To review the association between intimate partner violence and breastfeeding practices in the literature.

Data sourcesThe search was carried out in five databases, including MEDLINE, LILACS, SCOPUS, PsycoINFO, and Science Direct. The search strategy was carried out in February 2017. The authors included original studies with observational design, which investigated forms of intimate partner violence (including emotional, physical, and/or sexual) and breastfeeding practices. The quality of the studies was assessed based on the bias susceptibility through criteria specifically developed for this review.

Summary of dataThe study included 12 original articles (10 cross-sectional, one case-control, and one cohort study) carried out in different countries. The forms of intimate partner violence observed were emotional, physical, and/or sexual. Breastfeeding was investigated by different tools and only assessed children between 2 days and 6 months of life. Of the 12 studies included in this review, eight found a lower breastfeeding intention, breastfeeding initiation, and exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of the child's life, and a higher likelihood of early termination of exclusive breastfeeding among women living at home where violence was present. The quality varied between the studies and six were classified as having low bias susceptibility based on the assessed items.

ConclusionsIntimate partner violence is associated with inadequate breastfeeding practices of children aged 2 days to 6 months of life.

Revisar na literatura a associação da violência entre parceiros íntimos e as práticas de aleitamento materno.

Fontes dos dadosForam utilizadas para as buscas cinco bases de dados, incluindo o MEDLINE, LILACS, SCOPUS, PsycoINFO e Science Direct. A estratégia de busca foi realizada em fevereiro de 2017. Foram incluídos estudos originais com desenho observacional, os quais investigaram formas de violência entre parceiros íntimos: emocional, física e/ou sexual e as práticas de aleitamento materno. A qualidade dos estudos foi avaliada a partir da susceptibilidade a vieses por critérios especificamente desenvolvidos para esta revisão.

Síntese dos dadosForam incluídos 12 artigos originais (10 seccionais, 1 caso-controle e 1 coorte) realizados em diferentes países. As formas de violência entre parceiros íntimos observadas foram emocional, física e/ou sexual. O aleitamento materno investigado nos estudos se fez por diferentes instrumentos e avaliaram apenas crianças entre dois dias e seis meses de vida. Dos doze estudos incluídos nesta revisão, oito encontraram menor chance de intenção de amamentar, menor chance de iniciação ao aleitamento materno e de amamentação exclusiva durante os primeiros seis meses de vida da criança e maior probabilidade de interrupção precoce do aleitamento materno exclusivo entre as mulheres que viviam em domicílios onde a violência estava presente. A qualidade variou entre os estudos e seis foram classificados apresentando baixa suscetibilidade ao viés a partir dos itens julgados.

ConclusõesA violência entre parceiros íntimos está relacionada às práticas inadequadas de aleitamento materno de crianças entre dois dias e seis meses de vida.

Breastmilk is unquestionably the ideal food for the healthy growth and development of children.1,2 The World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommend the early start of breastfeeding within one hour after birth, that children receive breastmilk exclusively during the first six months of life, and that breastfeeding be supplemented by other foods up to 2 years of age or more.2,3

Adequate breastfeeding is so critical that it could prevent the deaths of more than 800,000 children under 5 years of age a year; nonetheless, data show that no more than 37% of children worldwide are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life.4,5 Furthermore, a longer breastfeeding duration also contributes to the health and well-being of mothers, reducing the risk of ovarian and breast cancer and helping to prevent pregnancy during this period.5

The literature emphasizes the immediate and long-term consequences related to the early termination of exclusive breastfeeding and the short duration of breastfeeding. These inadequate practices may be associated with overweight and obesity in childhood, as well as low birth weight in children under 5 years, one of the leading causes of death worldwide.2,6–8

Breastfeeding practices (BFP), such as the decision to start or not breastfeeding, offer breast milk or formula, as well as the duration of breastfeeding, can be influenced by many factors such as birth weight, maternal age, level of schooling, socioeconomic status, income, maternal stress and depressive symptoms, social support, social network, parents’ diets, and the living environment.9–12

Studies also show that, in violent domestic environments, the quality of mothering and the ability of both parents to cope with the child's needs are impaired.13–15 Consequently, the ability to care for the child's feeding is also affected.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as the intentional use of physical force, emotional and sexual abuse, or use of power against an intimate partner, and has been indicated in recent studies as one more factor associated with inadequate BFP.16,17

The literature on the subject is still scarce and the results of the investigations are contradictory. Some studies show there is an association between IPV and breastfeeding, while others have not found statistically significant associations.16–19 Problems in the methodologies adopted by the studies may be an explanation for these divergent results; however, for a better understanding of the association between IPV and breastfeeding, and for the implementation of new studies, it is necessary to increase the knowledge on this phenomenon.19–22

Thus, the objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the existing evidence on the association between IPV and BFP during the first year of the child's life.

MethodsThis study was based on the Guidelines for Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies (MOOSE) and procedures for systematic reviews by Systematic Reviews by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).23,24 The present study was not registered in any systematic review database.

