The Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) is a cost-free 75 question-questionnaire developed by an Italian group to collect information from parents on the behavior of children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years. It assesses different areas of children's behavior and psychopathology, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and can be used to identify children at risk of mental disorders both in clinical and epidemiological settings. In this study, the authors present a Brazilian-Portuguese adaptation of the CABI and its psychometric properties.

MethodsFirst, the authors conducted a rigorous transcultural adaptation of CABI's questions and instructions for the Brazilian context. In an online sample of 598 parents, the authors found high reliability (internal consistency) for the CABI's main subscales.

ResultsValidity was supported by exploratory factor analysis (the authors found 6 factors representing several aspects of psychopathology both according to the DSM and HiTop models) and significant differences in most CABI's subscales between children with parent-reported psychopathology and typically developing ones. The present study suggests that the adapted version of CABI is a valid and reliable measure that can be used in Brazil.

ConclusionsThe CABI can be useful to the pediatrician to get fast but wide information from parents on the behavioral condition of their children or adolescents, and also to decide whether it is appropriate to consult a mental health professional.

Half of all lifetime mental health disorders start by age 14,1 and mental disorders are one of the main causes of disability across the lifespan.2 From a policy perspective, childhood mental health is an area of significant interest as interventions targeting child development may have a high impact on human capital accumulation through child behavior.3 Consequently, the correct identification of children at risk of psychopathology is fundamental to the delivery of appropriate psychological and pharmacological treatment.4

Complexity, time, and cost are barriers to the wide use of gold-standard diagnostic measures for mental disorders in childhood.5 Therefore, brief, free, accessible, and validated measures of child mental health are quite relevant where there is limited access to expert evaluation.5 Also, even when expert diagnoses are available, the inclusion of dimensional approaches can inform the extent of a behavioral problem in each given individual.6 Screening for mental disorders in different settings, such as primary health centers, elementary and secondary schools, as well as in populational approaches may allow health practitioners an earlier diagnosis and intervention for children with behavioral problems.4

The Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) is a 75 questions-questionnaire developed by an Italian group to collect information on the behavior of children and adolescents from 6 to 18 years of age.7-9 This questionnaire was designed both for clinical and epidemiological studies. CABI was developed based on DSM-IV symptoms10 and the symptomatology was distributed according to major clusters of psychological symptoms, including social difficulties, inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, thought problems, irritability, depressive symptoms, suicidality, anxiety, trauma, somatic symptoms, eating problems, elimination problems, sleep problems, oppositional defiant behavior, conduct problems, substance abuse, bullying, and school problems. Measures of clinical evaluation and screening that cover a wide range of existing mental health problems are important in community mental health clinics (i.e., those that work with youth in routine and/or low-resource settings) where comorbidity is the norm.11 The CABI has shown similar evidence of validity and reliability to the Children Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a well-known and largely used questionnaire for the assessment of children and adolescent behavior.9 In comparison with the CBCL, the CABI, although shorter (75 items vs 113), explores a broader area of behavioral problems, has a stricter adherence to DSM criteria, allows an easier first evaluation without the use of a grid, and is free of use.

The primary aim of this study was to develop and provide initial psychometric data and preliminary normative values on a Brazilian-Portuguese translation and cultural adaptation of CABI.

Material and methodsParticipantsThis study used data from a cross-sectional study that is part of a broader research project examining the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on child and youth mental health and development. It was approved by the ethics board of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil (registry: 31,618,720.4.0000.5149). The authors assessed 598 parents using an online interface developed in SoSci Survey (www.soscisurvey.de), and consent forms were presented and accepted in the platform itself. Data were collected from July to October 2020.

The total entry was 1406 responses. From those, 659 participants were excluded for completing none of the CABI items, three for having more than 20% of missing items, and 10 for having up to 10% of missing items. Exclusions also included reports about children with less than 6 years old (N = 71) or more than 18 years old (N = 22). Responses not given by parents were also excluded (five grandparents' responses, four stepparents' responses, and 13 responses given by another caregiver). Last, 21 responses were excluded because parents did not have completed at least 8 years of education (less than middle school education).

