gray and white matter, and cognitive deficits that persist after treatment.10,12

Gastroparesis and constipation are common. Aminotransferase levels are often elevated in AN. There are two main causes. In the beginning, before refeeding begins, it is likely to be caused by apoptosis – programmed cell death of hepatocytes triggered by starvation. However, if levels begin to rise abnormally with refeeding, it is more likely to be caused by steatohepatitis, which responds to a change in the macrocomposition of the diet with a reduction in carbohydrate calories. Surprisingly, albumin levels are normal even with severe AN. The gelatinous marrow transformation occurs as malnutrition worsens. Specifically, serous fat atrophies in the bone marrow, and normal marrow fat is replaced by a thick mucopolysaccharide substance that prevents precursor cells from leaving the bone marrow. This leads to trilinear hypoplasia with leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia detected in this order of decreasing frequency.12

AN is characterized by marked cerebral atrophy in brain imaging studies. Specific areas of the brain seem to be preferentially damaged, including gray and white matter and areas of the insula and thalamus. With weight restoration, these brain size abnormalities seem to be reversed, but there may be ongoing cognitive deficits that persist as a secondary medical complication of AN, with permanent adverse sequelae. Brain atrophy may explain the abnormalities in taste, smell, thalamic function, and temperature regulation, as well as the overall mental slowness observed in people with more severe forms of the disease.12

Medical complications of BNThere is a risk of electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis.12 Russell's sign arises from self-induced vomiting and refers to the development of calluses on the dorsal surface of the dominant hand due to traumatic irritation of the hand by the teeth, resulting from the repeated insertion of the hand into the mouth to induce vomiting. Dental erosions and trauma to the oral mucosa and pharynx occur. Parotid gland hypertrophy, or sialadenosis, may develop in more than 50 % of patients who purge through self-induced vomiting.5

Cardiac complications include electrolyte disturbances as a result of vomiting and abuse of diuretics or laxatives. Conduction disturbances, including severe arrhythmias and QT interval prolongation, may occur due to the resulting electrolyte disturbances, especially hypokalemia and acid-base disturbances. Furthermore, excessive ingestion of ipecac, which contains the cardiotoxic alkaloid emetine, to induce vomiting can lead to several conduction disturbances and potentially irreversible cardiomyopathy.6,5 Diet pill abuse is associated with arrhythmias.

Excessive vomiting exposes the esophagus to gastric acid and damages the lower esophageal sphincter, increasing the propensity for gastroesophageal reflux disease and other esophageal complications, including Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Rupture of the esophagus is rare but can occur.5

Induction of vomiting increases intrathoracic and intra-alveolar pressures, which can lead to pneumothorax. Individuals involved in excessive and chronic abuse of stimulant laxatives may be at risk for a “cathartic colon,” a condition whereby the colon becomes an inert tube unable to move feces forward. This is believed to be due to direct damage to the myenteric nerve plexus of the intestine. Melanosis coli, a black coloration of the colon with no known clinical significance, is frequently reported during colonoscopy in people who abuse stimulant laxatives.5

An endocrine complication of BN is irregular menstruation, as opposed to the amenorrhea often seen in the restrictive and purgative subtypes of anorexia nervosa.5

Mortality and follow-upThe crude fatality rate for AN is about 5 % per decade. Death most commonly results from clinical complications associated with the disorder itself or suicide.3 About 20 % of deaths in patients with AN are the result of suicide. Sudden cardiac death is often the cause of premature death in patients with AN.12

The DSM-53 includes an index that considers body mass (BMI) and allows health professionals to assess the severity of malnutrition and the appropriate level of care needed (Table 1).

Lethality in patients with AN who require hospitalization is approximately five times higher when compared to individuals matched for age and sex. In people following post-treatment for BN or AN in an outpatient service, mortality is approximately twice as high as in the general population. The standardized case fatality rates reported in people with BN are lower than in those with anorexia nervosa but they are still significantly elevated at 1.5 % to 2.5 %.5

Individuals with BN experience 33 % rates of non-suicidal self-harm throughout life and are nearly eight times more likely to die by suicide than the general population. Recovery rates from AN vary considerably. Studies focusing on children and adolescents report recovery rates of 17.2 % to 50 %, and those focusing on adults report recovery rates of 13 % to 42.9 %.12

