To identify delays in the health care system experienced by children and adolescents and young adults (AYA; aged 0–29 years) with osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma using information from the Brazilian hospital-based cancer registries.

MethodsPatient data were extracted from 161 Brazilian hospital-based cancer registries between 2007 and 2011. Hospital, diagnosis, and treatment delays were analyzed in patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis. Referral, hospital, and health care delays were calculated for patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis. The time interval was measured in days.

ResultsThere was no difference between genders in overall delays. All delays increased at older ages. Patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis had the longest hospital delay when compared to patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis before first contact with the cancer center. Patients with Ewing sarcoma had longer referral and health care delays than those with osteosarcoma who had a previous histopathological diagnosis before first contact with the cancer center. The North and Northeast regions had the longest diagnosis delay, while the Northeast and Southeast regions had the longest treatment delay.

ConclusionHealth care delay among patients with a previous diagnosis was longer, and was probably associated with the time taken for to referral to cancer centers. Patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis had longer hospital delays, which could be associated with possible difficulties regarding demand and high-cost procedures. Despite limitations, this study helps provide initial knowledge about the healthcare pathway delays for patients with bone cancer inside several Brazilian hospitals.

Identificar atrasos no sistema de saúde em crianças e adolescentes e adultos jovens (AAJ; até 29 anos) com osteossarcoma e sarcoma de Ewing com informações dos registros de câncer de base hospitalar do Brasil.

MétodosOs dados dos pacientes foram extraídos de 161 registros de câncer de base hospitalar brasileiros entre 2007 e 2011. Os atrasos no hospital, no diagnóstico e no tratamento foram analisados em pacientes sem um diagnóstico histopatológico anterior. Os atrasos no encaminhamento, no hospital e no sistema de saúde foram calculados para pacientes com diagnóstico histopatológico anterior. O intervalo de tempo foi medido em dias.

ResultadosNão houve diferença entre os sexos nos atrasos em geral. Todos os atrasos aumentaram na faixa etária mais velha. Os pacientes sem um diagnóstico histopatológico anterior apresentaram o atraso hospitalar mais longo em comparação com os pacientes com diagnóstico histopatológico anterior antes do primeiro contato com o centro de câncer. Os pacientes com sarcoma de Ewing apresentaram atrasos no encaminhamento e no sistema de saúde mais longos do que os com osteossarcoma, que apresentaram diagnóstico histopatológico anterior antes do primeiro contato com o centro oncológico. As regiões Norte e Nordeste apresentaram o atraso mais longo no diagnóstico, ao passo que as regiões Nordeste e Sul apresentaram o atraso mais longo no tratamento.

ConclusãoO atraso no sistema de saúde entre os pacientes com diagnóstico anterior foi maior e provavelmente associado ao tempo de encaminhamento para os centros oncológicos. Os pacientes sem um diagnóstico histopatológico anterior apresentaram atrasos mais longos no hospital, o que pode ser associado a possíveis dificuldades com relação à demanda e aos procedimentos de alto custo. Apesar das limitações, nosso estudo ajuda a fornecer um conhecimento inicial sobre os atrasos no sistema de saúde para tratamento de pacientes com câncer em vários hospitais brasileiros.

Bone cancers are relatively uncommon, accounting for only 0.2% of human neoplasia. However, young patients are more affected, and the etiology is unknown.1 Approximately 60% of primary bone cancer occurs in people younger than 45 years.2 The most incident morphological subtypes of bone cancer among children and adolescents and young adults (AYA) are osteosarcoma (OS) and Ewing sarcoma (ES).1,3

In Brazil, two cooperative groups have well-established treatment protocols for these subgroups of bone cancer, which were created through an initiative developed by a group of pediatric oncologists: the Brazilian Osteosarcoma Treatment Group (BOTG) and Brazilian Collaborative Study Group for Ewing Sarcoma Family Tumors (Grupo de Estudo Colaborativo Brasileiro para Tratamento dos Tumores da Família Sarcoma de Ewing – EWING1).4,5

Since 1989, all of the Brazilian population is entitled to free health care at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels through the national health system (Sistema Único de Saude [SUS]). Primary care is composed of units such as the Family Health Program created in 1994 and emergency care units. A patient with suspicion of cancer should be referred to a specialized center (secondary level) where high-cost procedures are performed, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and biopsy, if necessary. Tertiary care includes specialized hospital and treatment centers where patients should receive therapy from a multidisciplinary team.6–8

