To estimate the prevalence and to analyze factors associated with breast milk donation at primary health care units in order to increase the human milk bank reserves.

MethodsCross-sectional study carried out in 2013 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A representative sample of 695 mothers of children younger than 1 year attended to at the nine primary health care units with human milk donation services were interviewed. A hierarchical approach was used to obtain adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) by Poisson regression with robust variance. The final model included the variables associated with breast milk donation (p≤0.05).

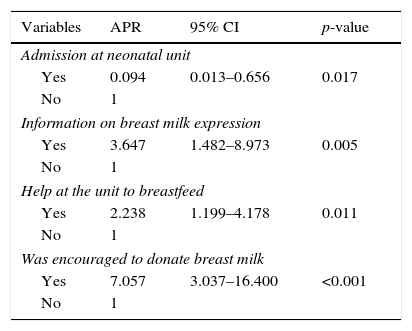

Results7.3% of the mothers had donated breast milk. Having been encouraged to donate breast milk by healthcare professionals, relatives, or friends (APR=7.06), receiving information on breast milk expression by the primary health care unit (APR=3.65), and receiving help from the unit professionals to breastfeed (APR=2.24) were associated with a higher prevalence of donation. Admission of the newborn to the neonatal unit was associated with a lower prevalence of donation (APR=0.09).

ConclusionsEncouragement to breast milk donation, and information and help provided by primary health care unit professionals to breastfeeding were shown to be important for the practice of human milk donation.

Estimar a prevalência e analisar os fatores associados à doação de leite materno em unidades básicas de saúde com vistas a aumentar os estoques dos bancos de leite humano.

MétodosEstudo transversal conduzido em 2013 na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, mediante entrevista a uma amostra representativa de 695 mães de crianças menores de 1 ano assistidas nas 9 unidades básicas de saúde com posto de recebimento de leite humano ordenhado. Razões de prevalência ajustadas (RPa) foram obtidas por modelo de regressão de Poisson com variância robusta, segundo modelo hierarquizado. O modelo final foi composto pelas variáveis que se associaram à doação de leite materno por profissionais de saúde (p ≤ 0,05).

ResultadosDoaram leite materno 7,3% das mães. Ter sido incentivada a doar leite materno por profissionais de saúde, parentes ou amigos (RPa=7,06), ter recebido orientação da unidade básica sobre ordenha das mamas (RPa=3,65) e ter recebido ajuda da unidade básica para amamentar (RPa=2,24) se associaram a uma maior prevalência de doação, enquanto a internação prévia do bebê em unidade neonatal se associou a uma menor prevalência (RPa=0,09).

ConclusõesFicou evidente a importância do incentivo à doação, das orientações e da ajuda da unidade básica para amamentar para a prática de doação de leite materno.

Breast milk is the best food for the infant; it has species-specific nutrients and a significant number of protective factors, such as IgA, IgM, IgG, macrophages, neutrophils, B and T lymphocytes, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and bifid factor.1 Breastfeeding contributes to the reduction in infant mortality, preventing infections such as respiratory and diarrheal diseases,2,3 and reducing the hospitalization rates for these infections.4,5 Breast milk composition is adapted to the newborn's gestational age.6 Feeding premature infants with human milk increases brain growth and intelligence quotients, affecting cognitive development,7,8 and reduces the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis.9 As human milk feeding is even more important for at-risk neonates, the Brazilian Ministry of Health highlights its importance for the survival of these infants.10

A human milk bank (HMB) is a specialized unit linked to a neonatal intensive care unit, and one of its missions is to stimulate the donation of breast milk to feed at-risk hospitalized newborns. They are responsible for the pasteurization and distribution of human milk, taking into account the baby's needs. However, the human milk collected by the HMB still does not meet the demand of at-risk newborns in most Brazilian states, which recently prompted the Brazilian Ministry of Health to launch a campaign to encourage the donation of breast milk, to meet the goal of a 15% increase in the volume of human milk collected in the country.11