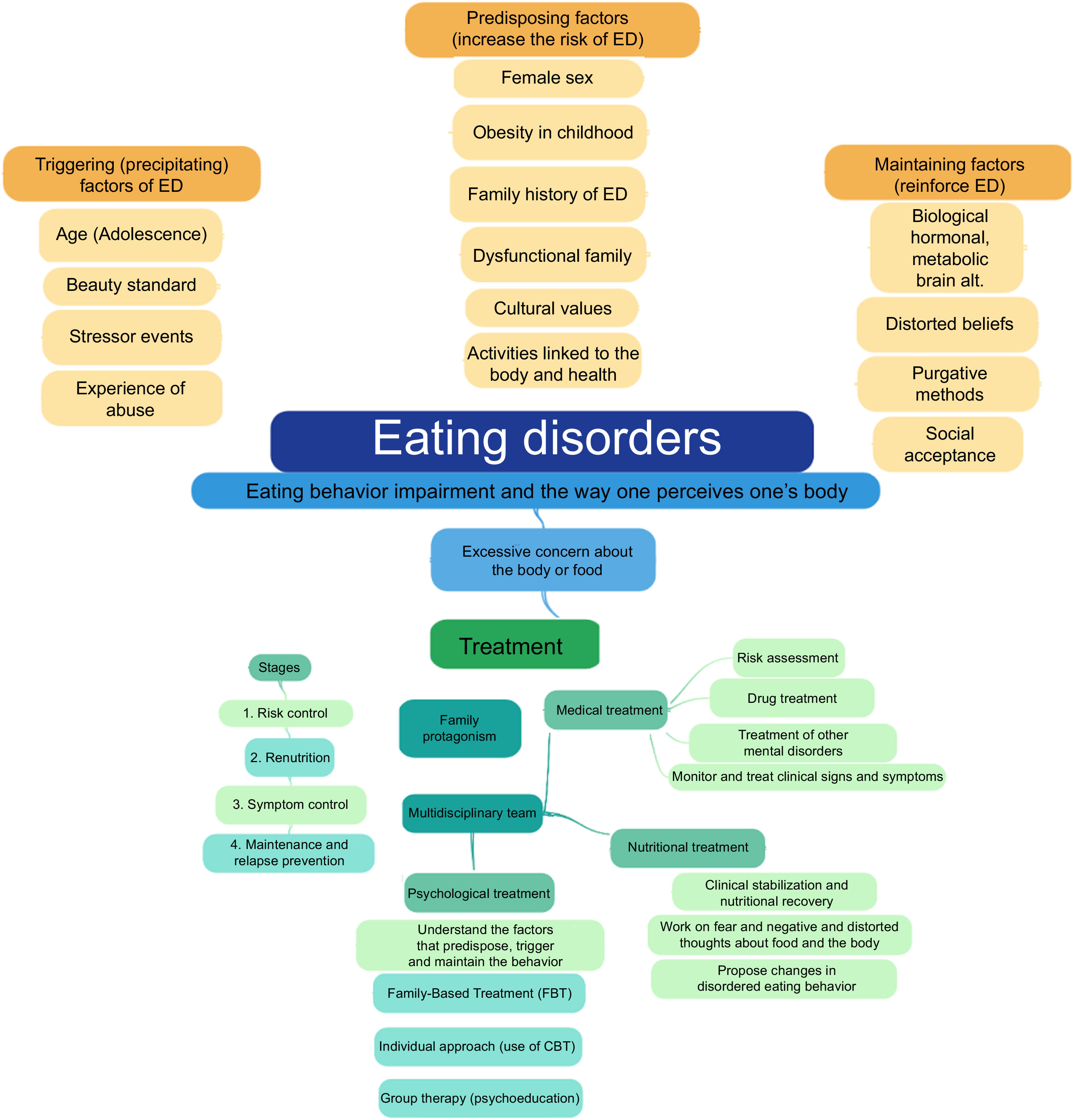

Treatment of EDClinical monitoring and research on the treatment of ED reiterate the importance and need for psychoeducation and a multidisciplinary approach to recover healthy parameters in terms of weight, growth trajectory, and relationship with food and body image (Figure 1).

Despite high relapse rates, around 9 to 52 %, especially during the first year of treatment for anorexia nervosa (AN), remission/recovery is the goal to be achieved in all cases of ED.13

Pediatric medical and psychiatric treatment is extremely important, as ED can become chronic over time and can be associated with psychiatric comorbidities, general medical and social complications, and even death due to clinical complications or suicide. The American Psychiatric Association's Practical Guide for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders (2023) suggests that some recommendations be met and that information be collected and observed when evaluating and planning the approach to patients with ED:13

- -

History of the patient's height and weight (maximum and minimum weight and recent weight changes);

- -

Patterns and changes in eating behavior (restriction, avoidance, bingeing, rumination, regurgitation);

- -

Patterns and changes in the food repertoire with the elimination of food groups from the diet;

- -

Presence of compensatory behaviors to control weight gain;

- -

Time spent thinking about food, weight, and physical fitness;

- -

Treatment and response to previous treatment of ED;

- -

Psychosocial harm resulting from concerns about diet and physical fitness;

- -

Previous and family history of eating disorders, psychiatric disorders and other general medical conditions (e.g. obesity, diabetes mellitus).