Eligibility criteriaThe studies included in this review were limited to original observational studies that assessed the association between IPV and BFP. Articles that focused on special population groups, such as those with HIV and eating disorders, were not included in this review. Studies that did not assess the association of IPV and BFP through association measures were excluded.

Definition and exposure measurement (IPV)This review considered different forms of IPV, including physical violence, emotional violence, sexual violence, or any combination of the three forms. It considered the men's violence against women, as well as women's violence against men. The periods considered for IPV assessment were: during the current pregnancy, during previous pregnancies, in the postpartum period, in the current relationship, in previous relationships, at any moment of life, and/or in the year prior to the interview.

Outcome definition and measurement – Breastfeeding practices (BFP)BFP considered for this review were: intention to breastfeed, when the woman showed interest in offering breastmilk still during pregnancy; start of breastfeeding, that is, whether the mother offered breastmilk in the postpartum period; exclusive breastfeeding, defined as exclusive offer of breast milk to the child; breastfeeding duration, expressed in days or months during which breast milk was offered to the child; early termination of exclusive breastfeeding, when, in addition to breast milk, other fluids and/or foods are offered to a child before the age of six months; predominant breastfeeding, when the child received, in addition to breast milk, water-based fluids such as water, teas and juices; and other BFP investigated by the studies.25

Search strategyThe search was carried out in five databases, including MEDLINE, LILACS, SCOPUS, PsycoINFO, and Science Direct. The search strategy was carried out in February 2017. The following MeSH terms (domestic violence OR spouse abuse OR intimate partner violence) AND (breast feeding OR breastfeeding OR Milk, Human) were combined with filters for observational studies. No language or date restrictions were applied for the inclusion.

Selection criteriaAfter duplicate removal, the selection of titles and abstracts was carried out independently by two researchers (MR and FM) to evaluate complete records, following a previously established research strategy.

Data extractionThe data were independently extracted by two authors (MR and FM) using a data collection form according to PRISMA criteria.24 Items extracted from each article were compiled into a table using Excel (Microsoft®, WA, USA) and included country, year of publication, study design, exposure and outcome variables, and data collection tools.

Bias susceptibilityBias susceptibility was assessed using a standard form for the evaluation of observational studies specifically developed for this review. A list of individual items included BFP analysis, IPV analysis, and tools for measuring IPV and BFP. Furthermore, the following variables were evaluated: confounding variable control, eligibility criteria for the participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, losses, and reverse causality for cross-sectional articles. The form was developed based on the criteria of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)26 and the literature, with the main objective of evaluating the external and internal validity of the different types of studies included in this review.

The answers to the “yes” (+) or “no” (−) items indicated that the information was considered or not considered, respectively; “partially” (±) was considered when part of the criterion was met and (?) was used when the information was not clear enough.

