To find evidence of the symptoms of anxiety/depression in children with developmental coordination disorder as compared to their typically developing peers at both the group and individual level, and to identify how many different tools are used to measure anxiety and/or depression.

MethodsElectronic searches in eight databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, PsycINFO, Embase, SciELO and LILACS), using the following keywords: ‘Developmental Coordination Disorder,’ ‘Behavioral Problems,’ ‘Child,’ ‘Anxiety,’ ‘Depression,’ ‘Mental Health,’ and ‘Mental Disorders.’ The methodological quality was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies and the NOS for cohort studies. The studies were classified as low, moderate, or high quality. To provide clinical evidence, the effect size of the symptoms of anxiety and depression was calculated for each study.

ResultsThe initial database searches identified 581 studies, and after the eligibility criteria were applied, six studies were included in the review. All studies were classified as being of moderate to high quality, and the effect sizes for both anxiety and depression outcomes were medium. The evidence indicated that all of the assessed studies presented more symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with developmental coordination disorder than in their typically developing peers. On the individual level, this review found children with clinical symptoms of anxiety in 17–34% (developmental coordination disorder) and 0–23% (typically developing), and of depression in 9–15% (developmental coordination disorder) and 2–5% (typically developing) of the children.

ConclusionsChildren with developmental coordination disorder are at higher risk of developing symptoms of anxiety and depression than their typically developing peers.

Encontrar evidências dos sintomas de ansiedade/depressão em crianças com transtorno do desenvolvimento da coordenação em comparação com seus pares com desenvolvimento típico, a nível individual bem como em grupo, e identificar quantas ferramentas diferentes são utilizadas para medir a ansiedade e/ou depressão.

MétodosPesquisa eletrônica em oito bases de dados (PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, Eric, PsycINFO, Embase, Scielo e Lilacs), utilizando as seguintes palavras-chave: ‘Developmental Coordination Disorder’, ‘Behavioral Problems’, ‘Child’, ‘Anxiety’, ‘Depression’, ‘Mental Health’ e ‘MentalDisorders’. A qualidade metodológica foi avaliada pela escala de Newcastle-Ottawa (NOS) adaptada para estudos transversais e pela escala de Newcastle-Ottawa (NOS) para estudos de coorte. Os estudos foram classificados em: qualidade baixa, moderada e alta. Para fornecer evidência clínica, o tamanho do efeito dos sintomas de ansiedade e depressão foi calculado para cada estudo.

ResultadosAs buscas iniciais nas bases de dados identificaram 581 estudos e, após a aplicação dos critérios de elegibilidade, seis estudos foram incluídos na revisão. Todos os estudos foram classificados como tendo qualidade moderada a alta e os tamanhos do efeito para os desfechos de ansiedade e depressão foram médios. As evidências indicaram que 100% dos estudos avaliados apresentaram mais sintomas de ansiedade e depressão em crianças com transtorno do desenvolvimento da coordenação do que em seus pares com desenvolvimento típico. No nível individual, encontramos crianças com sintomas clínicos de ansiedade em 17-34% (transtorno do desenvolvimento da coordenação) e 0-23% (desenvolvimento típico) e de depressão em 9-15% (transtorno do desenvolvimento da coordenação) e 2-5% (desenvolvimento típico) das crianças.

ConclusõesCrianças com transtorno do desenvolvimento da coordenação apresentam maior risco de desenvolver sintomas de ansiedade e depressão do que seus pares com desenvolvimento típico.

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) is a specific motor delay characterized by significant difficulties with motor skills; it is typically associated with poor balance, coordination, and handwriting.1 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 5th edition (DSM-5), the identification of DCD is composed of four criteria. These criteria are subsequently: (A) motor skills performance is substantially below the level which can be expected considering the chronological age of the child; (B) motor skills interfere with activities of daily living at home and at school; (C) the symptoms were present at an early age; (D) the motor problems are not explained by intellectual, medical, or neurological conditions.1 DCD is one of the most prevalent motor disorders, affecting about 6% of school-age children2–4 and persisting to adulthood.5

Significantly lower motor skills have been found to interfere with the individual activities of daily living,6 making the execution of movements significantly challenging.7,8 The gaps in motor skills possessed by children with DCD decrease their participation in sports and regular physical activities.9 In addition, children with DCD report more difficulties with self-care, which can interfere with their participation at school, on the playground, and at home,10 which in turn can cause social isolation that decreases their sense of self-worth.11