Some pediatric oncology centers have adopted this pathway and receive patients only after a diagnosis is made, while others receive patients when there are suspicious symptoms. There is no regular procedure or care pathway for children with cancer in Brazil; however, the care pathway may be influenced by several factors. The patient's family's involvement in the health care system is very significant because they are the ones who recognize the first symptoms of cancer.9 Moreover, the professional's knowledge, the primary and secondary care infrastructure, as well as the distance from the patient's residence to specialized centers may also be associated with delays in the cancer care treatment pathway.8

Delays in the health care system are an important concern due to the association between socioeconomic status and health care providers, as well as biologic tumor characteristics.10–13

The term “delay” is used to designate the time interval, which may differ for each study. There is no consensus about the exact number of days that should be considered a delay.9 Different definitions of delay related to the health care system are used in literature, including patient delay (interval between the first symptoms and the first medical contact); first diagnosis delay (interval between the first symptoms and a first diagnosis); referral delay; doctor delay (interval between the first medical contact and a precise diagnosis); hospital delay; and treatment delay.9,11,14–16

The longest diagnosis delays are reported for bone cancer, carcinomas, and retinoblastoma.11,16 Some studies in Brazil have described patient delays among those with bone tumors.12,17 The mean time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis in patients registered at BOTG was 129 days (median: 90 days) and was not correlated with the presence of metastases, tumor size, or survival.4 These data suggest that the stage of disease depends more on the biological properties of the tumor than on late diagnosis.

The aim of this study was to identify delays in the health care system for children and AYA (0–29 years) with OS and ES, using information from Brazilian hospital-based cancer registries (HBCRs).

Materials and methodsAge group was classified as 0–14 years (children) and 15–29 years (AYA). As it is known, the term AYA is not clearly defined in literature. Among publications, the definition for adolescents and young adults with cancer most used in the literature is between 15 and 29 years.

Patient data were extracted from 161 Brazilian HBCRs between 2007 and 2011.18 After downloading each of the databases, data was transferred into a database in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. NY, USA) to provide statistical analysis. Patient information from each registry included gender, age group (0–14 years; 15–19 years; and 20–29 years); subtype of bone cancer (OS; ES); previous histopathological diagnosis (yes or no); date of results of histopathological diagnosis performed before the first consultation at a cancer center; data of first medical contact at the cancer center, date of results of histopathological diagnosis performed at a cancer center; and date of treatment initiation at a cancer center. Unfortunately, information on the onset of symptoms was not available, so it was not possible to evaluate patient delay.