In 2007, aiming to increase breast milk reserves, an innovative experience emerged in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Healthcare professionals from a primary health care unit (PHCU), observing mothers with excess breast milk production disposing it, created a strategy called “Breast milk expressed Receiving Services”, together with a maternity hospital that had a HMB. Breastfeeding mothers were encouraged to express the breast milk at home, which was then collected by the PHCU and sent to a nearby HMB. In 2010, this experience was incorporated by the Municipal Health Secretariat of Rio de Janeiro, which opened nine milk receiving services, which work together with reference HMBs.12

The present study aimed to estimate the prevalence and to analyze the factors associated with breast milk donation to PHCUs in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The authors believe this study may contribute to the identification of factors associated with breast milk donation, so that actions that will generate an increase in the prevalence of such donation can be implemented.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study carried out in November and December of 2013 in PHCUs of the municipality. In September and October of the same year, a pilot study was conducted in two PHCUs of the city to test the tools and define the field logistics. These two units were implementing expressed human milk receiving services and were not included in the present fieldwork. The study was carried out by six interviewers, nurses or nutritionists, and was monitored by a field supervisor and by the researchers who coordinated this investigation. These interviewers were recruited from teaching institutions where the researchers worked and received a 20-h theoretical–practical training.

The research data sources included questionnaires applied to a representative sample of the mothers of children under 1 year of age, attended to at the nine PHCUs of the city that had an expressed human milk receiving service at the time of the study.13 The mothers were asked about sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle habits, family context, care received in the prenatal period, childbirth and mother-infant care, baby feeding, as well as the practice of breast milk donation. Human milk donation encouragement was assessed by the question “Did someone encourage you to donate your milk?” The assistance provided by the PHCU to the mother-baby binomial was investigated in several ways. Help to breastfeed was assessed by the question “Do you think this health unit is helping (or helped) you to breastfeed?” To assess the help received to learn how to express milk from the breasts, the following question was asked: “Did anyone in this unit explain how to express breast milk with your hands or with the pump if you need it?”

Data collection and use followed the provisions of Resolution 466 of the National Health Council (Conselho Nacional de Saúde [CNS]).14 Data were collected after an informed consent was signed, and the mothers were informed about the study purpose and the non-mandatory nature of participation. The study was submitted to the Ethics and Research Committee of the Municipal Health and Civil Defense Secretariat and approved by opinion No. 228A/2013, of August 18, 2013.

The original study, “Evaluation of the factors associated with breast milk donation by users of PHCUs in the city”, used as basis for sample size calculation the prevalence of an assessed outcome, cross-breastfeeding, estimated at 50% based on data collected in the pilot study, resulting in a sample size of 697 mothers, considering a mean monthly demand of 1321 babies under 1 year of age attended to at the nine PHCUs that had an expressed human milk receiving service. Mothers were systematically selected at the time they took their children under 1 year of age to consultations with the healthcare team. Data were collected in all shifts of care at each PHCU until the sample size was attained.13 This sample size was adequate to detect a prevalence ratio of 1.5, with a 78% test power and alpha of 5%, having as parameter the prevalence of 7.3% of breast milk donation (outcome) found in the data analysis.

The database containing the collected information was created using Epi-Info 2000 (Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology & Laboratory Services, GA, USA), and the analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. IL, USA).