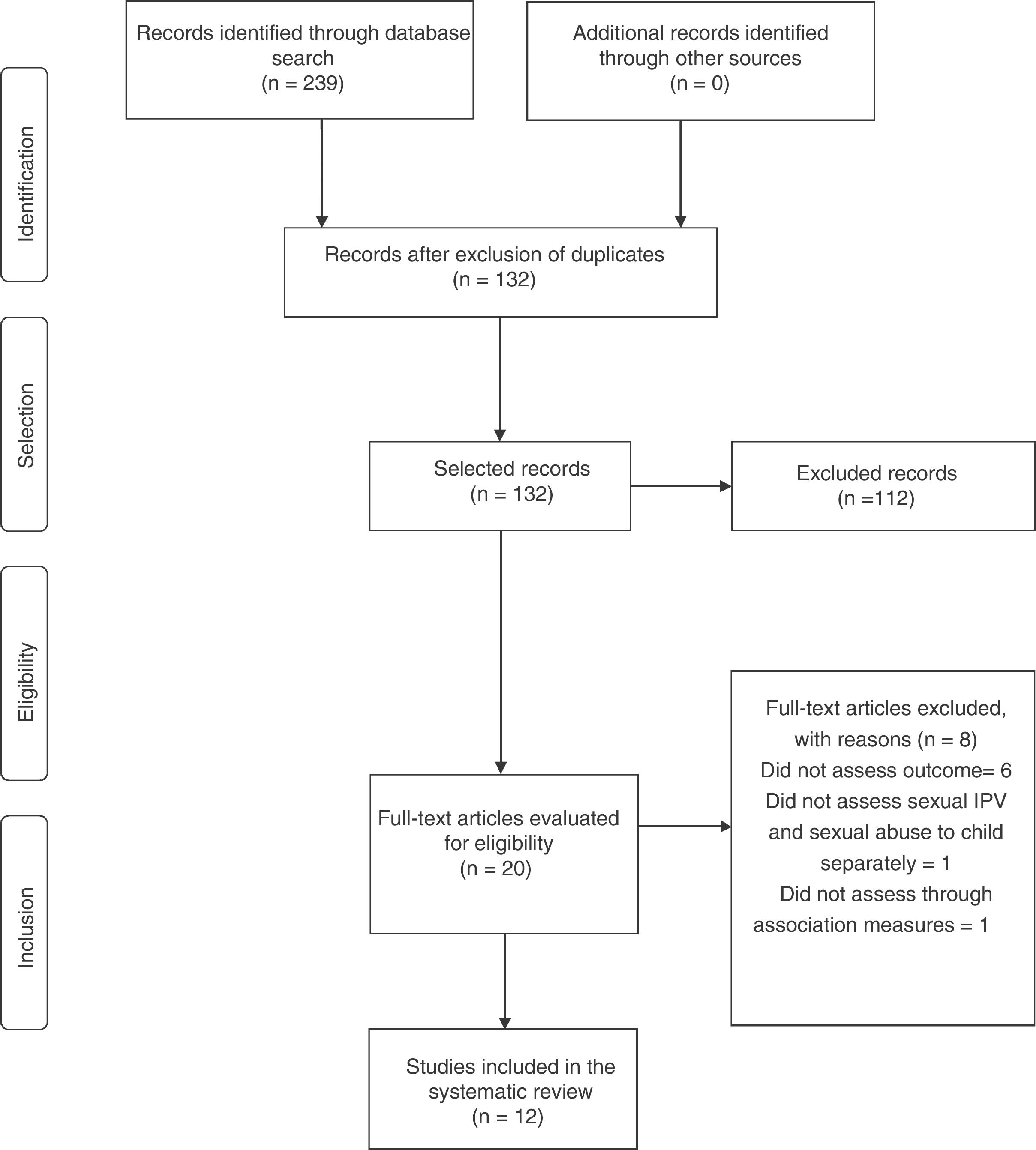

ResultsThe search resulted in a total of 239 articles. After the exclusion of the duplicates, 132 articles were selected for the reading of the titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 20 articles were selected for reading in full. A total of 12 studies were identified for inclusion in the review.16–19,27–34Fig. 1 shows the flow chart of the study selection process.