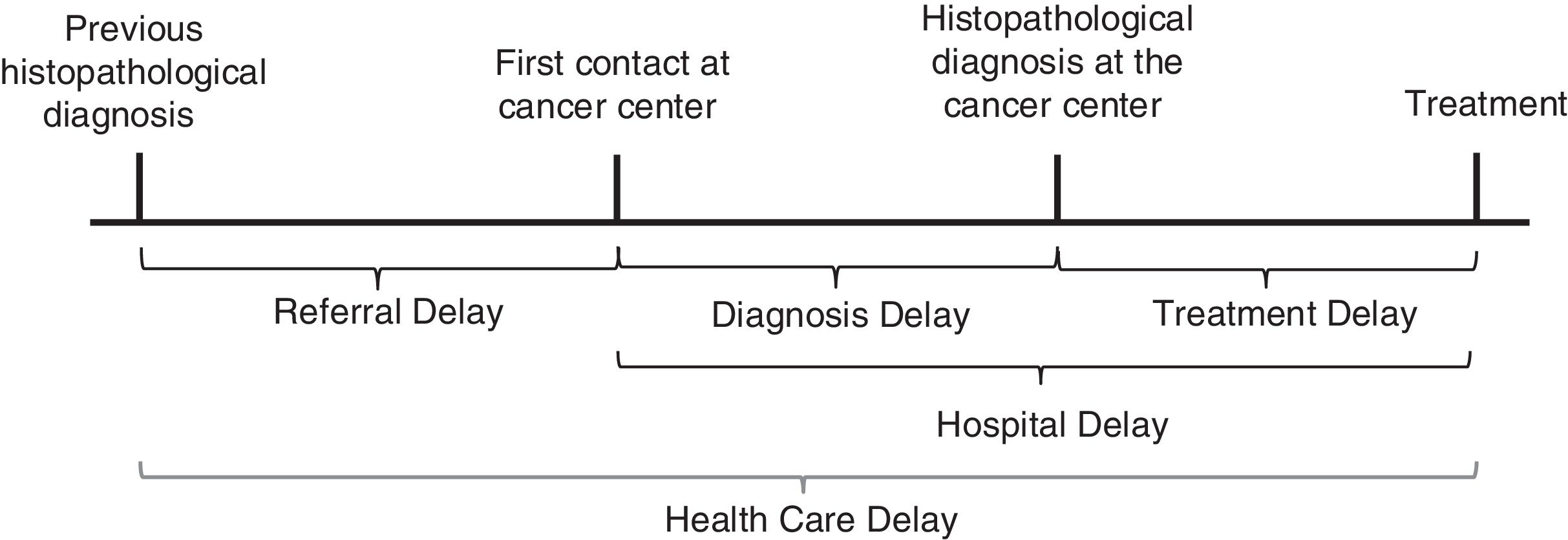

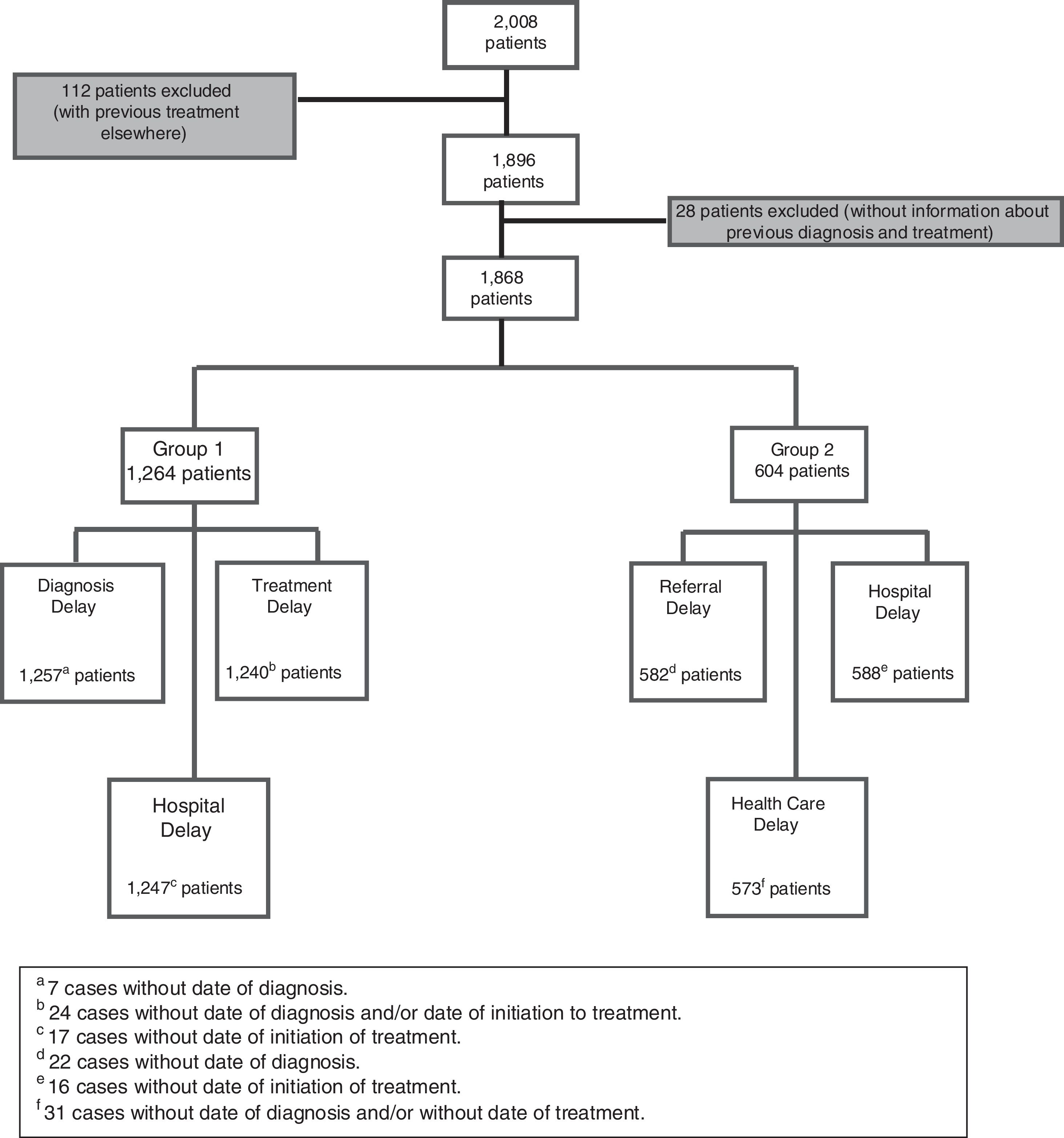

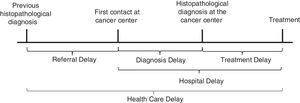

The term ‘delay’ was used to designate the time interval measured in days without judgment of delay.9,16 Referral delay was defined as the time between the date of the previous histopathological diagnosis and first contact at the cancer center. Diagnosis delay was defined as the time between the first medical contact and the histopathological diagnosis performed at the cancer center. Treatment delay was defined as the time between the histopathological diagnosis done at the cancer center and the initiation of treatment. Hospital delay was defined as the time between the date of the first contact at the cancer center and treatment initiation at a cancer center. Health care system delay was defined as the time between the previous histopathological diagnosis performed elsewhere and the initiation of treatment at the cancer center (Fig. 1). There were 2008 cases of children, adolescents, and young adults (0–29 years) selected across the five main geographic regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Midwest). Patients who had undergone any treatment (except histopathological diagnosis) elsewhere were excluded. This study also excluded cases with missing information regarding previous diagnosis or treatment. There were 1868 eligible cases. Patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 included patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis, and Group 2 included patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis (biopsy) before their first contact at a cancer center.

Diagnosis delay in cancer care pathways, adapted from Dang-Tan and Franco.9

Diagnosis and treatment delays were calculated for the patients in Group 1 only. Referral and health care system delay were calculated in Group 2 only. Both Groups 1 and 2 were included in the analysis of hospital delay. The number of patients experiencing each type of delay differed due to missing data or errors in the data entry (Fig. 2).

The median and 25th and 75th percentiles of time (in days) were calculated for delay overall and among the following categories: gender, age group, bone cancer subtype, and Brazilian geographic region. SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. NY, USA) was used to test the equality of each delay within subgroups of selected variables (sex, age group, type of tumor, and region) using the Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests. The significance level was considered as p<0.05.

This study was approved (1.368.120) by the Research Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA).