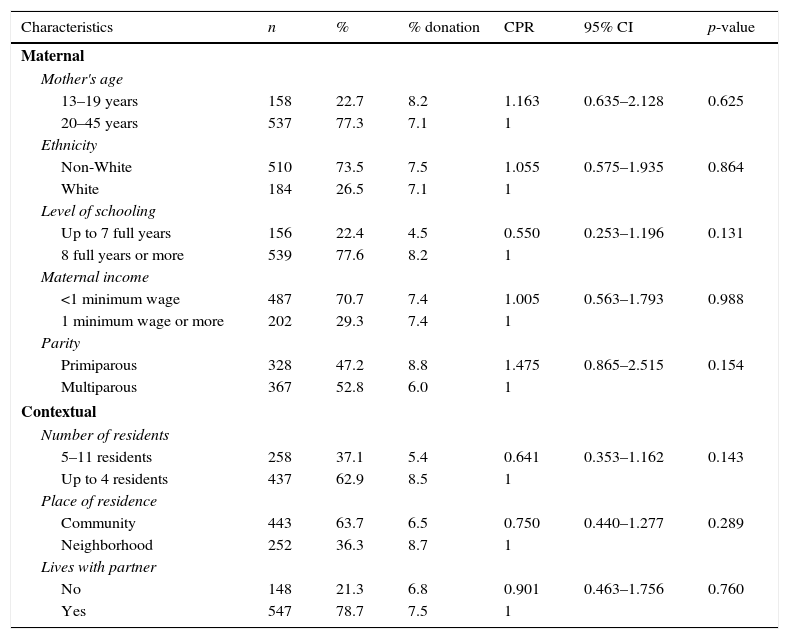

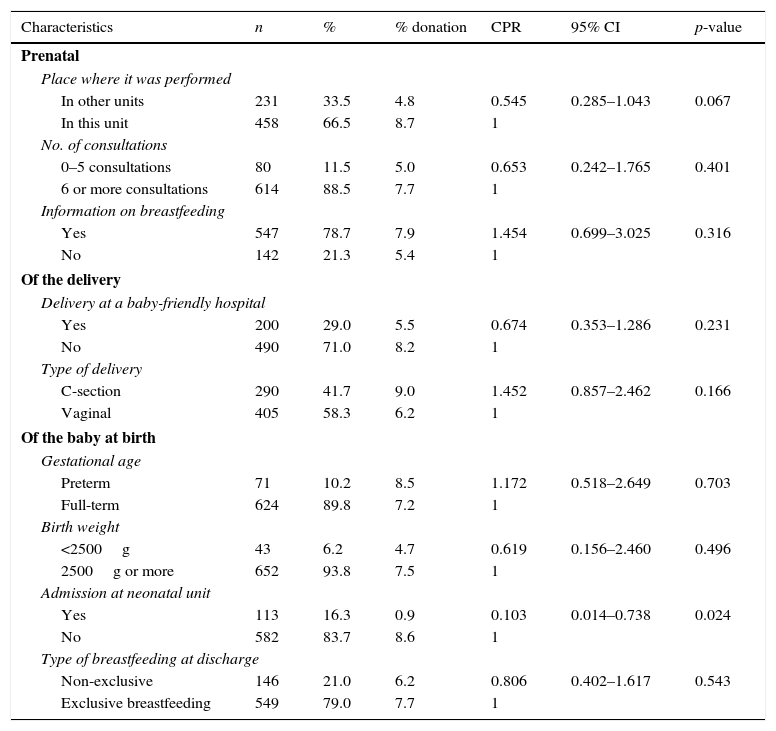

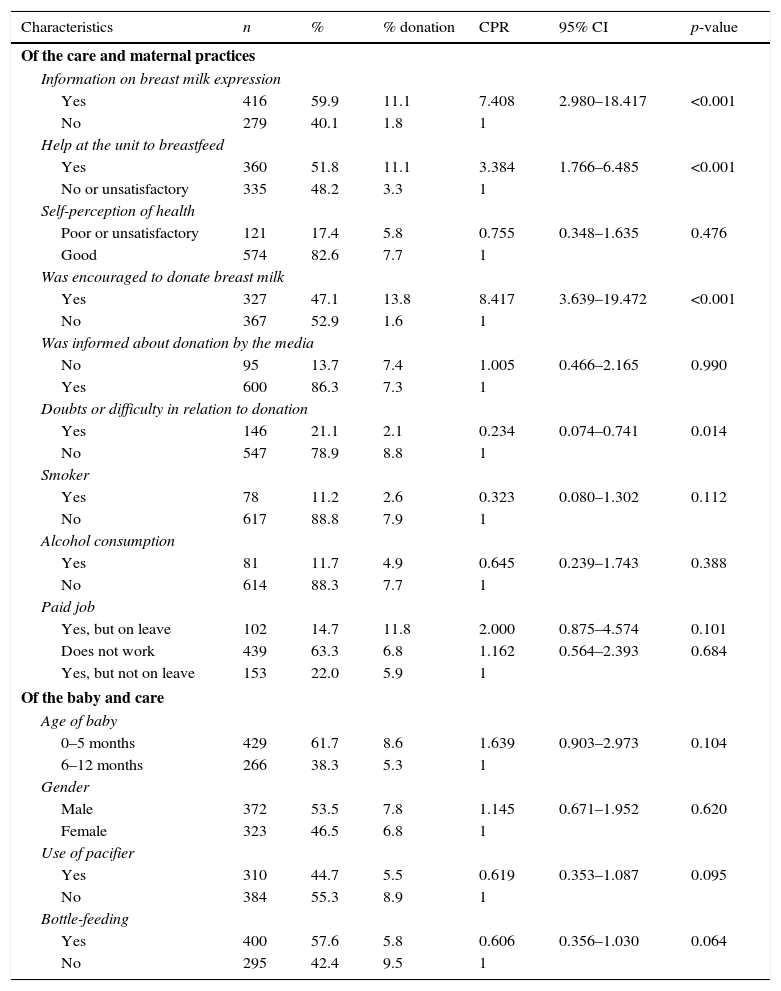

A hierarchical theoretical model of the factors associated with breast milk donation in PHCUs was created, comprising the distal variables (maternal and contextual characteristics; Table 1), intermediate variables (characteristics of the prenatal care, delivery, and of the baby at birth; Table 2), and proximal variables (care characteristics and maternal practices after the baby's birth, as well as characteristics of the baby; Table 3).

Prevalences and crude prevalence ratios of human milk donation to primary health care units according to maternal and contextual characteristics. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013.

| Characteristics | n | % | % donation | CPR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | ||||||

| Mother's age | ||||||

| 13–19 years | 158 | 22.7 | 8.2 | 1.163 | 0.635–2.128 | 0.625 |

| 20–45 years | 537 | 77.3 | 7.1 | 1 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-White | 510 | 73.5 | 7.5 | 1.055 | 0.575–1.935 | 0.864 |

| White | 184 | 26.5 | 7.1 | 1 | ||