Low self-esteem is only one of the factors that can lead to increased symptoms of anxiety and depression.12 Anxiety is defined as “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like increased blood pressure”,1 while stressful life events predict periods of depression,13,14 of which – amongst others – symptoms of reduced interest or pleasure in activities previously enjoyed, and delayed psychomotor skills are presented. Considered a multifactorial disorder, the etiology is affected by the genetic and environmental context, which can influence the normal cycle of development in children.15 The present study aimed at analyzing data regarding symptoms of anxiety and depression from screening tests, which signal the presence of more anxious or depressed feelings that meet the clinical criteria of a disorder.16

Missiuna et al.12 studied children who had DCD combined with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and found that they had more symptoms of anxiety and depression than their peers who had typical development. Lingam et al.17 identified more risk for both physical and mental health problems in a population with DCD. Assuming that children with DCD widely present a profile of vulnerability due to these potential mediators combined with more exposure to contributory factors for increased symptoms of depression and anxiety, it was hypothesized that children with DCD or probable DCD have significantly more symptoms of anxiety/depression than their typically developing (TD) peers. Therefore, the present systematic review study aimed to find evidence of symptoms of anxiety/depression in children with DCD compared to their TD peers at both the group and individual level, and to identify how many different tools are used to measure anxiety and/or depression.

MethodsThe methodology of this systematic review was developed using the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook.18 The review's protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database using ID number CRD42018091859.

Database and keywordsInitial searches were done by two independent reviewers. The searches were conducted in the following databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, PsycINFO, Embase, SciELO, and LILACS, using the following keywords from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database: ‘Developmental Coordination Disorder,’ ‘Behavioral Problems,’ ‘Child,’ ‘Anxiety,’ ‘Depression,’ ‘Mental Health,’ and ‘Mental Disorders.’ To optimize the results, five combinations of these keywords were created by using the Boolean AND operator: Developmental Coordination Disorder AND Anxiety AND Child; Developmental Coordination Disorder AND Mental Health AND Child; Developmental Coordination Disorder AND Depression AND Child; Developmental Coordination Disorder AND Behavioral Problems AND Child; Developmental Coordination Disorder AND Mental Disorders AND Child.

Eligibility criteriaArticles were selected by fulfilling all the following criteria: (1) Original research conducted with children with DCD or any other terms used regarding DCD, such as children with probable DCD or at risk for DCD, and published in English between January 1, 2007 and November 25, 2018. (2) The diagnostic criteria for identifying children with DCD was based on the DSM-IV or the DSM-5, which is composed of four criteria.1,19 These criteria are subsequently: (A) motor skills performance is substantially below the level which can be expected considering the chronological age of the child; (B) motor skills interfere with activities of daily living at home and at school; (C) the symptoms were present at an early age; (D) the motor problems are not explained by intellectual, medical, or neurological conditions. The children needed to fulfill at least the criteria A and B of the DSM-5.1 (3) Studies that assessed symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. (4) Studies that assessed symptoms of anxiety and/or depression using specific tests, scales, questionnaires, or other standardized instruments. (5) Original studies using any design except case studies and reviews. (6) Studies that used control groups of TD children.

Data extraction and analysisThe study's data selection began with the initial search and then the removal of all duplicates. To make the initial selections, two independent reviewers (L.A.R. and T.T.G.D.) screened the study titles. Next, the abstracts of the selected articles were assessed. Then, the full texts of the articles that remained were assessed, and those meeting the eligibility criteria were included in the review. Discrepancies and disagreements among the authors were solved by consensus with a third reviewer (J.L.C.N.).

The main results were summarized using the following four categories: (1) participants (age, sample size, comparison groups, and inclusion criteria for DCD); (2) outcomes (symptoms of anxiety and depression); (3) instrument assessment; and (4) methodological quality.

To assess the effects of the anxiety and depression outcomes of DCD children in clinical practice, the effect sizes based on Cohen's d20 were calculated, using the following reference values: small effect size (d=0.20–0.30); medium effect size (d=0.40–0.70), and large effect size (d=≥0.80). To calculate the effect sizes of the differences between the groups, this review used the difference between the means divided by the standard deviations presented in each study for each outcome (symptoms of anxiety and depression). When the authors did not show these values in the manuscript, that study was excluded from the effect sizes analyses.

The individual outcomes of children scoring within the clinical range of the used measurement tools for anxiety and/or depression are reported in percentages within each group (DCD vs. TD), when reported.

The methodological quality was determined by three independent reviewers, and differences were discussed and solved by consensus. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies and NOS for cohort studies21 were used.

The NOS uses a system of stars for scoring the articles, considering specific criteria. Cohort studies could score a maximum of four stars for the selection criteria, two stars for the comparability criteria, and three stars for the outcome criteria, totaling a maximum of nine stars. The authors considered the studies as high quality when they scored ≥7 stars and moderate quality as 5–6 stars, according the classification adopted by Xing et al.22

Regarding cross-sectional studies, a maximum of five stars was scored for the selection criteria, three stars for the comparability criteria, and two stars for the outcome criteria, totaling a maximum of ten stars. The criteria adopted by Wang et al.23 were used to classify the cross-sectional studies, who considered low-quality scores as 0–4, moderate-quality scores as 5–6, and high-quality scores as ≥7.