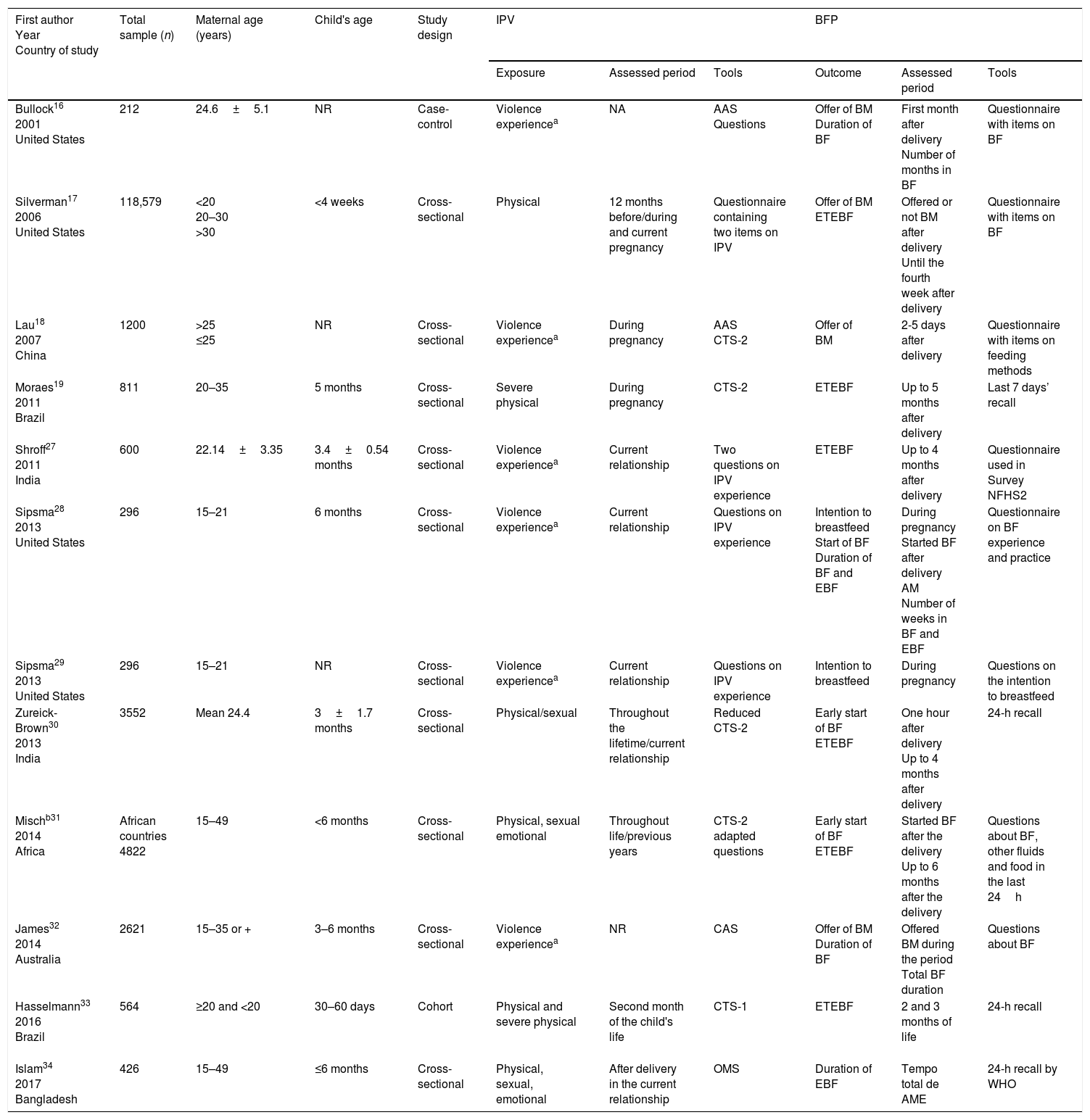

The overall characteristics of the articles included in this review are shown in Table 1. Of the studies included in the final review, ten were cross-sectional,17–19,27–32,34 one was a case–control study,16 and only one was a prospective cohort study.33 The studies were published between 2001 and 2017. The age of the assessed children ranged from 2 days to 6 months. Four studies were carried out in the United States, two in India, two in Brazil, one in China, one in Australia, one in eight African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe), and one in Bangladesh. The studies’ sample size ranged from 212 to 118,579 participants.

General characteristics of the studies that evaluated the association between intimate partner violence and breastfeeding practices.

| First author Year Country of study | Total sample (n) | Maternal age (years) | Child's age | Study design | IPV | BFP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Assessed period | Tools | Outcome | Assessed period | Tools | |||||

| Bullock16 2001 United States | 212 | 24.6±5.1 | NR | Case-control | Violence experiencea | NA | AAS Questions | Offer of BM Duration of BF | First month after delivery Number of months in BF | Questionnaire with items on BF |

| Silverman17 2006 United States | 118,579 | <20 20–30 >30 | <4 weeks | Cross-sectional | Physical | 12 months before/during and current pregnancy | Questionnaire containing two items on IPV | Offer of BM ETEBF | Offered or not BM after delivery Until the fourth week after delivery | Questionnaire with items on BF |

| Lau18 2007 China | 1200 | >25 ≤25 | NR | Cross-sectional | Violence experiencea | During pregnancy | AAS CTS-2 | Offer of BM | 2-5 days after delivery | Questionnaire with items on feeding methods |

| Moraes19 2011 Brazil | 811 | 20–35 | 5 months | Cross-sectional | Severe physical | During pregnancy | CTS-2 | ETEBF | Up to 5 months after delivery | Last 7 days’ recall |

| Shroff27 2011 India | 600 | 22.14±3.35 | 3.4±0.54 months | Cross-sectional | Violence experiencea | Current relationship | Two questions on IPV experience | ETEBF | Up to 4 months after delivery | Questionnaire used in Survey NFHS2 |

| Sipsma28 2013 United States | 296 | 15–21 | 6 months | Cross-sectional | Violence experiencea | Current relationship | Questions on IPV experience | Intention to breastfeed Start of BF Duration of BF and EBF | During pregnancy Started BF after delivery AM Number of weeks in BF and EBF | Questionnaire on BF experience and practice |

| Sipsma29 2013 United States | 296 | 15–21 | NR | Cross-sectional | Violence experiencea | Current relationship | Questions on IPV experience | Intention to breastfeed | During pregnancy | Questions on the intention to breastfeed |

| Zureick-Brown30 2013 India | 3552 | Mean 24.4 | 3±1.7 months | Cross-sectional | Physical/sexual | Throughout the lifetime/current relationship | Reduced CTS-2 | Early start of BF ETEBF | One hour after delivery Up to 4 months after delivery | 24-h recall |

| Mischb31 2014 Africa | African countries 4822 | 15–49 | <6 months | Cross-sectional | Physical, sexual emotional | Throughout life/previous years | CTS-2 adapted questions | Early start of BF ETEBF | Started BF after the delivery Up to 6 months after the delivery | Questions about BF, other fluids and food in the last 24h |

| James32 2014 Australia | 2621 | 15–35 or + | 3–6 months | Cross-sectional | Violence experiencea | NR | CAS | Offer of BM Duration of BF | Offered BM during the period Total BF duration | Questions about BF |

| Hasselmann33 2016 Brazil | 564 | ≥20 and <20 | 30–60 days | Cohort | Physical and severe physical | Second month of the child's life | CTS-1 | ETEBF | 2 and 3 months of life | 24-h recall |

| Islam34 2017 Bangladesh | 426 | 15–49 | ≤6 months | Cross-sectional | Physical, sexual, emotional | After delivery in the current relationship | OMS | Duration of EBF | Tempo total de AME | 24-h recall by WHO |

AAS, Abuse Assessment Screen; BF, breastfeeding; EBF, exclusive breastfeeding; CAS, Composite Abuse Scale; CTS-1, Conflict Tactics Scales; CTS-2, the revised Conflict Tactics Scale-2; ETEBF, early termination of exclusive breastfeeding; BM, breast milk; BFP, breastfeeding practices; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; WHO, World Health Organization; IPV, intimate partner violence.