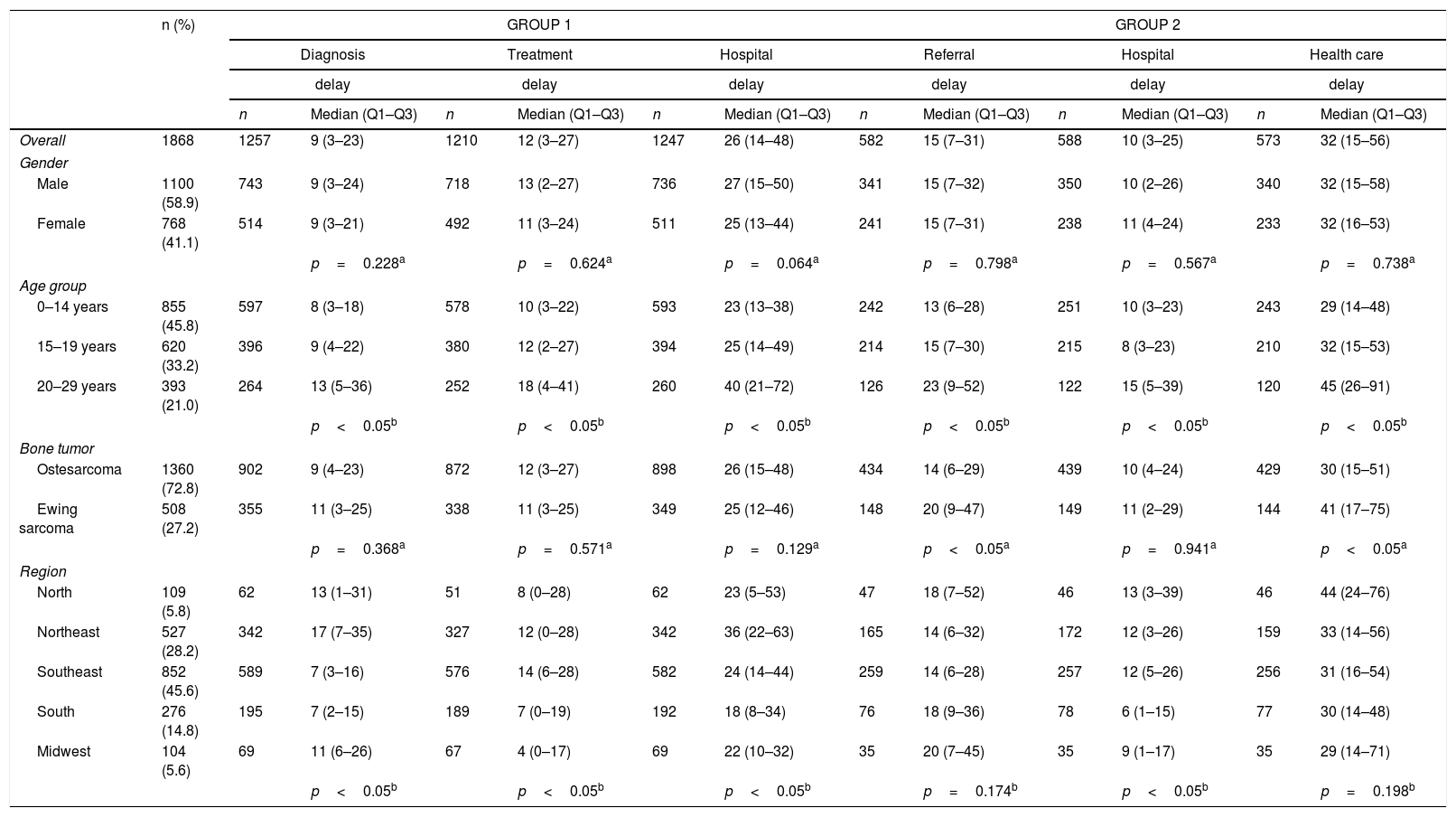

ResultsA majority of the 1868 patients were male (58.9%), aged between 0 and 14 years (45.8%) with a diagnosis of osteosarcoma (72.8%), without a previous histopathological diagnosis (67.7%), and were treated in the Southeast region (45.6%; Table 1).

Number and distribution of all cases included in study; median delays, 25th and 75th percentiles (in days) according to clinical and sociodemographic variables for both groups of patients.

| n (%) | GROUP 1 | GROUP 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Treatment | Hospital | Referral | Hospital | Health care | ||||||||

| delay | delay | delay | delay | delay | delay | ||||||||

| n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | n | Median (Q1–Q3) | ||

| Overall | 1868 | 1257 | 9 (3–23) | 1210 | 12 (3–27) | 1247 | 26 (14–48) | 582 | 15 (7–31) | 588 | 10 (3–25) | 573 | 32 (15–56) |

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 1100 (58.9) | 743 | 9 (3–24) | 718 | 13 (2–27) | 736 | 27 (15–50) | 341 | 15 (7–32) | 350 | 10 (2–26) | 340 | 32 (15–58) |

| Female | 768 (41.1) | 514 | 9 (3–21) | 492 | 11 (3–24) | 511 | 25 (13–44) | 241 | 15 (7–31) | 238 | 11 (4–24) | 233 | 32 (16–53) |

| p=0.228a | p=0.624a | p=0.064a | p=0.798a | p=0.567a | p=0.738a | ||||||||

| Age group | |||||||||||||

| 0–14 years | 855 (45.8) | 597 | 8 (3–18) | 578 | 10 (3–22) | 593 | 23 (13–38) | 242 | 13 (6–28) | 251 | 10 (3–23) | 243 | 29 (14–48) |

| 15–19 years | 620 (33.2) | 396 | 9 (4–22) | 380 | 12 (2–27) | 394 | 25 (14–49) | 214 | 15 (7–30) | 215 | 8 (3–23) | 210 | 32 (15–53) |

| 20–29 years | 393 (21.0) | 264 | 13 (5–36) | 252 | 18 (4–41) | 260 | 40 (21–72) | 126 | 23 (9–52) | 122 | 15 (5–39) | 120 | 45 (26–91) |