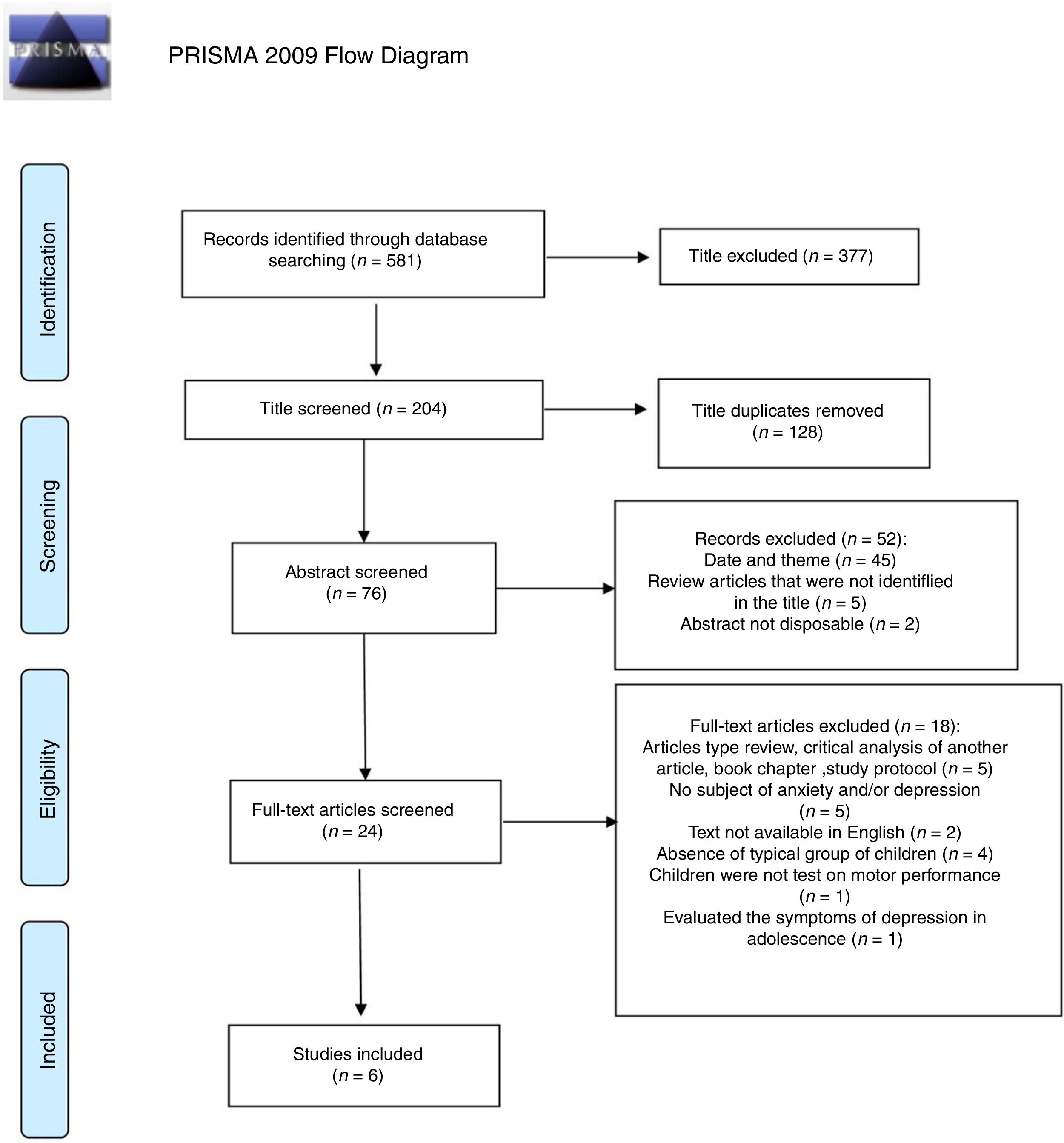

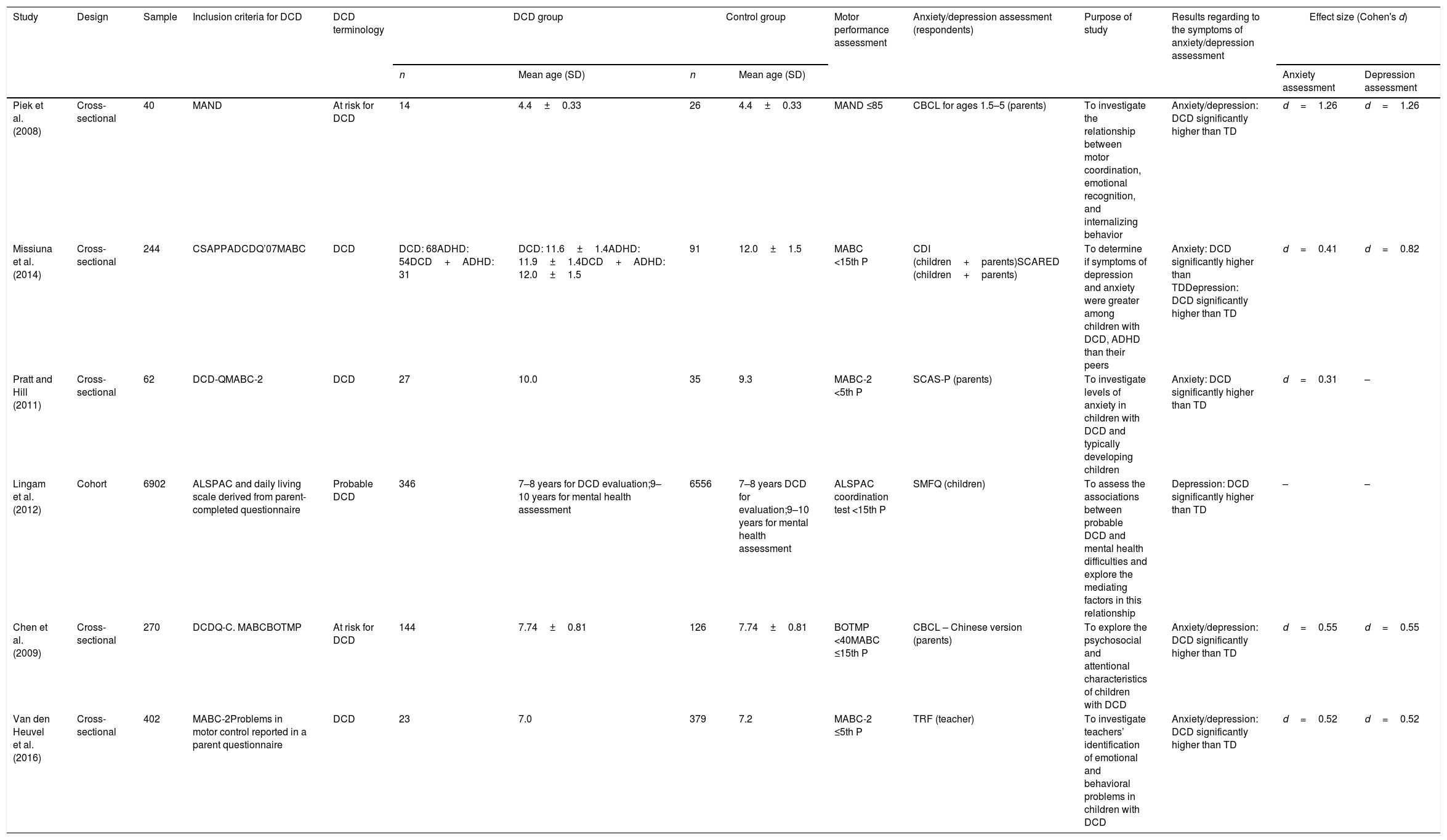

ResultsThe initial database searches identified 581 studies, of which six studies met all eligibility criteria (Fig. 1).24 Five articles were cross-sectional studies, and one was a cohort study. The cumulative sample size of all the included studies was 7920 children (653 with DCD, 7213 TD peers, and 54 with ADHD – who were not considered in these analyses). The participants’ ages ranged from 4 years and 4 months to 11 years and 6 months (Table 1).

Flowchart showing the steps in the systematic review.24

Summary of results from the studies included.

| Study | Design | Sample | Inclusion criteria for DCD | DCD terminology | DCD group | Control group | Motor performance assessment | Anxiety/depression assessment (respondents) | Purpose of study | Results regarding to the symptoms of anxiety/depression assessment | Effect size (Cohen's d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean age (SD) | n | Mean age (SD) | Anxiety assessment | Depression assessment | |||||||||

| Piek et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | 40 | MAND | At risk for DCD | 14 | 4.4±0.33 | 26 | 4.4±0.33 | MAND ≤85 | CBCL for ages 1.5–5 (parents) | To investigate the relationship between motor coordination, emotional recognition, and internalizing behavior | Anxiety/depression: DCD significantly higher than TD | d=1.26 | d=1.26 |

