Sexual violence is a problem that affects children and adolescents regardless of social class, age, origin, religion, education level, marital status, race, or sexual orientation. This study aimed to analyze the associations between victim-offender relationships and the victim's age in cases of sexual violence involving female victims.

MethodsThis cross-sectional, retrospective observational study used data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health's Department of Public Health Surveillance in Brasília regarding the reportable crime of rape as informed by female victims in the Federal District between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018. The age of the victim was classified as <15 years or 15-19 years. The offenders were classified into eight different categories according to their relationship with the victim: father, stepfather, brother, husband, boyfriend, friend, stranger, and others. The association between the victim-offender relationship and the victim's age was assessed.

ResultsOverall, there were 4,617 reported cases of sexual violence, with 78.3% of these (n = 3614) corresponding to children under 15 and 21.7% to adolescents 15-19 years old (n = 1003). Close relatives, including brothers, and friends were the main perpetrators in cases of girls < 15 years old. Strangers and friends were the principal perpetrators in the group of girls 15-19 years old.

ConclusionsChildren under 15 are the group most affected by sexual violence. Strategies must be developed to prevent the sexual abuse of children and adolescents and to facilitate the rehabilitation of victimized children.

Sexual violence is an issue that affects women irrespective of social class, age, background, religion, education level, marital status, race, and even sexual orientation. This violation of human rights poses a greater threat to public health than is generally recognized because, for the most part, only a fraction of sexual attacks are reported.1,2 The prevalence of sexual violence is high both in high- and low-income countries3 with 6% to 59% of women reporting having experienced intimate partner sexual violence at some time.4 In the United States, a study conducted in 2011 found that 19.3% of women reported having been raped at some time in their life.5 Another study revealed that the highest prevalence of non-intimate partner aggression occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (21%) (95%CI: 4.5 - 37.5).6

The prevalence of sexual violence is higher among children and adolescents than in women over 20 years of age.3,6-8 In a group of university students with a mean age of 18.5 years interviewed in Canada, 23.5% reported having been raped.5 Furthermore, in a sample of high-school students in Mexico, 6.8% reported having suffered sexual violence before their 18th birthday.1 In Zimbabwe, around a third of women (32.5%) were found to have been sexually assaulted before turning 18.8

Although intimate partners are described as being the most common perpetrators of sexual violence against adult women,6,8,9 in cases involving children and adolescents stepfathers and other family members have been reported to be the most common perpetrators,9 with the victim being acquainted with the offender in at least two-thirds of cases.3,7 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, however, no studies have been conducted to assess associations between victim-offender relationships and the victim's age.

Since the late 1990s, any case of sexual violence in Brazil must obligatorily be reported to the Public Health Surveillance Department (Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde - SVS). The data thus collected allow the prevalence of sexual violence to be estimated according to the victim's age, and any possible association between the victim-offender relationship and the victim's age to be established. The present paper provides a detailed evaluation of the variations in the relationship between victims of sexual assault and their attackers according to the victim's age.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional, retrospective observational study conducted to analyze the data reported by public and private hospitals to the Public Health Surveillance Department in Brasilia, Brazil using the compulsory forms for rape victims collected between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018, referring to female children and adolescents up to 19 years of age.

The type of relationship between the perpetrator and victim was assessed using eight categories of victim-offender relationship: father, stepfather, brother, husband, boyfriend, friend, stranger, and others. The last category, others, includes caregivers, employers/bosses, institutional relationships, mothers, children, legal guardians, and those not identified on the notification form.

To enable the association between the victim-offender relationship and the victim's age to be analyzed, age was classified into groups of < 15 years of age or 15-19 years of age. The statistical analysis was conducted using the chi-square test, the test of homogeneity, the test of independence and Fisher's exact test.

The data used in this study are freely available in the public domain and can be found at the Internet site of the Public Health Surveillance Department where compulsory notifications are recorded. Since it is impossible to identify the victims, the need for ethical approval was waived.