| Level of schooling | ||||||

| Up to 7 full years | 156 | 22.4 | 4.5 | 0.550 | 0.253–1.196 | 0.131 |

| 8 full years or more | 539 | 77.6 | 8.2 | 1 | ||

| Maternal income | ||||||

| <1 minimum wage | 487 | 70.7 | 7.4 | 1.005 | 0.563–1.793 | 0.988 |

| 1 minimum wage or more | 202 | 29.3 | 7.4 | 1 | ||

| Parity | ||||||

| Primiparous | 328 | 47.2 | 8.8 | 1.475 | 0.865–2.515 | 0.154 |

| Multiparous | 367 | 52.8 | 6.0 | 1 | ||

| Contextual | ||||||

| Number of residents | ||||||

| 5–11 residents | 258 | 37.1 | 5.4 | 0.641 | 0.353–1.162 | 0.143 |

| Up to 4 residents | 437 | 62.9 | 8.5 | 1 | ||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Community | 443 | 63.7 | 6.5 | 0.750 | 0.440–1.277 | 0.289 |

| Neighborhood | 252 | 36.3 | 8.7 | 1 | ||

| Lives with partner | ||||||

| No | 148 | 21.3 | 6.8 | 0.901 | 0.463–1.756 | 0.760 |

| Yes | 547 | 78.7 | 7.5 | 1 | ||

CPR, crude prevalence ratio.

Prevalences and crude prevalence ratios of human milk donation to primary health care units according to prenatal, delivery and baby characteristics at birth. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013.