The use of medications, including psychotropic drugs, is indicated, especially when addressing comorbidities, but that is not the essential point in the treatment of ED. Nutritional monitoring and psychotherapy are required, which encompasses the family and the patient. The treatment of ED must take into account the presence of precipitating and maintaining factors, involving the patient and family dynamics, such as inadequate coping strategies, low self-esteem, and family eating practices - especially if restrictive diets are encouraged and if there is parental criticism involving food, weight, body shape.

Over the years and recently, family-based treatment (FBT) according to the Maudsley method, in addition to group educational intervention, has been recommended for families facing the stress caused by symptoms and by the behaviors displayed by a member affected by an ED. This method was developed at the Maudsley Hospital in London, in the late 1980s, to approach AN and innovated by integrating the parents into the treatment, centering the intervention on symptom management and not on the etiology of the disorder, with the following objectives.13

- -

Total parental control: the family takes control of the food and monitors the quantities;

- -

Gradual return of control to the patient;

- -

Return to the patient's normal development.

According to the 2020 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Consensus, family-based treatment:14

- -

Consists of 18 to 20 sessions over one year and includes patient care separately and jointly with family members and/or caregivers;

- -

Evaluate patient evolution four weeks after starting the approach and every three months, aiming to establish the regularity of the sessions and the total duration of the treatment;

- -

Emphasizes the supportive role of the family in the patient's recovery;

- -

Does not blame the patient or family for the development of the disorder;

- -

Includes psychoeducation about nutrition and consequences of malnutrition;

- -

Early encourages the family to temporarily assume a central role in managing the patient's diet;

- -

It occurs in three phases: the first is to establish a good therapeutic alliance with the patient and their family members, the second is to encourage the patient to develop autonomy adequate to their level of development, and the third is to plan the end of treatment.

In cases diagnosed as mild or moderate, the first stage of treatment involves an outpatient psychological approach involving the patient and family members. When symptoms worsen or there is no response to outpatient treatment, a more intensive approach is indicated, including the possibility of hospital admission.15

The following are the measures to be adopted in the case of hospital admission:16

- -

Monitor the patient's general status and carry out the necessary supplements;

- -

Prescribe an adequate diet;

- -

Refeed the patient orally, enterally, or parentally when necessary;

- -

Contain the patient's anxiety and challenging behaviors;

- -

Guide family members and staff;

- -

Monitor the patient's mental status and prescribe psychotropic drugs when indicated;

- -

Plan follow-up treatment after hospital discharge;

- -

Keep the patient safe and ensure appropriate management from a legal and ethical point of view.

The pharmacological intervention has been increasingly applied in the treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Despite weak evidence of the effectiveness of this resource in addressing the central symptoms of eating disorders, with the exception of binge eating disorder, for which there is evidence that supports the use of antidepressants and psychostimulants, psychotropic drugs are often prescribed to treat comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression. The most commonly prescribed psychotropic drugs are SSRI antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram), antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole), and lisdexamfetamine.6

According to NICE (2020),14 when prescribing medications to treat eating disorders, some fundamental aspects need to be considered:

- -

Presence of physical and mental comorbidities;

- -

The impact that malnutrition and compensatory behaviors can have on the effectiveness and safety of the chosen drug;

- -

Adherence to treatment, especially to medications that can affect body weight;

- -

Clinical complications throughout treatment, especially if medications that can alter cardiac function and electrolytes are prescribed (bradycardia, increased QT interval, hypokalemia).