| Missiuna et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | 244 | CSAPPADCDQ’07MABC | DCD | DCD: 68ADHD: 54DCD+ADHD: 31 | DCD: 11.6±1.4ADHD: 11.9±1.4DCD+ADHD: 12.0±1.5 | 91 | 12.0±1.5 | MABC <15th P | CDI (children+parents)SCARED (children+parents) | To determine if symptoms of depression and anxiety were greater among children with DCD, ADHD than their peers | Anxiety: DCD significantly higher than TDDepression: DCD significantly higher than TD | d=0.41 | d=0.82 |

| Pratt and Hill (2011) | Cross-sectional | 62 | DCD-QMABC-2 | DCD | 27 | 10.0 | 35 | 9.3 | MABC-2 <5th P | SCAS-P (parents) | To investigate levels of anxiety in children with DCD and typically developing children | Anxiety: DCD significantly higher than TD | d=0.31 | – |

| Lingam et al. (2012) | Cohort | 6902 | ALSPAC and daily living scale derived from parent-completed questionnaire | Probable DCD | 346 | 7–8 years for DCD evaluation;9–10 years for mental health assessment | 6556 | 7–8 years DCD for evaluation;9–10 years for mental health assessment | ALSPAC coordination test <15th P | SMFQ (children) | To assess the associations between probable DCD and mental health difficulties and explore the mediating factors in this relationship | Depression: DCD significantly higher than TD | – | – |

| Chen et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional | 270 | DCDQ-C. MABCBOTMP | At risk for DCD | 144 | 7.74±0.81 | 126 | 7.74±0.81 | BOTMP <40MABC ≤15th P | CBCL – Chinese version (parents) | To explore the psychosocial and attentional characteristics of children with DCD | Anxiety/depression: DCD significantly higher than TD | d=0.55 | d=0.55 |

| Van den Heuvel et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | 402 | MABC-2Problems in motor control reported in a parent questionnaire | DCD | 23 | 7.0 | 379 | 7.2 | MABC-2 ≤5th P | TRF (teacher) | To investigate teachers’ identification of emotional and behavioral problems in children with DCD | Anxiety/depression: DCD significantly higher than TD | d=0.52 | d=0.52 |

DCD, developmental coordination disorder; TD, typical developmental; SD, Standard Deviation; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; MAND, McCarron Assessment of Neuromuscular Development; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CDI, Children's Depression Inventory; SCARED, Self-report for Childhood Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders; MABC, Movement Assessment Battery for Children; CSAPPA, Children's Self-Perceptions of Adequacy in Predilection for Physical Activity Scale; DCDQ, Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire; SCAS, Spence Children's Anxiety Scale; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; BOTMP, Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency; TRF, Teacher's Report Form.

The body of evidence from the six studies indicated significantly more symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD than in their TD peers. In five of the six studies, the effect sizes could be calculated for symptoms of anxiety12,25–28 and symptoms of depression.12,24,27,28 All included studies reported similar results of increased symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD compared with their typical peers (Table 1).

In the included studies, the DSM 5 criteria A and B were the most commonly considered criteria, evaluating motor performance and interference of coordination difficulties in academic achievement or daily life activities, respectively.

To evaluate motor performance assessment (criteria A), 67% of the studies (n=4)12,26–28 included used the Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC) with ≤15th percentile, or the MABC-2 with ≤5th percentile to indicate DCD; one27 of them also used the Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP) with a cut-off standard score of <40 for DCD. One study17 used the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Coordination Test with a score <15th percentile, and one study25 used the McCarron Assessment of Neuromuscular Development (MAND) with a score ≤85 indicating DCD.

To evaluate criteria B, three of the six studies12,26,27 included used the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ) and two studies17,28 analyzed the reported outcomes of a parent questionnaire.

The studies used ambiguous terminology to refer to the children with DCD. Of the six studies included, three used DCD, two at risk for DCD, and one probable DCD.

Various instruments were used to assess the children's mental-health outcomes, but the most commonly used was the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (n=2).25,27 Furthermore, Children's Depression Inventory (CDI)12 and the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ)17 scored by children were used to measure depression. The Self-report for Childhood Anxiety and Related Disorders (SCARED)12 scored by children and the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale Parental version (SCAS-P)26 scored by parents were used to measure anxiety. The Teacher's Report Form (TRF)28 was used by teachers to score the emotional and behavioral problems of the children.