| Characteristics | n | % | % donation | CPR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal | ||||||

| Place where it was performed | ||||||

| In other units | 231 | 33.5 | 4.8 | 0.545 | 0.285–1.043 | 0.067 |

| In this unit | 458 | 66.5 | 8.7 | 1 | ||

| No. of consultations | ||||||

| 0–5 consultations | 80 | 11.5 | 5.0 | 0.653 | 0.242–1.765 | 0.401 |

| 6 or more consultations | 614 | 88.5 | 7.7 | 1 | ||

| Information on breastfeeding | ||||||

| Yes | 547 | 78.7 | 7.9 | 1.454 | 0.699–3.025 | 0.316 |

| No | 142 | 21.3 | 5.4 | 1 | ||

| Of the delivery | ||||||

| Delivery at a baby-friendly hospital | ||||||

| Yes | 200 | 29.0 | 5.5 | 0.674 | 0.353–1.286 | 0.231 |

| No | 490 | 71.0 | 8.2 | 1 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||||

| C-section | 290 | 41.7 | 9.0 | 1.452 | 0.857–2.462 | 0.166 |

| Vaginal | 405 | 58.3 | 6.2 | 1 | ||

| Of the baby at birth | ||||||

| Gestational age | ||||||

| Preterm | 71 | 10.2 | 8.5 | 1.172 | 0.518–2.649 | 0.703 |

| Full-term | 624 | 89.8 | 7.2 | 1 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| <2500g | 43 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 0.619 | 0.156–2.460 | 0.496 |

| 2500g or more | 652 | 93.8 | 7.5 | 1 | ||

| Admission at neonatal unit | ||||||

| Yes | 113 | 16.3 | 0.9 | 0.103 | 0.014–0.738 | 0.024 |

| No | 582 | 83.7 | 8.6 | 1 | ||

| Type of breastfeeding at discharge | ||||||

| Non-exclusive | 146 | 21.0 | 6.2 | 0.806 | 0.402–1.617 | 0.543 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 549 | 79.0 | 7.7 | 1 | ||

CPR, crude prevalence ratio.

Prevalences and crude prevalence ratios of human milk donation to primary health care units according to care and maternal practices after the baby's birth and baby's characteristics. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013.

| Characteristics | n | % | % donation | CPR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Of the care and maternal practices | ||||||

| Information on breast milk expression | ||||||

| Yes | 416 | 59.9 | 11.1 | 7.408 | 2.980–18.417 | <0.001 |

| No | 279 | 40.1 | 1.8 | 1 | ||

| Help at the unit to breastfeed | ||||||

| Yes | 360 | 51.8 | 11.1 | 3.384 | 1.766–6.485 | <0.001 |

| No or unsatisfactory | 335 | 48.2 | 3.3 | 1 | ||

| Self-perception of health | ||||||

| Poor or unsatisfactory | 121 | 17.4 | 5.8 | 0.755 | 0.348–1.635 | 0.476 |

| Good | 574 | 82.6 | 7.7 | 1 | ||

| Was encouraged to donate breast milk | ||||||

| Yes | 327 | 47.1 | 13.8 | 8.417 | 3.639–19.472 | <0.001 |

| No | 367 | 52.9 | 1.6 | 1 | ||

| Was informed about donation by the media | ||||||

| No | 95 | 13.7 | 7.4 | 1.005 | 0.466–2.165 | 0.990 |

| Yes | 600 | 86.3 | 7.3 | 1 | ||

| Doubts or difficulty in relation to donation | ||||||

| Yes | 146 | 21.1 | 2.1 | 0.234 | 0.074–0.741 | 0.014 |

| No | 547 | 78.9 | 8.8 | 1 | ||

| Smoker | ||||||

| Yes | 78 | 11.2 | 2.6 | 0.323 | 0.080–1.302 | 0.112 |

| No | 617 | 88.8 | 7.9 | 1 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Yes | 81 | 11.7 | 4.9 | 0.645 | 0.239–1.743 | 0.388 |

| No | 614 | 88.3 | 7.7 | 1 | ||

| Paid job | ||||||

| Yes, but on leave | 102 | 14.7 | 11.8 | 2.000 | 0.875–4.574 | 0.101 |

| Does not work | 439 | 63.3 | 6.8 | 1.162 | 0.564–2.393 | 0.684 |

| Yes, but not on leave | 153 | 22.0 | 5.9 | 1 | ||

| Of the baby and care | ||||||

| Age of baby | ||||||

| 0–5 months | 429 | 61.7 | 8.6 | 1.639 | 0.903–2.973 | 0.104 |

| 6–12 months | 266 | 38.3 | 5.3 | 1 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 372 | 53.5 | 7.8 | 1.145 | 0.671–1.952 | 0.620 |