IPV was investigated in different ways. Six studies investigated physical violence,17,19,30,31,33,34 whereas three assessed sexual violence30,31,34 and two studies evaluated emotional violence.31,34 The remaining seven considered the experience of violence, that is, to have been the victim of aggression, whether physical, sexual, or emotional.16,18,27–30,32 Only one article approached women as perpetrators of violence.29

Among the studies included in the review, two analyzed the intention to breastfeed,28,29 two assessed the start of breastfeeding,18,31 three evaluated the offer of breast milk,16,17,32 eight analyzed exclusive breastfeeding,17,19,27,28,30,31,33,34 and two assessed breastfeeding duration.16,28

To evaluate BFP, most studies (n=10) used some type of food registry or recall (Table 1, column 11).

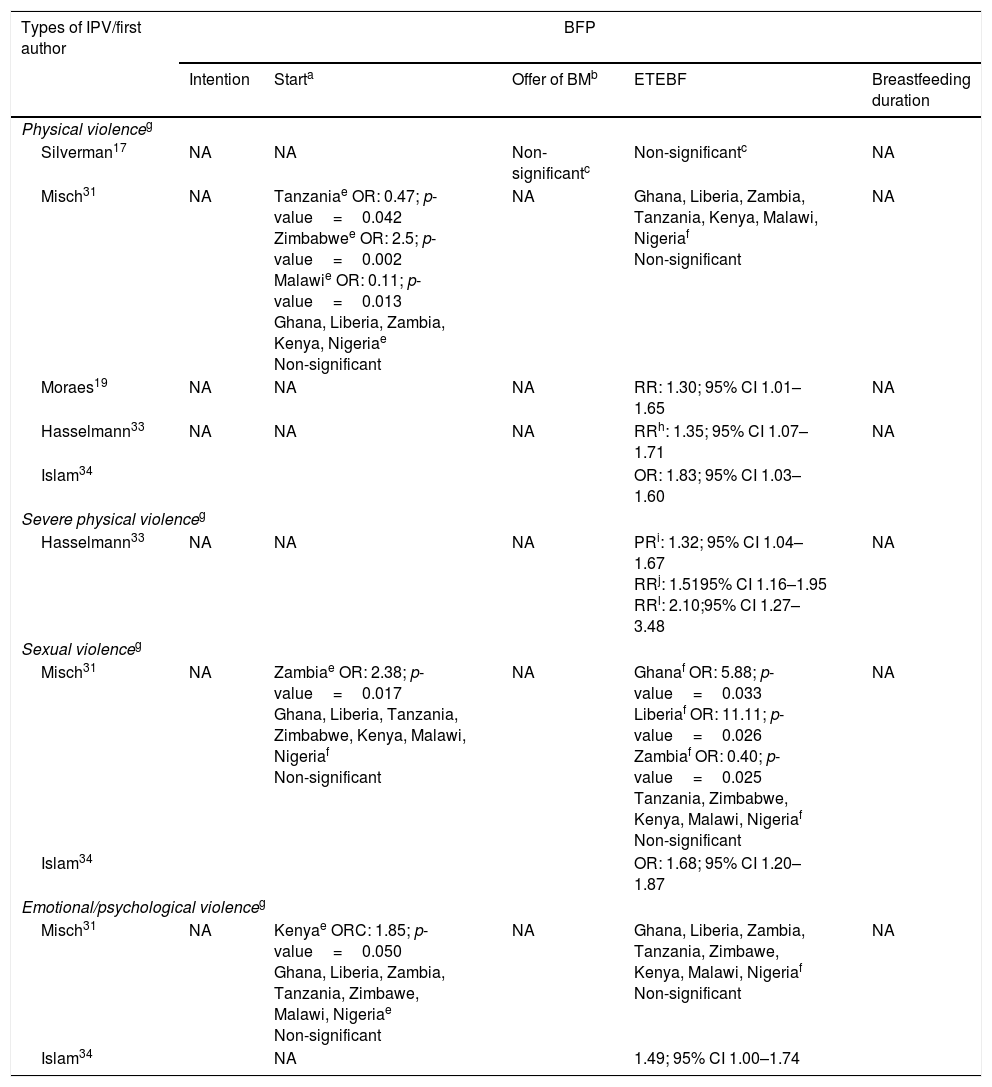

Association between IPV and BFPThe overall results of this systematic review are shown in Table 2. IPV was significantly associated with a lower breastfeeding intention in one study,29 early termination of exclusive breastfeeding in six studies,19,28,30,31,33,34 lower chance of breastfeeding initiation in two,18,31 and with duration of breastfeeding in one study.28 Contradictory results were observed in the study by Misch and Yount in different African countries.31 Physical IPV in Tanzania and sexual IPV in Zambia were associated with early initiation of breastfeeding (breastmilk offer in the first hour postpartum; OR 0.47, p=0.042) and with increased chances of exclusive breastfeeding (OR 0.40, p=0.025), respectively (Table 2, columns 3 and 5).