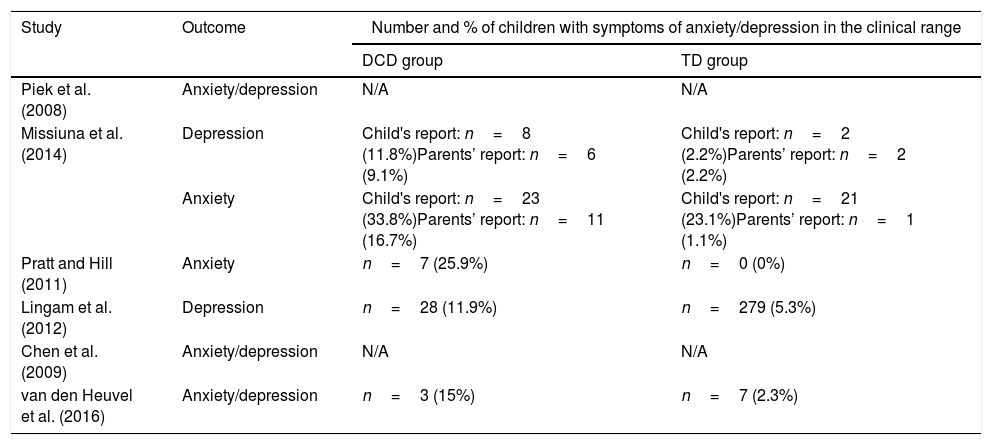

At an individual level, presented in Table 2, the results of the studies included in this review infer that a percentage of children with DCD have a higher probability of presenting symptoms of anxiety or depression in the clinical range when compared to children with typically development.

Number and percentage of children with symptoms of anxiety/depression.

| Study | Outcome | Number and % of children with symptoms of anxiety/depression in the clinical range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCD group | TD group | ||

| Piek et al. (2008) | Anxiety/depression | N/A | N/A |

| Missiuna et al. (2014) | Depression | Child's report: n=8 (11.8%)Parents’ report: n=6 (9.1%) | Child's report: n=2 (2.2%)Parents’ report: n=2 (2.2%) |

| Anxiety | Child's report: n=23 (33.8%)Parents’ report: n=11 (16.7%) | Child's report: n=21 (23.1%)Parents’ report: n=1 (1.1%) | |

| Pratt and Hill (2011) | Anxiety | n=7 (25.9%) | n=0 (0%) |

| Lingam et al. (2012) | Depression | n=28 (11.9%) | n=279 (5.3%) |

| Chen et al. (2009) | Anxiety/depression | N/A | N/A |

| van den Heuvel et al. (2016) | Anxiety/depression | n=3 (15%) | n=7 (2.3%) |

N/A, no individual information data was presentedt; DCD: Developmental Coordination Disorder; TD: Typically Developing.

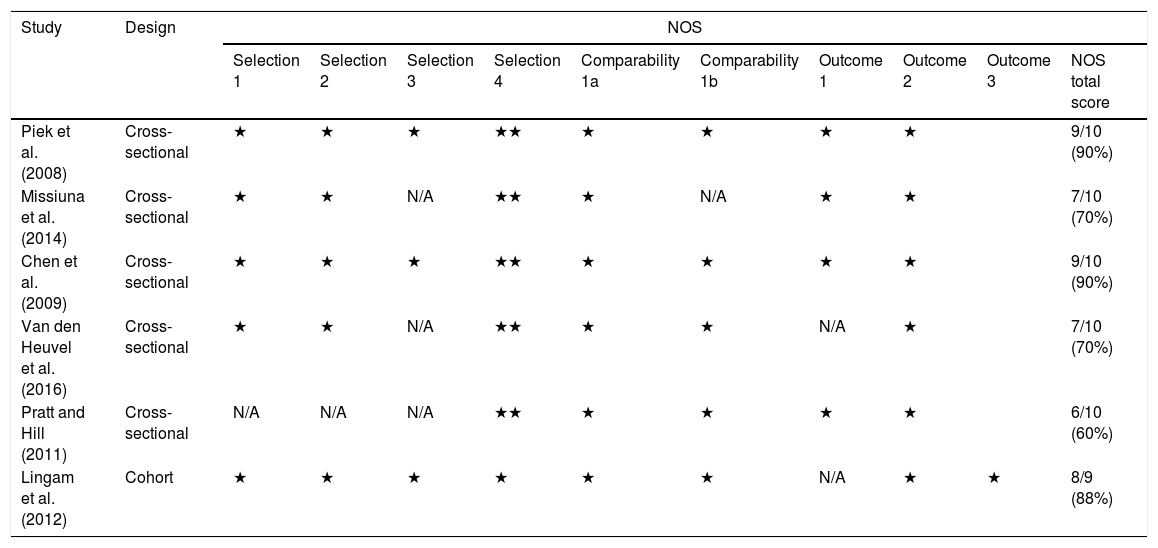

The methodological quality of the included studies was classified as high quality in five articles. Two of them reaching 90% of methodological criteria,25,27 one study reached, 88%,17 and two reached 70% of the criteria.12,28 One study was of moderate quality, reaching 60% of the criteria.26

None of the cross-sectional studies, evaluated by the NOS adapted for cross-sectional studies, scored two stars on outcome criterion 1 (independent blind evaluation or analysis by registry). However, the six studies (five cross-sectional and one cohort) scored on the criterion “controls the most important factor” (comparability A, one star). All details are displayed in Table 3.