| Female | 323 | 46.5 | 6.8 | 1 | ||

| Use of pacifier | ||||||

| Yes | 310 | 44.7 | 5.5 | 0.619 | 0.353–1.087 | 0.095 |

| No | 384 | 55.3 | 8.9 | 1 | ||

| Bottle-feeding | ||||||

| Yes | 400 | 57.6 | 5.8 | 0.606 | 0.356–1.030 | 0.064 |

| No | 295 | 42.4 | 9.5 | 1 | ||

CPR, crude prevalence ratio.

Initially, a univariate analysis model was used to assess the distribution of the exposure and outcome variables investigated; then, a bivariate analysis was carried out between each exposure variable and the outcome (breast milk donation). To obtain the prevalence ratios directly, adjustments were made using Poisson's regression model with robust variance.15

The regression followed the hierarchical conceptual model,16 and the variables were inserted in block. First, the distal variables were analyzed, followed by the intermediate variables, and, finally, by the proximal variables. At each stage of the analysis, the variables were adjusted in relation to the others at the same level and to those that showed an association with a significance level ≤20% in the chi-squared test (p-value ≤0.20) at previous levels.

The final model, used to estimate measures of association with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), consisted of the exposure variables that obtained an association with the outcome with an observed significance level ≤5% (p-value ≤0.05).

ResultsA total of 695 mothers of children under 1 year of age were interviewed in the nine units that had an expressed human milk receiving service, and 7.3% of the mothers had donated breast milk to the PHCUs.

In the bivariate analysis, the following variables were associated with human milk donation (p-value ≤0.20): the distal variables maternal schooling, parity, and number of residents in the household (Table 1); the intermediate variables prenatal care location, type of delivery, and previous hospitalization of the baby in a neonatal unit (Table 2); and the proximal variables information on breast milk expression, help at the unit to breastfeed, having been encouraged to donate breast milk, doubt or difficulty regarding milk donation, smoking status, paid maternity leave, baby's semester of life, use of pacifier, and bottle feeding (Table 3).

It is noteworthy that, during the care offered after the baby's birth, slightly over half of the mothers received information at the unit on milk expression and perceived the unit as a source of help for breastfeeding. Less than half of mothers were encouraged to donate breast milk, encouragement came most frequently from professionals at the PHCU. Over two-thirds of the nursing mothers did not have doubts or difficulties regarding the donation. Most babies were bottle-fed and a little less than 50% used a pacifier (Table 3).

In the multivariate analysis, the factors associated with breast milk donation were the intermediate variable hospitalization of the baby in a neonatal unit, and the proximal variables information on breast milk expression, having received help from the unit to breastfeed, and having been encouraged to donate breast milk (Table 4).

Adjusted prevalence ratios of human milk donation to primary health care units. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013.

| Variables | APR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admission at neonatal unit | |||

| Yes | 0.094 | 0.013–0.656 | 0.017 |

| No | 1 | ||

| Information on breast milk expression | |||

| Yes | 3.647 | 1.482–8.973 | 0.005 |

| No | 1 | ||

| Help at the unit to breastfeed | |||

| Yes | 2.238 | 1.199–4.178 | 0.011 |

| No | 1 | ||

| Was encouraged to donate breast milk | |||

| Yes | 7.057 | 3.037–16.400 | <0.001 |

| No | 1 | ||

Less than one-tenth of the mothers of children younger than 1 year cared by PHCUs had donated breast milk. The low prevalence of donation observed may be due to the still-incipient Expressed Human Milk Receiving Services program, which is still implementing actions to encourage donation and to collect breast milk at home.

Factors associated with the donation were related to the assistance received at the PHCUs, namely: information on breast milk expression, having been encouraged to donate breast milk, and having received help from the unit to breastfeed. One single factor was inversely associated with the donation, the hospitalization of the baby in a neonatal unit.