Main results of studies evaluating the association between IPV and breastfeeding practices of children in their first year of life.

| Types of IPV/first author | BFP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | Starta | Offer of BMb | ETEBF | Breastfeeding duration | |

| Physical violenceg | |||||

| Silverman17 | NA | NA | Non-significantc | Non-significantc | NA |

| Misch31 | NA | Tanzaniae OR: 0.47; p-value=0.042 Zimbabwee OR: 2.5; p-value=0.002 Malawie OR: 0.11; p-value=0.013 Ghana, Liberia, Zambia, Kenya, Nigeriae Non-significant | NA | Ghana, Liberia, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeriaf Non-significant | NA |

| Moraes19 | NA | NA | NA | RR: 1.30; 95% CI 1.01–1.65 | NA |

| Hasselmann33 | NA | NA | NA | RRh: 1.35; 95% CI 1.07–1.71 | NA |

| Islam34 | OR: 1.83; 95% CI 1.03–1.60 | ||||

| Severe physical violenceg | |||||

| Hasselmann33 | NA | NA | NA | PRi: 1.32; 95% CI 1.04–1.67 RRj: 1.5195% CI 1.16–1.95 RRl: 2.10;95% CI 1.27–3.48 | NA |

| Sexual violenceg | |||||

| Misch31 | NA | Zambiae OR: 2.38; p-value=0.017 Ghana, Liberia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeriaf Non-significant | NA | Ghanaf OR: 5.88; p-value=0.033 Liberiaf OR: 11.11; p-value=0.026 Zambiaf OR: 0.40; p-value=0.025 Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeriaf Non-significant | NA |

| Islam34 | OR: 1.68; 95% CI 1.20–1.87 | ||||

| Emotional/psychological violenceg | |||||

| Misch31 | NA | Kenyae ORC: 1.85; p-value=0.050 Ghana, Liberia, Zambia, Tanzania, Zimbawe, Malawi, Nigeriae Non-significant | NA | Ghana, Liberia, Zambia, Tanzania, Zimbawe, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeriaf Non-significant | NA |

| Islam34 | NA | 1.49; 95% CI 1.00–1.74 | |||

| Types of IPV/first author | BFP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | Starta | Offer of BMb | ETEBF | Duration of breastfeeding | |

| Physical/sexual violenceg | |||||

| Zureick-Brown30 | NA | NA | NA | OR: 0.74; 95% CI 0.58–0.95 | |

| Some experience of violenced,g | |||||

| Bullock16 | NA | NA | Non-significant | NA | Non-significant |

| Sipsma29 | OR: 0.37; 95% CI 0.16–0.84 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sipsma28 | Non-significant | NA | NA | OR: 3.29; 95% CI 1.81–6.01 | OR: 1.77; 95% CI 1.21–0.60 |

| James32 | NA | NA | Non-significant | NA | Non-significant |

| Lau18 | NA | OR: 1.84; 95% CI 1.16–2.91 | NA | NA | NA |

| Shroff27 | NA | NA | NA | Non-significant | NA |

| Zureick-Brown30 | NA | NA | NA | OR: 0.78; 95% CI 0.62–0.98 | NA |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ETEBF, early termination of exclusive breastfeeding; BM, breast milk; BFP, breastfeeding practices; NA, not applicable; IPV, intimate partner violence; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; PR, prevalence ratio.

Five studies did not observe a significant association between IPV and BFP. Physical violence was not significantly associated with breast milk offer, breastfeeding initiation, and the early termination of exclusive breastfeeding17,31; emotional violence was not associated with breastfeeding initiation and early termination of exclusive breastfeeding,31 and the experience of some type of violence was not associated with breast milk offer, breastfeeding duration, and early termination of exclusive breastfeeding.16,27,32