MeasuresSamples’ characteristicsThe online survey had questions investigating participants’ sex, age in years, education, type of school, and civil/marital status when appropriate. The authors asked about the country's region of living. For economic classification, the authors used the Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria,12 a Brazilian instrument that provides evidence about the purchasing power and general situation of the households through questions about the possession of durable goods and the educational level of the head of the household. A subject score on the CCEB can vary from 0 to 100 and it is classified into one of 6 classes (A, B1, B2, C1, C2, DE) with the first letters of the alphabet indicating higher family average monthly incomes. In this study, the authors collapsed classes B1 and B2 in class B, and classes C1 and C2 in class C. Class A represents individuals with the highest socioeconomic status and DE with the lowest.

Parents were asked if their child had ever had a professional diagnosis of a mental disorder. If they reported positively, the authors requested that they check what mental disorders their child had in a list of psychiatric diagnoses based on the DSM-5 nomenclature.13 Then, the authors categorized all parent-reported diagnoses in one of five main areas: (1) neurodevelopmental, disruptive, and conduct disorders, (2) schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, (3) depressive and bipolar-related disorders, (4) anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, and trauma-related disorders, and (5) eating disorders and substance-related disorders.

Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI)CABI was designed by Cianchetti and colleagues7 as a dimensional screening questionnaire for mental disorders and problematic behaviors in children and adolescents. The questionnaire is currently free-of-cost and accessible to most health practitioners in different clinical settings. It can be used as a quantitative screening measure to estimate the intensity of psychopathology and problematic behavior in epidemiological studies, clinical research, and outpatients clinics. The CABI can also be used to investigate which symptoms are more prominent for each case.

The subscales of the current version of CABI (75 items) cover several areas of children's psychopathology and behavior: somatic symptoms, illness anxiety, sleep problems, tension, apprehension, anxiety towards school, separation anxiety, social anxiety, specific phobias, mysophobia, compulsions, obsessions, insecurity, post-traumatic stress disorder, depressive mood, lack of interest, self-esteem, abulia, guilt, suicide behavior, irritability, oppositional defiant behavior, conduct problems, impulsivity, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), reality testing, relationships, enuresis and encopresis, bulimia, anorexia, sex/gender, substance abuse, school problems, and bullying. The most representative symptoms reported in the DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria were chosen and grouped into three main subscales: Internalizing Disorders (i.e., anxiety and depressive disorders), Externalizing Disorders (i.e., oppositional-defiant and conduct disorders), and ADHD7. Both parents and teachers can answer each question on a scale with three options: 2- very true, 1- somewhat or sometimes true, or 0 - not true. Higher scores are indicative of more emotional and/or behavioral problems. In this study, the authors only have parents as a source of information on child and adolescent behavior.

Cianchetti and colleagues7 reported a high internal consistency for CABI Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms (0.822 and 0.871), as well as for ADHD items (0.873). An exploratory factor analysis of the items related to anxiety (5–10), depression (10–28), irritability (29–32), externalizing behavior (33–39), and ADHD (43–51), as well as the questions 11 and 16 (fears and insecurity), suggested a three-factor structure related to Internalizing Symptoms, Externalizing symptoms, and a mixed factor containing items of irritability and depression.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of CABI to Brazilian PortugueseTranslation and cross-cultural adaptation of CABI were performed following a rigorous guideline suggested by Souza and Rojjanasrirat:14 (1) Two knowledgeable bilingual professionals in child development and psychopathology independently translated the English version to a Brazilian Portuguese version; (2) A child psychiatry researcher and physician blindly synthesized the two independent translations combining the best cultural translation of each item; (3) The synthesized preliminary Brazilian Portuguese version was back-translated to English by two certified native English-speakers’ translators through professional contract translation services; (4) Both back-translations were discussed regarding format, wording, and grammatical structure of the sentences, similarity in meaning, and relevance compared to the original English and Italian versions. The fourth step was performed by a multidisciplinary committee with professionals from Psychiatry, Psychology, Neuropsychology, and Pediatrics, including the developer of the original CABI.