Study quality assessment using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional and cohort studies.

| Study | Design | NOS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection 1 | Selection 2 | Selection 3 | Selection 4 | Comparability 1a | Comparability 1b | Outcome 1 | Outcome 2 | Outcome 3 | NOS total score | ||

| Piek et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9/10 (90%) | |

| Missiuna et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | ★ | ★ | N/A | ★★ | ★ | N/A | ★ | ★ | 7/10 (70%) | |

| Chen et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 9/10 (90%) | |

| Van den Heuvel et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional | ★ | ★ | N/A | ★★ | ★ | ★ | N/A | ★ | 7/10 (70%) | |

| Pratt and Hill (2011) | Cross-sectional | N/A | N/A | N/A | ★★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 6/10 (60%) | |

| Lingam et al. (2012) | Cohort | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | N/A | ★ | ★ | 8/9 (88%) |

NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; NA, not available.

The present review compiled evidence from six articles that assessed symptoms of anxiety and/or depression in children with DCD as compared with symptoms in TD peer controls. The results showed that in all studies evidence was found for increased presence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD compared to TD children, supporting the hypothesis of this study.

Piek et al.,25 Chen et al.,27 and van den Heuvel et al.28 showed that anxiety and depression in DCD is significantly higher than in TD children. Children's motor coordination ability was negatively associated with reported anxious-depressed behavior, so when the children scored poorly in coordination, more anxiety/depression was reported by parents.25 However, of this group, no individual child was reported as scoring in the clinical range of anxious/depressive behavior.25,27 This is an important finding to report, since this means that there was no causality found for DCD resulting in clinical symptoms of anxiety and depression. It only brings forward that children with DCD have more vulnerability factors that may lead to increased symptoms of anxiety and depression in some of the children. In van den Heuvel et al.,28 anxiety and depression were part of an emotional and behavior problems scale that involves other emotional problems; 15% of the DCD children presented a clinical TRF in the DCD group compared to the TD children.

Missiuna et al.12 and Lingam et al.17 found similar results of significant differences between children with DCD compared to TD children regarding depression. Based on these results, similar percentages of individual children were observed who scored within the clinical range by both children with DCD and parents (11.8% and 11.9%, respectively) for children12,17 and 9.1% for parents,12 even though they were measured by different tools. Again, this only demonstrates that a minority of children with DCD would feel more depressed compared to their peers. More information is needed regarding self-esteem, social lifestyle, academic scores, and support of parents and/or teachers in order to understand more of the processes leading to symptoms of depression.

Missiuna et al.12 and Pratt and Hill26 showed significant differences between children with DCD compared to TD children regarding anxiety. But the mean of the SCARED responded to by parents and children did not reach the clinical range. However, 16.7% of parents and 33.8% of children from the DCD group scored positive for clinical symptoms of anxiety. Pratt and Hill26 showed similar percentages of individual children that scored within the clinical range; 25.9% DCD children reported symptoms of anxiety. It is of interest to gain more understanding regarding why parents score their children lower in symptoms of anxiety than the children themselves.

The effect size could be calculated for five out of six studies included in this review. Considering these studies (n=5 for symptoms of anxiety and n=4 for symptoms of depression, assuming that in two studies both outcomes were evaluated together) the mean of calculated effect size for symptoms of anxiety was d=0.61, while for symptoms of depression it was d=0.78, indicating a medium effect size for the clinical implications of both symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD. This means that DCD is not a fully contributing factor to the presence of symptoms of anxiety or depression. In fact, a considerable number of children with DCD may not develop symptoms of anxiety or depression. Other factors, like the factors put forward in the study by Lingam et al.17 of low verbal IQ, poor social communication, being a victim, low self-esteem, and poor scholastic competence may contribute even more. Further research is needed to disentangle the relationship between the motor competence of children with DCD, the history of treatment and support, and the effects on self-esteem, social communication, and isolation, preferably in different cultures.

Given the current diagnostic criteria for identifying children with DCD based on DSM-5,1 it is possible to infer that each of the four criteria takes the child's daily life and his or her opportunities for practice into account. In addition, it can be inferred that, in addition to opportunities for practice, children should be surrounded by psychosocial protective factors, including positive social support from family, friends, and teachers. This support must be adequate to promote the encouragement that these children need to try to overcome their motor deficits and/or become socially more involved and minimize their risk for anxiety and depression. They can be clumsy, but can build up sufficient social relationships with their peers.