| p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p<0.05b | ||||||||

| Bone tumor | |||||||||||||

| Ostesarcoma | 1360 (72.8) | 902 | 9 (4–23) | 872 | 12 (3–27) | 898 | 26 (15–48) | 434 | 14 (6–29) | 439 | 10 (4–24) | 429 | 30 (15–51) |

| Ewing sarcoma | 508 (27.2) | 355 | 11 (3–25) | 338 | 11 (3–25) | 349 | 25 (12–46) | 148 | 20 (9–47) | 149 | 11 (2–29) | 144 | 41 (17–75) |

| p=0.368a | p=0.571a | p=0.129a | p<0.05a | p=0.941a | p<0.05a | ||||||||

| Region | |||||||||||||

| North | 109 (5.8) | 62 | 13 (1–31) | 51 | 8 (0–28) | 62 | 23 (5–53) | 47 | 18 (7–52) | 46 | 13 (3–39) | 46 | 44 (24–76) |

| Northeast | 527 (28.2) | 342 | 17 (7–35) | 327 | 12 (0–28) | 342 | 36 (22–63) | 165 | 14 (6–32) | 172 | 12 (3–26) | 159 | 33 (14–56) |

| Southeast | 852 (45.6) | 589 | 7 (3–16) | 576 | 14 (6–28) | 582 | 24 (14–44) | 259 | 14 (6–28) | 257 | 12 (5–26) | 256 | 31 (16–54) |

| South | 276 (14.8) | 195 | 7 (2–15) | 189 | 7 (0–19) | 192 | 18 (8–34) | 76 | 18 (9–36) | 78 | 6 (1–15) | 77 | 30 (14–48) |

| Midwest | 104 (5.6) | 69 | 11 (6–26) | 67 | 4 (0–17) | 69 | 22 (10–32) | 35 | 20 (7–45) | 35 | 9 (1–17) | 35 | 29 (14–71) |

| p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p<0.05b | p=0.174b | p<0.05b | p=0.198b | ||||||||

Group 1, patients without previous diagnosis; Group 2, patients with a previous diagnosis.