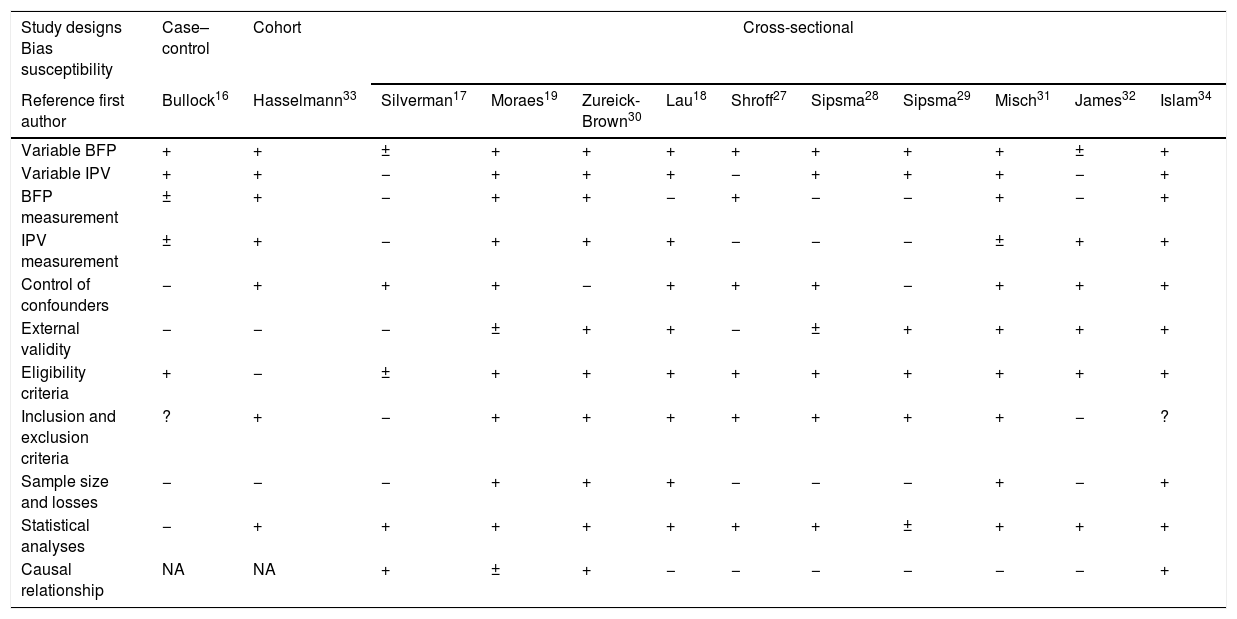

Bias susceptibilityTable 3 provides an individual description of bias susceptibility for each study. For the BFP variable, nine studies described how this variable was categorized and analyzed. Only six studies used the 24-h recall method to mention breast milk offer, breastfeeding initiation, early termination of exclusive breastfeeding, and/or breastfeeding duration.19,30,31,33,34

Bias susceptibility assessment.

| Study designs Bias susceptibility | Case–control | Cohort | Cross-sectional | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference first author | Bullock16 | Hasselmann33 | Silverman17 | Moraes19 | Zureick-Brown30 | Lau18 | Shroff27 | Sipsma28 | Sipsma29 | Misch31 | James32 | Islam34 |

| Variable BFP | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± | + |

| Variable IPV | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| BFP measurement | ± | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| IPV measurement | ± | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | ± | + | + |

| Control of confounders | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| External validity | − | − | − | ± | + | + | − | ± | + | + | + | + |

| Eligibility criteria | + | − | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | ? | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | ? |

| Sample size and losses | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Statistical analyses | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± | + | + | + |

| Causal relationship | NA | NA | + | ± | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

BFP, breastfeeding practices; IPV, intimate partner violence; +, yes; −, no; ±, partially; ?, unclear; NA, not applicable.

Regarding IPV, nine studies clearly showed how the variable was categorized and the forms of violence addressed separately.17,19,31–34 In order to measure IPV, six studies used complete validated instruments,18,19,30,32–34 and two studies used reduced or adapted CTS-2.30,31 The other studies used different measures, e.g., they asked questions related to the variable violence17,27–29 (Table 1, column 8).

Of the eight articles that used a validated instrument, six found a significant association between IPV and BFP.18,19,30,31,33,34 The quality varied between the studies; six were classified as having low bias susceptibility (they complied with 60% or more of the established criteria) based on the assessed items.18,19,30,31,33,34

DiscussionThis review presented evidence that IPV is associated with unfavorable BFP, as observed in eight of the 12 studies included in this review. Results such as the lower intention to breastfeed, the low probability to start breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of the child's life, and the higher chance of interrupting the exclusive breastfeeding were identified in couples where there is physical, sexual, and/or emotional violence. The results of the only prospective study demonstrate that children of women who suffered physical violence were at a higher risk of early termination of exclusive breastfeeding, both in the second month of life and in the following month, even after controlling for possible confounding factors. However, other studies did not find a significant association between IPV and BFP. Furthermore, in the study by Misch and Yount, maternal exposure to IPV was significantly related to early start of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding.

Conceptually, the possible routes of these associations are complex and still not fully established. Based on the literature, one can speculate on these associations in both directions. On the one hand, violence may increase the chances of risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol and drug abuse), increasing the probability of an adverse health outcome, including inadequate infant feeding practices.19,35 Moreover, violence may have consequences on the mother's emotional state and, consequently, on her willingness to care for the children or interact with them – the quality of mothering.30,36 Additionally, Klingelhafer37 and Dignam38 suggest that some partners believe there is a difference in their wives’ relationship with them and with the child during the breastfeeding period. Partners may consider the mother's breasts as belonging to them and, therefore, are not prepared to share them with the infant.39 According to Dignam,38 breastfeeding provides an intimate exchange between mother and child, bringing harmony, emotional closeness, skin sensitiveness to touch, and reciprocity. This relationship ultimately excludes the partner, who can see the child as a competitor for the woman's attention, and thus discourages breastfeeding and assumes an aggressive attitude toward the mother and the newborn. On the other hand, Levandovsky et al.40 suggest the possibility of a “compensatory hypothesis,” under which battered women try to compensate for the violence by giving more attention and responsiveness to the child. Similarly, a study by Kelly41 with Hispanic mothers living in the United States showed that abused women prioritize, protect, and care for their children in situations of violence.