This is the first study to analyze factors associated with human milk donation by nursing mothers attended to at PHCUs, and having as the study sample the assisted population, and not only the donors. In a literature review on the practice of human milk donation and its determinants, only two analytical articles whose assessed populations consisted of human milk donors were retrieved: one investigated the factors associated with the regular donation of breast milk17 and the other analyzed the volume of milk donated to HMBs.18

Considering the only factor inversely associated with breast milk donation, hospitalization in a neonatal unit showed a 90% reduction in the prevalence of donation. The hospitalization of at-risk newborns negatively interferes with both the duration of breastfeeding19 and the time until the first breastfeeding,20 possibly because the sucking strength of a preterm baby or one born with a pathology is less intense than that of a baby born at term,21 decreasing the milk production stimulus. Additionally, it can be assumed that children who are admitted to a neonatal care unit may require more care than children born healthy, making mothers less available for breast milk donation.

Information on breast milk expression during the follow-up at primary health units is important for breastfeeding management, so that mothers can cope with breast engorgement or low breast milk production.22 A study conducted in Australia observed that nursing mothers who milk their breasts are less likely to discontinue breastfeeding before the baby is 6 months old.23 Similarly, the present study showed that teaching mothers how to express their milk was associated with an over three times higher practice of breast milk donation.

The help offered to the nursing mother was associated with a two-fold higher practice of breast milk donation. Therefore, help to breastfeed not only contributes to the woman feel more assured when breastfeeding,24 but also resulted in the donation of the excess breast milk produced. A qualitative study observed that, according to the mothers, breastfeeding support consists in actions available at the hospital, family, and workplace contexts and is a phenomenon that encompasses aspects of breastfeeding encouragement, promotion, and protection.25 A study aimed at understanding the meanings expressed by women users of PHCUs about the support received to breastfeed identified encouragement as positive support, as well as management and partnership support.26

The encouragement to donate was the factor most often associated with the practice of breast milk donation, possibly due to its effects on the mother's incentive to express her own breasts to store the milk for donation. However, although the interviews were carried out in units that had Breast milk expressed Receiving Service, less than half of the mothers had been encouraged to donate breast milk. Likewise, in a study carried out in the Federal District, the mothers declared the importance of having access to information on breastfeeding on their motivation, but few had been encouraged to donate.27

Proximal factors, such as age and maternal schooling, were not associated with breast milk donation, unlike results from studies conducted with donors for HMBs, where young age was associated with a higher volume of donated milk,18 and a higher degree of schooling was associated with regular donation of human milk.17 In the present study, the absence of an association with maternal schooling may be due to the homogeneity of the researched population as users of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]).

The limitations of the present study should be noted. The cross-sectional epidemiological design hinders the determination of temporal–causal associations between the investigated factors and the outcome. Some results may be overestimated due to the possibility of memory bias: women who were breast milk donors may remember more easily the incentive received at the unit for donation or help to breastfeed. It should also be noted that, in the present study, mothers were characterized as donors and non-donors, regardless of the frequency of donations and the volume of donated milk. Future studies exploring these aspects may bring new contributions to the subject.

It can be concluded that the previous admission of the infant to a neonatal unit had an inverse association with breast milk donation, and that the incentive, help, and information provided to the mothers were essential factors for breast milk donation, demonstrating the role of the PHCUs for the promotion of this practice.

Healthcare professionals in the primary health network should be trained in breastfeeding counseling courses,28 the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative.29 and/or the “Amamenta e Alimenta Brasil” Strategy.30 These training programs provide their participants with listening and learning skills to build trust and give support in breastfeeding management, as well as to develop appropriate workflows that can contribute not only to increase the duration of breastfeeding but also to promote breast milk donation. These practices would contribute to the attainment of the goal of a 15% increase in the volume of human milk collected for newborns at risk,11 as well as the reduction in neonatal mortality.9

FundingFAPERJ, process n. E-26/111.508/20.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Meneses TM, Oliveira MI, Boccolini CS. Prevalence and factors associated with breast milk donation in banks that receive human milk in primary health care units. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:382–8.

Study carried out at Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF), Niterói, RJ, Brazil.