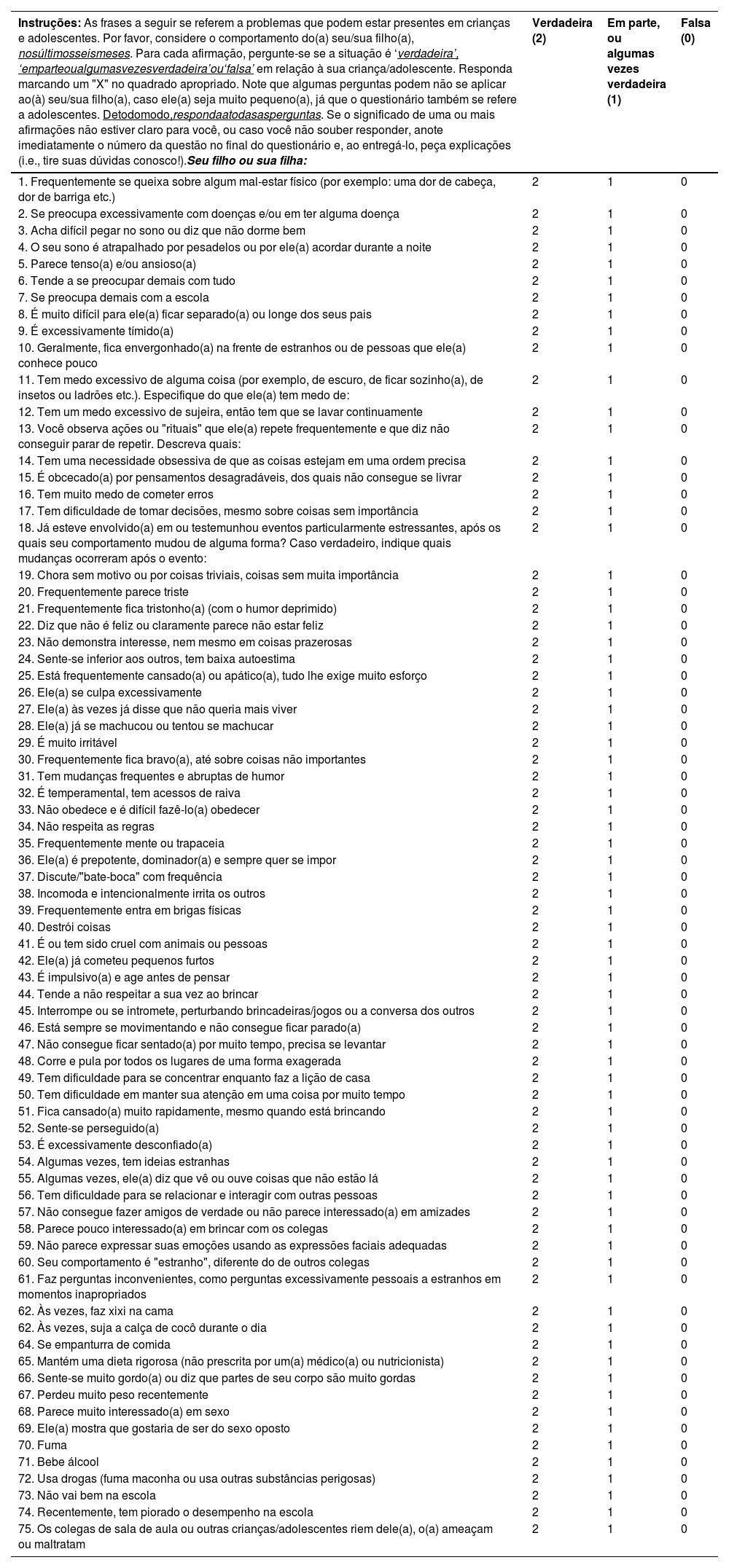

CABI instructions and response format were maintained as per the preliminary synthesized Brazilian Portuguese version, but 45 of the 75 CABI items were submitted to the previous steps until the committee reached a final consensus (changed items: 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 39, 44, 45, 48, 49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 58, 60, 62, 64, 69, 72, 75, and 90). A final Brazilian Portuguese version (Table 1) was developed and used for the following analysis. The step-by-step procedure can be requested from the authors.