Other studies show that the partner's support during breastfeeding is a significant factor for women's success in breastfeeding. However, partner support is less likely to occur in an abusive relationship.42 Women who feel more supported by their partners during the prenatal and postpartum periods have more confidence and self-esteem, and therefore are more prone to start and maintain breastfeeding.28,29,31

Additionally, there is a lack of studies that investigate violence perpetrated by women. Except for one study, IPV was investigated at some point in the woman's life, in the previous or current relationship and/or during pregnancy, and its consequences on BFP, thus demonstrating a gap on the knowledge of this aspect regarding the behavior of women as perpetrators of violence and its implications.

In general, regarding bias susceptibility, four studies received a negative evaluation, which may affect the validity of these studies’ results. These possible biases include the use of tools to identify BFP, categories of emotional violence together with physical and sexual analysis, use of non-validated tools to measure exposure and outcome, and adjustment of the analysis without considering confounding variables related to the exposure and outcome.

Most studies included in the present review assessed BFP through a 24-h recall (point measurement). From this perspective, it may be inadequate to evaluate, for instance, exclusive breastfeeding duration, since this method is intended to provide a scenario of current practices. The 24-h recall may generate an error in the exclusive breastfeeding estimation, as shown in the study by Greiner.43 Children who irregularly receive other fluids might not have consumed them the day before the research.

Exposure measurement varied across studies, including different scales to measure IPV, different cut-off points, and several types of relationships and exposure periods investigated. Another aspect that should be highlighted is related to the period during which the exposure was investigated. This review included studies that estimated lifelong exposure, during childhood, during pregnancy, in the postpartum, and in the past 12 months. Available studies show that IPV measurement can be attained through 20 different scales, which include items that assess only one type of violence, such as sexual violence or emotional abuse, or those that aim to assess more than one type of violence.44,45 Questions related to the validity and reliability of these scales, their objectives, the potential consequences, or the possible impacts on the results of studies that address the association of IPV with different results in the field of maternal and child nutrition, deserve reflection. As observed by Misch and Yount,31 the results might be valid, or they might have some degree of misclassification due, for instance, memory bias, misinterpretation of the question, or especially fear related to the consequences of disclosure.

Moreover, tools with specific questions about different forms and intensity of violence experienced by couples are more likely to capture a situation of violence than those that use a single question. In this perspective, the associations between maternal IPV victimization and BFP, for instance, may be over- or underestimated.

It is worth mentioning that most studies included in this review had a cross-sectional design, so there is a possible memory bias regarding questions to participants about exposure and practices in the past.46 Additionally, it is difficult to separate causes and effects, since the outcome and exposure prevalence rates are assessed simultaneously among individuals.46

Another important characteristic of the present study is that, although the search criteria included children in the first year of life, all the studies identified by the search were restricted to children aged 2 days to 6 months of age. It is likely that the studies focused on early infant feeding practices, such as the start of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding, given the international consensus on its importance and recommendation to ensure children's adequate growth and development.2,7

It is noteworthy that, despite efforts to research and consider all the studies, it was not possible to identify studies in the gray literature, aiming to minimize the potential effects of publication bias.

The strategies to promote breastfeeding and infant feeding practices, as well as the prevention of IPV, are challenges yet to be overcome. Most interventions can be carried out at healthcare facilities, where women's primary care takes place, such as prenatal, obstetrical, and gynecological clinics.47,48

Other intervention categories are those directly applied against the violence perpetrator. This type of intervention is generally carried out as part of the penalty aimed at domestic violence perpetrators.49 These existing interventions may be offered directly to men on the perspectives of gender differences, abuse, control, and moments of anger, as well as treatment for drug and alcohol abuse.50

Future studies should focus not only on adequate BFP, but also on the adequate introduction of complementary feeding and infant feeding, given its importance for development and growth in childhood and adulthood. Also, to improve the current understanding of the association between IPV and infant feeding practices, further research requires prospective studies, carried out in broader contexts, with the use of validated tools and robust analyses that address both genders, given the complexity of this association.

Violence is a complex phenomenon involving all family members and, therefore, intervention programs against domestic violence need to be encouraged, among victims and perpetrators, as an excellent way of achieving a change of thought and social behavior about violence. The main objective of these programs should be to prevent gender-based violence, increase the confidence of women, and empower them against abusive relationships and their consequences. Furthermore, studies that investigate the specific role of each type of violence in the start and duration of breastfeeding help to create more specific strategies to be used in healthcare. On a practical level, improving women's self-esteem and confidence during the prenatal and postpartum periods can have beneficial effects at different levels. This would not only be a way to break the cycle of violence, but would also help improve women's attitudes toward themselves and their babies, and would eventually have a positive effect on breastfeeding. Thus, understanding the context and motivations of mothers who are victims of violence and breastfeed their children can be useful for providing counseling and support to all victimized mothers, in addition to considering these factors when planning child feeding and nutrition policies and programs.

Finally, it is important to understand how the effects of IPV can vary among cultural scenarios and the availability and quality of prenatal care, popular beliefs about breastfeeding, and the existing public health efforts to promote breastfeeding. These contextual differences may also help explain why the results vary from country to country.

FundingCarlos Chagas Filho Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ); Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mezzavilla RS, Ferreira MF, Curioni CC, Lindsay AC, Hasselmann MH. Intimate partner violence and breastfeeding practices: a systematic review of observational studies. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:226–37.