ResultsThe number of female children and adolescents treated at public health clinics in Brasília after having suffered sexual violence ranged from 611 in 2012 to 703 in 2013, 522 in 2014, 467 in 2015, 723 in 2016, 770 in 2017, and 821 in 2018, making a total of 4,617 children and adolescents over the 7-year period, with an average of 659 children and adolescents per year.

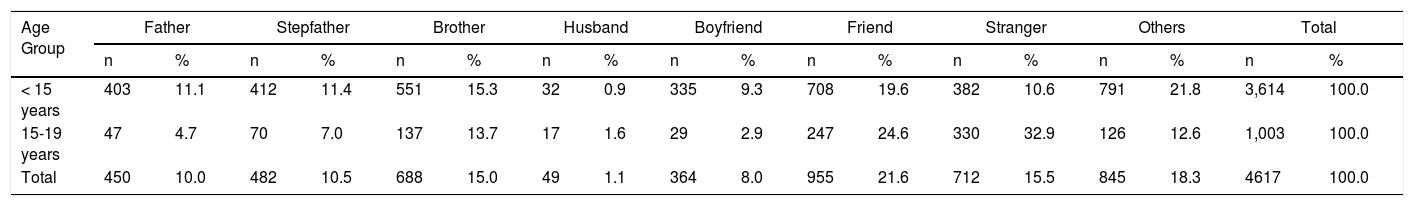

For the group of teenagers, the main perpetrators were strangers, with this category accounting for nearly 33% of all assaults, while friends were the perpetrators in around 25% of the cases (Table 1). The next most common group of perpetrators consisted of the victims’ brothers, this category accounting for around 14% of the offenders in the 15-19-year age group and for 15% of all assaults on individuals under 15 years of age, i.e. children. In this latter group, strangers were the aggressors in around 10% of cases and friends in around 20% of cases.

Percentage distribution of women reporting sexual violence according to victim-offender relationship and age group.a

Fathers and stepfathers were responsible for around 10% of all aggressions against adolescents and children irrespective of the victim's age, with the highest incidence (11.4%) occurring in the group of girls under 15 years of age.

Boyfriends represented around 9.3% of all perpetrators of sexual violence against girls under the age of 15 but less than 3% of all aggressors in cases of attacks on adolescents. Although it is rare for a husband to be the aggressor in cases of children under the age of 15, they represent around 1.6% of all perpetrators of sexual violence against adolescents of 15 to 19 years of age.

When the proportion of all assaults was assessed according to the victim's age, the group of girls under 15 years old represented around 80% of all cases (78.27%), while adolescents accounted for 21.73% (Table 1).

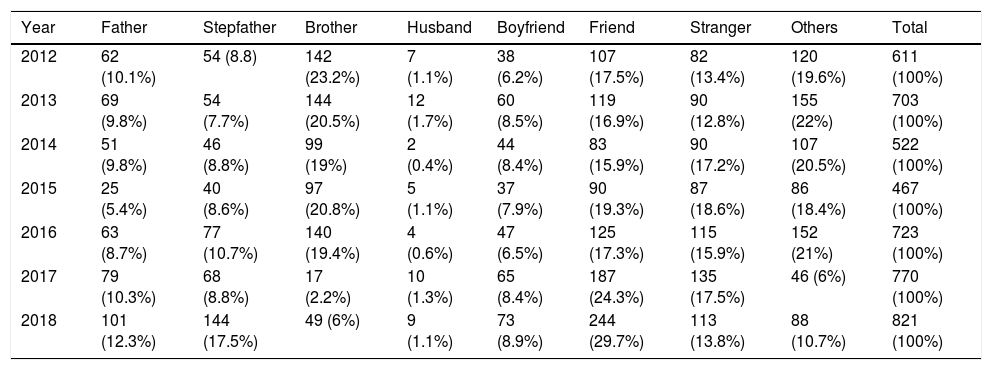

As shown in Table 2, between 2012 and 2016 brothers were the most common aggressors among family members, with fathers and stepfathers alternating between second and third place, albeit to a much lesser extent. In 2012, brothers were responsible for 142 occurrences (23.2%), and these figures remained stable over the ensuing years, with 144 occurrences in 2013 (20.5%), 99 in 2014 (19%), 97 in 2015 (20.8%), and 140 in 2016 (19.4%). It is interesting to note that in 2017 and 2018 the number of cases in which brothers were the perpetrators fell sharply to 17 (2.2%) and 49 (6%), respectively. In 2017, fathers were the most common aggressors within the family, with 79 cases (10.3%), followed by stepfathers, with 68 (8.8%). In 2018, the most common aggressors within the family were the stepfathers, with 144 cases (17.5%), followed by fathers, with 101 cases (12.3%).