Brazilian version of the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI).

Liste os números das questões cujo significado não estava claro.

Seu/sua filho(a) exibe algum comportamento que lhe parece diferente do de seus colegas? Dê detalhes.

Seu/sua filho(a) exibe algum comportamento que lhe preocupa? Dê detalhes.

Se há episódios que lhe preocupam, é melhor não os ignorar. Geralmente, problemas podem ser resolvidos se forem abordados adequadamente e em tempo. Problemas ignorados podem ser difíceis de resolver depois.

Initially, the authors conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to test the 3-factor structure proposed by Ciancetti et al. (2013) in the original paper (i.e., internalizing, externalizing, and ADHD-related problems) and tested its internal consistency using McDonald's omega and Cronbach's alpha. However, although the three factors showed adequate reliability (coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.94) the fit indexes for this model were far from ideal (RMSEA: 0.09, CFI = 0.72, TLI = 0.71), suggesting that in the present sample a different factor structure may better suit the present findings. The authors then used exploratory factor analysis using all test items (weighted least squares estimation method on the promax rotation) to analyze the CABI internal structure. Horn's parallel analysis was used to determine factor retention. The association of each CABI subscale with children's sex, age, and the socioeconomic score was investigated using Spearman correlation.

DSM classification system, though dominant in clinical practice, can be difficult to be used when interpreting quantitative analysis of mental disorders, given high comorbidity, and marked within-diagnosis heterogeneity.15 Therefore, to interpret factor analysis the authors adopted an alternative classification model based on quantitative nosology guided by statistical analyses, the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP),15 as a complementary method to understand the CABI latent structure. Briefly, HiTOP is a hierarchical model where (1) signs, symptoms, and maladaptive traits are summarized into (2) syndromes/disorders, closer to that of DSM-5 or ICD-10 disorders. At the next hierarchical level up are (3) subfactors and above them are (4) broader dimensions or spectra. So far, the model proposes six dimensions/spectrums: internalizing, externalizing-disinhibited, externalizing-antagonistic, thought disorder, somatoform symptoms, and detachment. Hierarchical levels can be up to a general psychopathology factor (p). Although the CABI was not developed using this more recent model, the authors expected that some of these dimensions would appear in the factor analysis, along with the more traditional DSM categories.

To test the preliminary clinical usage of CABI, the authors compared children with and without a history of mental disorders – as reported by their parents – on all CABI scales using the Mann-Whitney test.