Interaction with the nutrition team can be challenging for people with ED as the behavioral changes proposed throughout the nutritional treatment are contrary to the desire to “lose weight at any cost” or “not being interested in eating”, commonly observed in this group. For that purpose, it is necessary to have professionals specialized in the area to provide ethical and effective dietary care and to have the knowledge and skills recommended in treatment programs.17 Additionally, considering low individual motivation, having the participation of family and/or a support network (spouse, relatives, close friends, etc.) can favor adherence and response to treatment.18

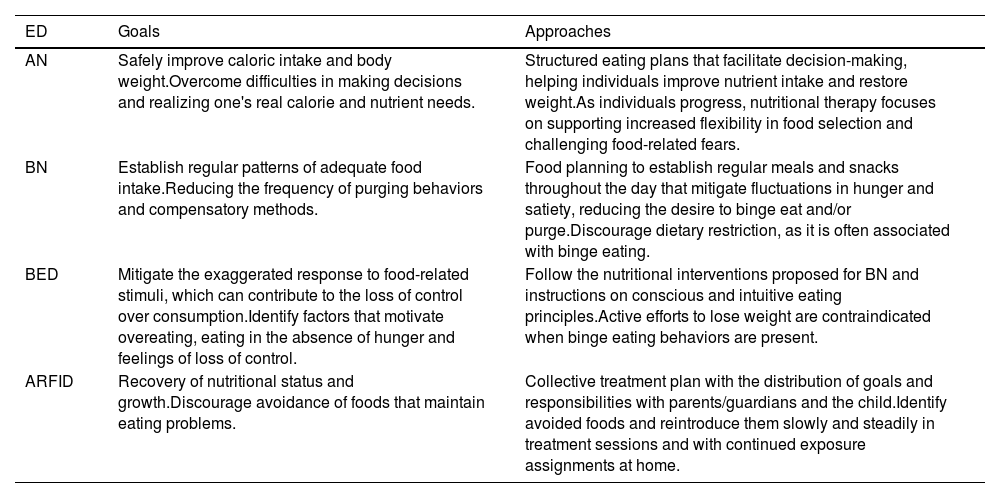

Among the objectives of nutritional treatment, the following stand out: helping individuals meet nutritional needs in a regular, balanced, and sustained manner; working on fear and negative and distorted thoughts about food, the body, and oneself; proposing changes in disordered eating behavior; contribute to weight gain (when necessary) for symptom remission; clinical stabilization and nutritional recovery. Given the objectives and considering the characteristics that comprise the ED spectrum, the nutritional approach for people with ED involves behavioral techniques.19 This approach aims to understand perceptions about eating and sensations related to eating, which can influence food consumption. For that purpose, the nutritionist must understand the connections between emotions and eating attitudes, to help the individual with the restructuring of food consumption, as well as stimulate, motivate, and engage the individual to change their behavior involving food.19

The anamnesis or nutritional screening must allow the individual to speak freely but with an investigative focus on disordered eating behaviors. It should also include the assessment of dietary history, with the history of the relationship with food, for example. The 24-hour dietary record may be limited to understanding the relationships established with food, but it can subsequently be used to quantify intake, monitor adherence to goals and identify sources of weight gain failure. When assessing food intake, descriptions of binge eating episodes, the use of compensatory methods, and the frequency with which they are practiced may be requested. An inventory of consumed, restricted, or avoided foods should be collected, as well as what motivations and/or values are attributed to the foods. Considering the relationship between food insecurity and ED, it is also important to investigate the household food supply.17,19

Regarding the assessment of the nutritional status, data from medical records (laboratory and clinical) and physical examinations focused on nutrition are used. Weight monitoring should be discussed with individuals with ED and conducted sensitively throughout consultations. All discussions about weight monitoring and assessment should be based on the principles of body positivity and similar approaches that embrace acceptance and appreciation of all body types. In the case of treatment of children and adolescents, the weights are also shared with the family and other support people.17,19

The eating plans used in the treatment of ED aim, in addition to meeting energy and nutrient needs, to provide an organized approach to food consumption and to desensitize feared excessive, or purged foods. The nutritionist can start with an individualized plan that incorporates currently consumed foods and add one or two challenging foods or increase portions. Such suggested additions to the current intake aim, over time, to get close to the adequate intake and increase the variety of foods.17,19

Often, considering the different characteristics of ED, priority therapeutic focuses are determined and goals are established for behavior modification, with defined strategies to practice, reflect on, and include the new behavior in the daily eating routine. Ideally, as individuals progress, they move away from ED-specific eating plans and behaviors toward more internally directed eating with less rigidity.19

Table 2 shows examples of approaches adopted in the nutritional treatment of ED.

Examples of nutritional goals and approaches adopted in the main Eating Disorders.

ED has a complex approach and requires specialized, long-term treatment, carried out by a multidisciplinary team. The growing prevalence of these conditions, the reduction in patients’ age, and the increase in the severity of cases call for attention and early intervention. The training of pediatricians, professionals who are on the “front line” of detecting and referring these patients, deserves all our efforts.