Frequency of cases of rape by year and type of offender for the overall sample.

With respect to non-family aggressors, in 2012 the group with the highest number of occurrences was that referred to as others, with 120 cases (19.6%), followed by friends, with 107 (17.5%) and strangers, with 82 (13.4%). This situation continued in a similar fashion in 2013, with others then being responsible for 155 cases of aggression (22%), followed again by friends, with 119 (16.9%) and strangers, with 90 cases (12.8%). In 2014, although others remained the most common non-family aggressor, with 107 cases (20.5%), the next largest group was that classified as unknown, with 90 (17.2%) followed by friends, with 83 (15.9%). In 2015, the most common non-family aggressors were friends, with 90 cases (19.3%), followed by unknown and others, with 87 (18.6%) and 86 (18.4%) cases, respectively. In 2016, the situation returned to figures similar to those seen in 2012, at the beginning of this series, with the most common non-family perpetrators being the group classified as others, with 152 cases (21%), followed by friends, with 125 (17.3%) and strangers, with 115 cases (15.9%). In 2017 and 2018, the same unusual drop seen in the number of cases perpetrated by brothers in those years was seen for the category classified as others, where numbers dropped sharply compared to the preceding years to 46 (6%) in 2017 and to 88 (10.7%) in 2018. Over that 2-year period, the most common non-family aggressor consisted of friends, with 187 reports (24.3%) in 2017 and 244 (29.7%) in 2018. Regarding the total number of cases reported each year, values remained relatively stable at 700-800 cases per year, with the exception of 2014 and 2015 when the number of rapes was lower, with 522 and 467 cases, respectively (Table 2).

DiscussionA surprising finding obtained from the data collected for this study concerned the fact that the principal perpetrator of sexual violence against girls under 15 years of age consisted of the victim's friends, with brothers occupying second place. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is only one published paper that mentions sexual violence between siblings; however, in that paper, the victim had been murdered.10 This lack of published data highlights the rarity of this victim-offender relationship in cases of sexual violence. Other than that article, the literature review performed for the purpose of this analysis failed to reveal any other reference to a brother as a perpetrator of sexual violence against an underage sister. Some studies, however, refer to family members as being the perpetrators of sexual violence and this description may or may not include siblings.1,11

What has indeed been reported in previous studies is that friends and classmates are among the most common sex offenders against children under 18 years of age.7,12,13 In this study, there is no way of knowing whether perpetrators classified as friends in cases of sexual violence against children or adolescents were indeed classmates. However, in another study conducted in Brazil,14 the frequency of sexual assault perpetrated by friends or acquaintances was much higher (42.3%) compared to the proportion identified in the present study. The fact that the data were collected at a forensic medicine unit in that study, while in the present study the victims may or may not have attended one of these units could possibly explain this difference.

Contrary to reports in the literature, the intimate partner, represented in this study by a husband or boyfriend, does not appear to be responsible for a significant percentage of sexual assaults against women of any age group. However, there is a common belief in Brazil that a steady intimate partner such as a long-time boyfriend or husband would have the right to use their partner's body for their sexual pleasure.15 In a cultural environment in which this behavior by an intimate partner is accepted, intimate partner sexual violence will rarely be reported and, for this reason, may not be mentioned in studies such as this one, which was based on cases reported to the Public Health Surveillance Department. Therefore, it is possible that, since the present sample consists of reported cases of sexual violence, intimate partner assaults may not appear or may rarely appear in health records. In fact, some publications report that even in societies in which women feel more empowered with respect to their rights, women who have been assaulted are more likely to report assaults perpetrated by others than when the violence is committed by their own partner.3,16

In addition, the present results differ from those of other publications with respect to stepfathers and fathers as perpetrators of sexual offenses against children and adolescents. In the present study, fathers and stepfathers each constituted around 11% of all offenders, whereas in another study conducted in Brazil that percentage was much higher (27.5%).17 However, that study was based on cases treated at a forensic medicine unit.