All analyses were conducted in the JASP 0.14.01 software.16

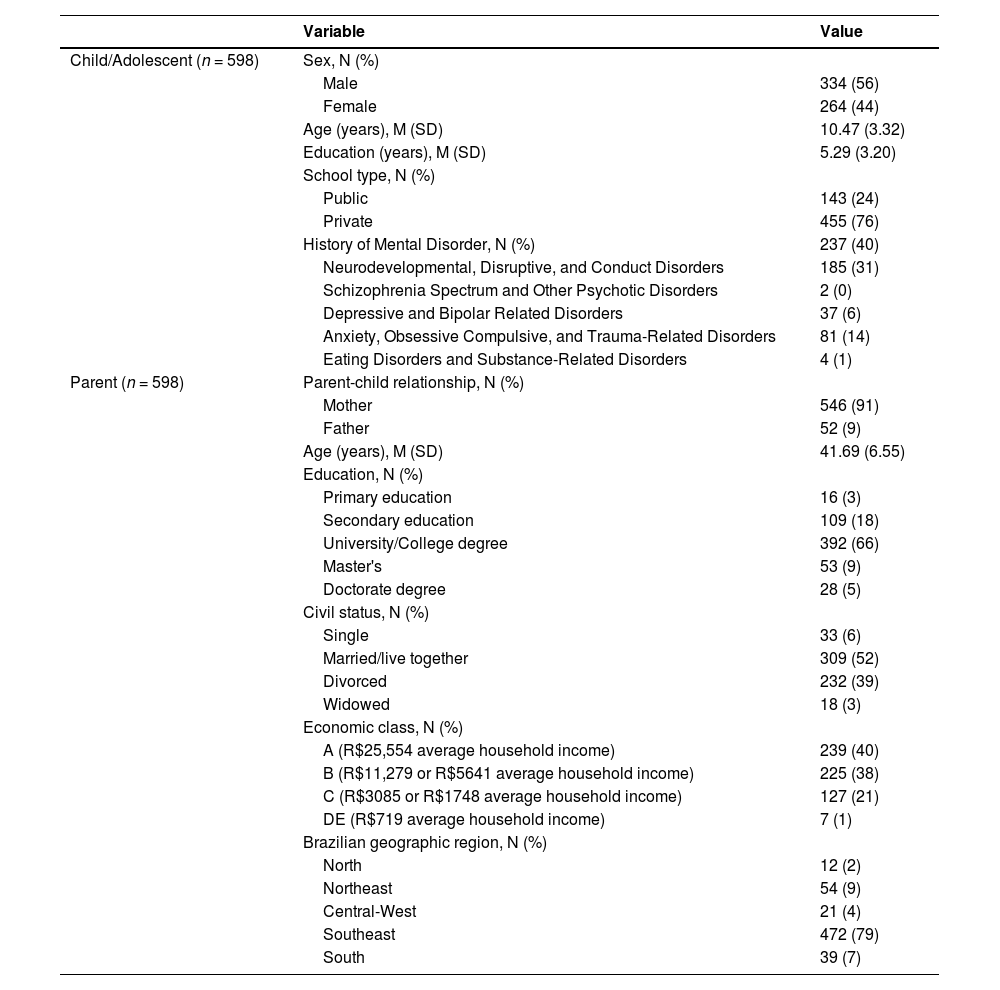

ResultsSamples’ characteristics are shown in Table 2. Most questionnaires were answered by mothers (91%). Parents’ ages varied from 24 to 66 years, most of them had a tertiary degree, were married or living together with a partner, were from Brazil's economic upper classes, and lived in the Southeast. Children's ages ranged from 6 to 18 years, sex was relatively balanced in the sample, and most of them were from private schools. According to parent reports through structured questionnaires, slightly more than a third of the sample has had a previous mental disorder diagnosis, mainly a neurodevelopmental and/or disruptive disorder.

Participants description.

M, Mean; SD, Standard Deviation.