From this review, it is clear that anxiety and/or depression are measured inconsistently by different tools, i.e., six different tools were used and were completed by different respondents. So far, it is unclear whether parental or teacher scores of mental health items correspond with the experienced feelings of the children. Some issues should be noted regarding the differences between the symptoms of anxiety and depression. For example, whereas anxiety includes excessive worry about future actions combined with tension or stress, depression is characterized by low self-esteem, mood disturbance or dysregulation, and sadness.1 Often, both conditions frequently co-occur12 in the same period or sequentially and, overtime, an increase of the presence of both conditions is seen29; therefore, assessments for both conditions are often conducted together, particularly in non-clinical studies. Given this, four of the six studies included in the present review assessed both anxiety and depression in children with DCD and peer control groups.12,25,27,28 One study26 assessed only anxiety, and another one17 assessed only depression. Taking into consideration that symptoms of anxiety and depression are composed of different characteristics,29 it is possible to induce a bias when both assessments are performed by the same instrument. On the other hand, for research purposes the researchers can save time and resources using only one standardized questionnaire for screening symptoms of both anxiety and depression. However, more additional detailed information is needed when a child scores ‘at risk.’

It is important to realize that deprivation, in this case children who are not exposed to practice motor skills or have an active lifestyle in early childhood, may lead to neurodevelopmental problems, which can be related to symptoms of depression in adolescence.30 Therefore, besides motor performance level, the context of the child regarding parenthood, environment, and social economic status can give a better overview regarding factors that may predict symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Further research is needed to determine which factors play the most important role to become ‘at risk’ for psychological problems.

All cross-sectional studies scored on the selection criterion 4 (validated assessments), thus it can be concluded that the studies included in this review strictly followed the recommended criteria for studies with this design, avoiding possible biases. This is also appropriate for criterion 2, which refers to statistical tests used for analysis, reinforcing that those were appropriate to demonstrate the relevance of the results. Besides the NOS cross-sectional, none of the selected studies scored two stars on the outcome criterion 1, corresponding to independent blind evaluation or analysis by registry. This lack of fulfilling independent blind evaluation or analysis by registry (also criterion 1 for cohort studies) infers that for this outcome of anxiety and/or depression symptoms, the use of self-completed questionnaires seemed to be a questionable choice, since the evaluation is done by an interviewer who may have had a direct influence on the respondent's response. To avoid the tendency to give overly positive self-descriptions, self-report questionnaires without the influence of an interviewer could be used to minimize socially desirable responses (SDR),31 or self-report questionnaires answered by parents or teachers.

The findings of the present review both support the importance of investigating the psychosocial aspects of children with DCD and reinforce the recommendations of the European Academy for Childhood Disability (EACD) regarding clinical practice in children with DCD.32 The entire process of evaluation and intervention must involve not only the motor aspects, but also personal and individual factors, and should include a review of all items present in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).33 In fact, evaluations and interventions that focus on the indicative symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD correspond to the personal and environmental factors of the ICF. In addition, considering the multifactorial aspects, improvements in these psychosocial cues can improve the structure and function of the body and participation in daily activities. Thus, the results of the present review support the importance of considering the indicative symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD.

To avoid confusion when studies are compared, researchers and therapists must be aware of the terms in the current literature. The authors encourage researchers to follow the classification based on Smits-Engelsman et al.,34 which consider the DSM-5 criteria to be described and observed using standardized assessments, and also the children's age.

This systematic review has some limitations. The various designs adopted by the included studies resulted in various interpretations of their findings. Notably, the cohort study was capable of evaluating the relationships between causes and effects, and the cross-sectional studies were not. Furthermore, the variety of sample sizes, instruments used to assess motor performance, and the psychosocial outcomes of interest (anxiety and depression) may have affected interpretation of the studies’ results. However, regarding the outcomes of interest, higher risks of symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with DCD were found in all studies included in the review.

ConclusionsChildren with DCD appear to be at increased risk of presenting symptoms of anxiety and/or depression than children with typical development. This implies that the effect of motor problems may be facilitating an increased risk for symptoms of anxiety and/or depression, even though this is not the case for all children. Clinicians have to be aware of these risks and may consider extending their assessments to questionnaires aimed to measure symptoms of anxiety or depression. If more attention is paid to these symptoms and children are measured more consistently, more knowledge will be gained regarding the mediating effects of motor problems on symptoms of anxiety and depression.

FundingThe authors would like to thank the financial support from Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel(CAPES).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Draghi TT, Cavalcante Neto JL, Rohr LA, Jelsma LD, Tudella E. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with developmental coordination disorder: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96:8–19.