Once again, it is evident that the fact that the present sample is made up of notified cases explains why strangers are the main aggressors of women over 15 years of age, unlike reports from other studies in which the perpetrators are in general known to the victims.1,3,7 Another study conducted in Brazil that was also based on notified cases found an even higher proportion of aggressions by strangers against girls in the 10-14-year age group (32.9% compared to the 10.6% found in the present study) and a similar proportion against those in the 15-19-year age group (33.1% compared to 32.9% in the present sample).

An important limitation of this study is that it is based on cases of sexual violence reported to the public health authorities and, as discussed above, the proportion of reported cases of sexual violence is relatively small and selective, with aggressions perpetrated by close relatives being much less likely to be reported than when a stranger commits the aggression. If more funding were available, further studies should be conducted on a representative sample of the population in order to provide a more realistic picture of the situation of sexual violence in Brazil. Irrespective of this limitation, however, the present results show that children and adolescents in the Brazilian capital are very often victims of sexual violence committed by their own brothers, fathers or stepfathers, and this has serious implications on their mental and physical health.2,6,17,18

The results of this study confirm that the age group of women most likely to suffer sexual violence consists of children and adolescents, i.e. those under 15 years of age and those of 15 to 19 years of age, particularly the former group, as already reported in the literature.3,5,10,11 Sexual violence against children is a problem that is strikingly similar in different regions around the world7,18-22 and one that appears to be more common in less socioeconomically privileged groups.17,22

These results highlight the importance of the issue of violence against children and adolescents, the consequences of which exert the greatest emotional impact of all the different forms of gender-based violence.23,24 These findings also confirm that the age group most affected by this type of gender violence consists of girls of 10 to 14 years of age, for whom the impact on their physical and psychological health is greatest, affecting them for the rest of their lives.25 In this sense, the emotional impact of sexual violence is unquestionably more serious than its physical consequences.26

Furthermore, it is important to note that a certain proportion of violence against children occurs at school27; therefore, close attention should be paid to ensure that such violence does not occur or that it is identified early to rectify its causes and avoid its consequences. Some studies have suggested that the progression of children through school constitutes a protective factor indicative of the absence of sexual violence.28 These findings should alert health and education authorities to adopt measures to prevent sexual violence, restoring the health of children and adolescents as well as that of adult women. Strategies should be developed to prevent the sexual abuse of children and adolescents and facilitate the rehabilitation of victimized children. According to a Cochrane review, the consequences of sexual violence should be determined, and the implementation of interventions should be facilitated to effectively prevent and reduce its consequences in children, not only with respect to girls but also for boys.28

Since 1997, professionals at several departments of obstetrics and gynecology throughout Brazil have set up initiatives aimed at providing care for women who have suffered sexual violence.29 In addition, the Ministry of Health has issued guidelines, most recently updated in 2012, regarding the care of women and adolescents who suffer sexual violence, including indications and procedures for the termination of pregnancy resulting from sexual violence.30 However, this post-violence care, although important and necessary, is insufficient, since it does not prevent violence. The hope of the authors is that the publication of these data will add to the information already available and encourage health authorities to develop programs specifically aimed at preventing the occurrence of sexual violence against children and adolescents.

In this study sample, female children under 15 were the group most affected by sexual violence, with the perpetrators mostly consisting of the victim's friends, while brothers occupied second place. Strategies must be developed to prevent the sexual abuse of children and adolescents and to facilitate the rehabilitation of victimized children. Further studies are required on the socioeconomic profile of these children and the distribution of cases as a function of the country's regions. Moreover, sexual violence against male children should also be investigated.