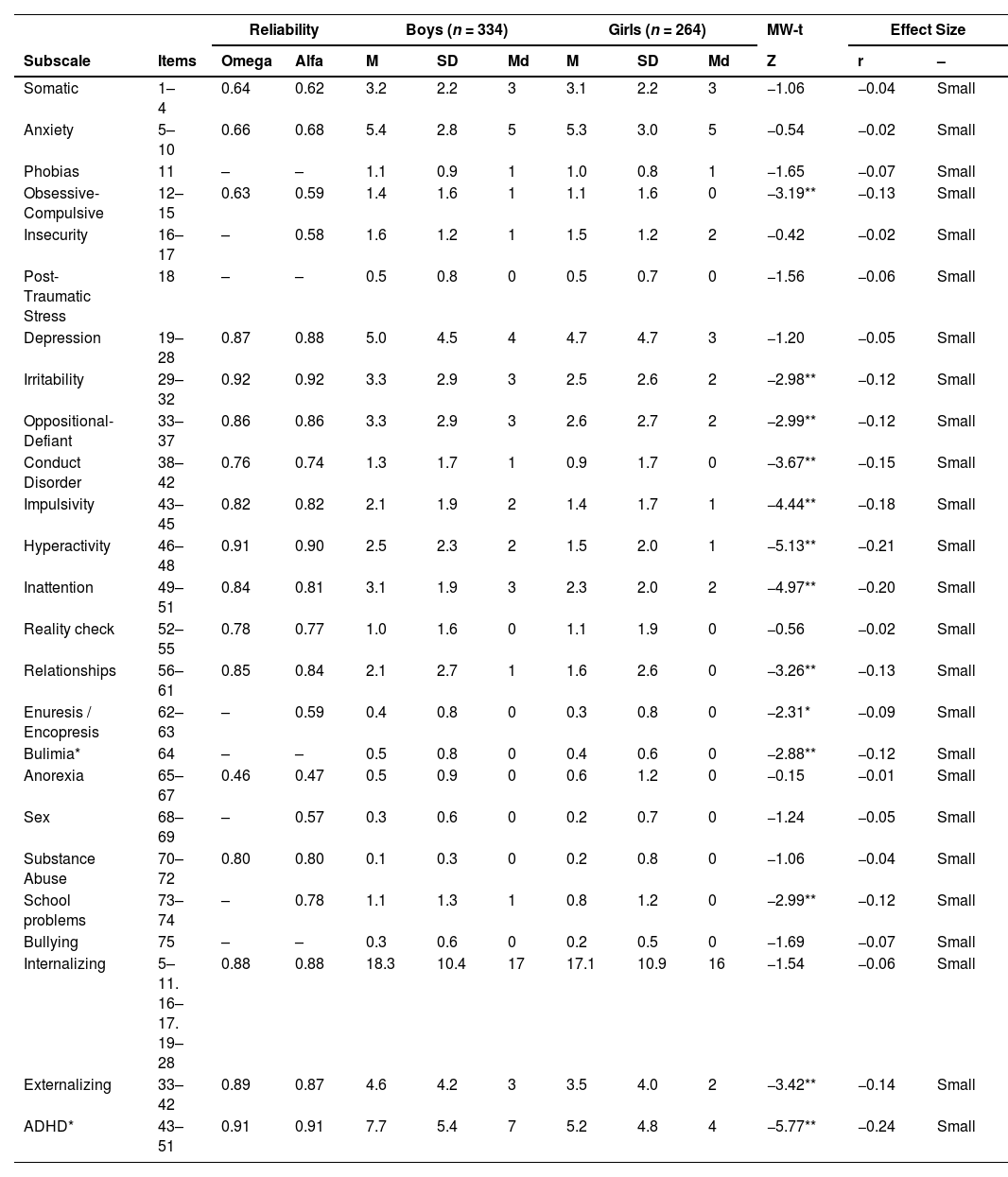

Internal consistency estimated by the McDonald's omega/Cronbach's alpha were 0.88/ 0.88 for Internalizing symptoms, 0.89 / 0.87 for Externalizing symptoms, and 0.91/ 0.91 for ADHD symptoms. Reliability for the original scales is shown in Table 3.

Comparison between Boys and Girls in the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) subscales (parent-report).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

ADHD, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; M, mean; SD, standard-deviation; Md, Median; MW-t, Mann-Whitney Test.

Regarding sociodemographic influences on CABI's scores (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 3), there were significant but small differences between boys and girls in most externalizing and ADHD subscales, in addition to the subscales of obsessive-compulsive problems, bulimia, and elimination problems. According to correlation coefficients, phobias, impulsivity, hyperactivity, and elimination problems would decrease with age, while relationship problems, anorexia, sex problems, substance abuse, and school problems would increase with age. Lower scores in the socioeconomic measure (CCEB), which indicates fewer economic advantages, were related to higher behavior problems in all but the anorexia subscale of the CABI.

In the factor analysis, the authors found a complex structure of 6 factors, some of them representing more general aspects of psychopathology (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test: 0.94, 43% of explained variance). The model showed a better fit when compared to the original one although not in the ideal ranges suggested in the current literature (RMSEA: 0.05, CFI: 0.88). Two judges classified each factor both according to the traditional DSM categories and the HiTOP model. The model facets are highlighted in italic in the following results and in Supplementary Table 2.

Factor 1 (11% of model variance) included items mainly related to inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and oppositional-defiant behavior which may represent Externalizing Symptoms – Antagonistic / Oppositional behavior – which are mainly milder signs of antisocial behavior. Items: 46, 46, 48, 45, 50, 49, 44, 43, 34, 44, 40. Omega: 0.921 / Alfa: 0.924.

Factor 2 (9% of model variance) included several symptoms of emotional distress including irritability, anger, mood changes, verbal confrontation, depressed mood, and unhappiness. This reflects the Internalizing - Distress HiTOP Dimension. Items: 38, 32, 29, 30, 31, 37, 21, 36, 22. Omega: 0.912 / Alfa: 0.910.

Factor 3 (7% of model variance) was formed by items related to fear, anxiety, obsessions, and sleep problems reflecting Internalizing Symptoms - Fear HiTOP dimension.

Items: 6, 2, 16, 7, 11, 5, 26, 4, 15, 3, 8. Omega: 0.832 / Alfa: 0.830.

Factor 4 (6% of model variance) / was formed only by items that reflected emotional instability, including irritability, anger, aggressive behavior, and mood swings, reflecting Externalizing Symptoms – Disinhibited / Irritability. Symptoms related to social functioning, including difficulties in the relationship with peers. Items: 59, 57, 09, 58, 10, 60, 59. Omega: 0.839 / Alfa: 0.841.

Factor 5 (6% of model variance), seems highly related to the social symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (although this category is not directly represented in the HiTOP model). Items: 72, 70,71,42,41, 67, 65, 69, 68. Omega: 0.755 / Alfa: 0.782.

Factor 6 (5% of model variance) seems more indicative of psychosocial outcomes and was formed by the two items of school difficulties and one question about lying. Items: 73, 74, 35. Alfa: 0.751 / Omega: 0.727

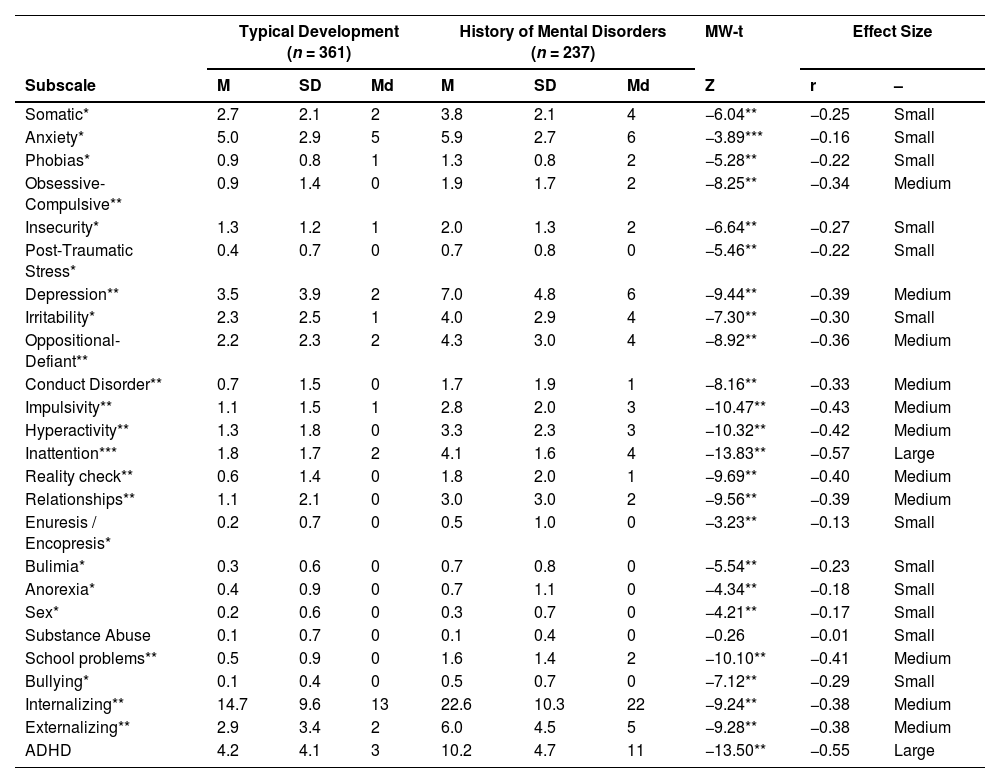

Comparing scores between children with and without a history of mental disorders (Table 4), according to parent reports, the authors found significant differences for all CABI's subscales, except for the substance abuse one. Most medium to large differences was found in subscales related to neurodevelopmental, disruptive, and conduct disorders. It is worth noting that most parents reported children's disorders in the present sample falls in the neurodevelopmental, disruptive, and conduct disorders category.

Comparison between children with and without a History of Mental Disorders according to parent report in the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) subscales.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

ADHD, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; M, mean; SD, standard-deviation; Md, Median;

MW-t, Mann-Whitney Test.

This is an authorized study to translate, culturally adapt, and validate the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) to the Brazilian context. In this sample, there was evidence of validity (content validity and factor structure) and reliability (internal consistency through Mcdonald's Omega and Cronbach's Alpha). The translation and transcultural adaptation of CABI was judiciously conducted. The processes of back-translation and content analysis by both the researchers and the original author were applied to minimize the risk of bias. As it is now, instructions, items, and the response format of the Brazilian version are the closest the research team could get from the original instrument both in English, as it was the main intention of the study, and in Italian, the country of origin of the CABI. This is essential in instruments designed to assess psychological traits and behavior since they are heavily influenced by culture and context.17 The final version can be applied in research, clinical, and epidemiological settings in Brazil.

The psychometric analysis suggests high reliability for internalizing, externalizing, and ADHD symptoms, with values ranging from 0.87 to 0.91, which are close to the original Italian version.7-9 Regarding its subscales, the values indicated subscales with very high reliability (0.92, Irritability) and others with unsuitable indicators (0.46, Anorexia). This might be due to the sample characteristics (which are not fully representative of the studied population) and the subscales composition itself (number of items, more specific or broader symptoms, symptoms more common in adolescence). Regarding its validity, although a three factor-solution was not suited for the data exploratory analysis suggested a division of six components that represented several dimensions of the HiTOP model. In this regard, it is notable that the original CABI was not based on this model, but on the DSM-IV-TR criteria.7 The psychopathology structure proposed in DSM-IV and HiTOP are different both at theoretical and measurement levels18 which may explain the relative incongruence of HiTOP dimensions on CABI factor structure. This is a recurrent problem in mental health studies where there is no definitive model of psychopathology, hindering the replication of preconceived latent studies.19,20 Nonetheless, several dimensions of the model were represented in the present analysis. To date, there is no measure that covers the full range of the HiTOP model,15 but instruments such as the CABI are helpful to characterize individual psychopathology along dimensions that can be classified in varying degrees of severity helping with clinical decision-making.

CABI seems to be a useful parent-report measure for evaluating and screening children's behavior. This might allow the pediatrician or mental health professional to screen for different behavioral problems across multiple settings of health and educational facilities.21 According to an Italian multicentric study, the CABI was accurate in classifying children as typically developing or with mental disorders, including, ADHD, depression, anxiety, and impulse control disorders.8,9 In the present study, the authors found significant differences in test scores on most subscales between children with and without a history of mental disorders, with different effect sizes. However, these children did not have a clinical diagnosis based on a structured interview and clinical analysis, so this result must be interpreted cautiously. Future studies should address this issue.

The study has limitations that must be addressed. The authors evaluated a convenience sample, which is not representative of the Brazilian population in terms of gender, socioeconomic level, and education, so the present results might not be generalized at this level. The lack of participants with clinical diagnoses limits the criterion-related validity analysis. There is a need for further studies to observe the validity of reports made by teachers and by children themselves in a cross-informant system, which generally outperforms single information procedures in predicting adolescent psychopathology.22

Data has shown that the empirical study of child mental health outcomes is dependent on measurement reliability,3 which is more attainable by adding scales and questionnaires to mental health assessment. Psychometric sound, free, brief, and accessible measures are foundational to high-quality mental health care for youth, improving treatment engagement and response.5 The CABI seems a promising tool for assessing child and adolescent behavior, showing preliminary evidence of validity and reliability. It can be useful to the pediatrician to get information from parents on the behavioral condition of their children, and also to decide whether it is appropriate to consult a mental health professional.

FundingCAPES, CNPq.

Institution where the research was conducted: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.