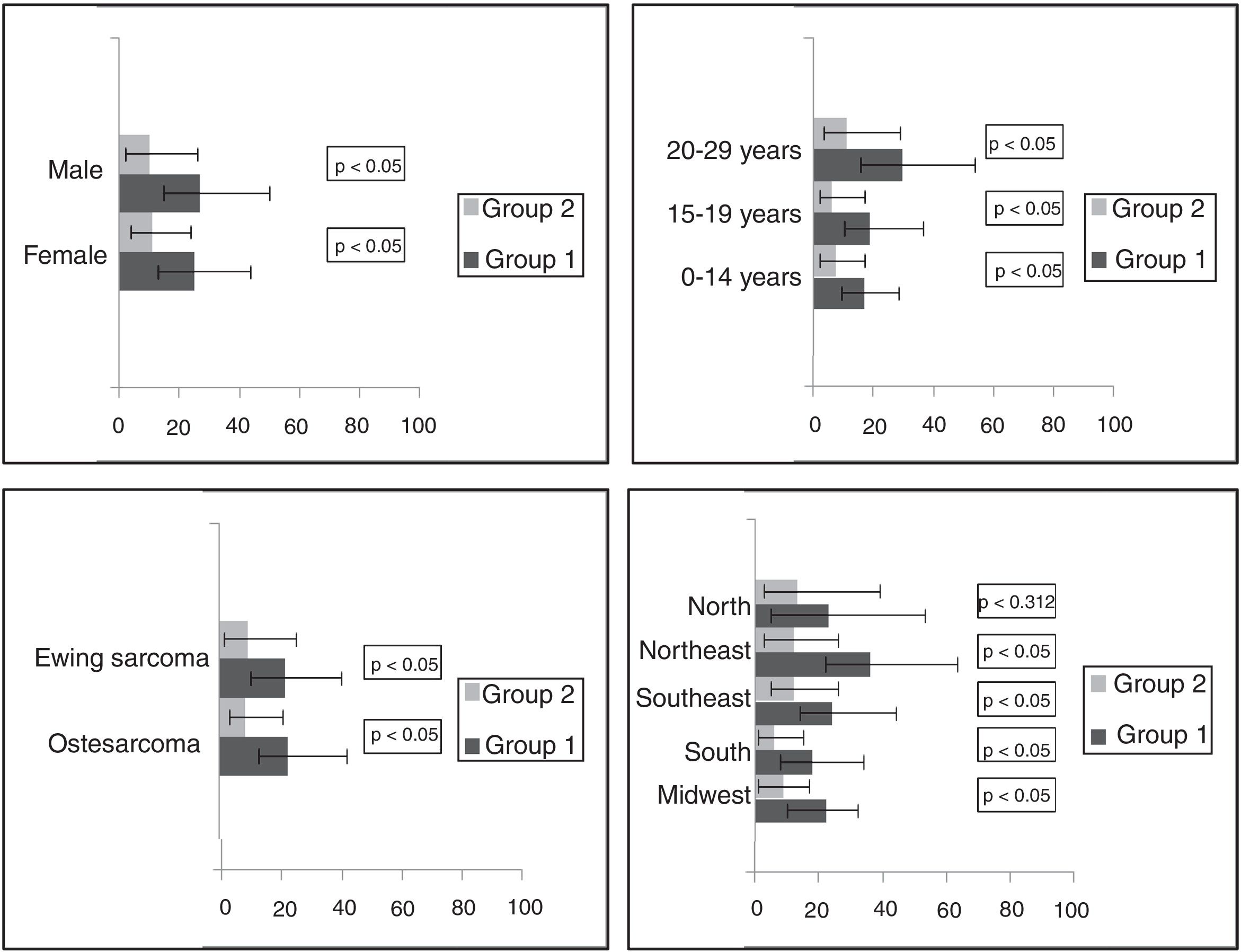

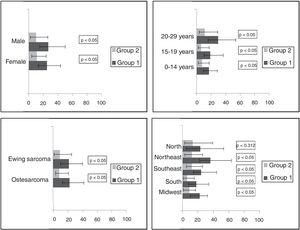

The distribution of delay times was expressed as the median and 25th and 75th percentiles for delays according to gender, age group, bone tumor subtype, and Brazilian geographic region, which can be seen in Table 1. In the overall analysis, there was no difference in delays between genders. There were statistically significant differences in all delays according to age. Patients aged 20–29 years had the longest delays.

There were differences among diagnosis and treatment delays between Brazilian geographic regions. The Northeast had the longest diagnosis delay, while the Southeast had the longest treatment delay (Table 1). In Group 2 (with previous histopathological diagnosis), patients with Ewing sarcoma had a longer referral and health care delay than those with osteosarcoma (Table 1). Patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis (Group 1) had a longer hospital delay than patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis that was performed before their first contact at a cancer center (Group 2; Fig. 3).

DiscussionUnderstanding the determinants along the cancer care pathway is essential to improve strategies that minimize delays. The pathway to cancer care is often not straightforward and includes the onset of first symptoms, first investigation, referral to a cancer center, definitive diagnosis, and the initiation of treatment.19 The present study's pathway starts after the histopathologic diagnosis or when the patient reaches the cancer center, so that it is possible to calculate referral, diagnosis, treatment, hospital, and health care system delays as described in Fig. 1. It was not possible to analyze delays regarding the first suspicions of cancer both by family members (or patients) and primary attending physicians. Therefore, an analysis of the complete care pathway was not possible, jeopardizing the results. However, health care system delays may be related to bureaucracies associated with providers, such as administrative processes or the diagnostic infrastructure.

In Brazil, as well as other developing countries, referral delay can be affected by the health care system taking too long to schedule a medical appointment at a hospital for tertiary attention. Diagnosis delay can be associated with errors that occur in the differential diagnosis in a primary health center or a delay in performing a biopsy. Treatment delays may be due to the number of hospital beds available and hospitalization, as well as the number of specialized professionals at a hospital.13,17

The lack of standardized time intervals used in different studies leads to several controversies that make comparisons with other studies in the literature difficult. Diagnosis or patient delay is commonly calculated as the time from the first symptoms to diagnosis in several studies.11,17,20 The impact of a diagnosis delay on the prognosis of children and adolescents with cancer is still controversial. In some types of tumors (e.g., retinoblastoma, Wilms’ tumor), a shorter interval between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis reflects a better prognosis.21,22 Patient delay (or time from the first symptoms to diagnosis) in children and adolescents with bone tumors has not been associated with lower survival rates.4,20,23

Young adults aged 20–29 years had significantly longer delays. A previous study demonstrated that most patients older than 18 years in Brazil are treated in medical oncology wards.24 As described in Canada, adolescents treated at adult centers report longer waiting times between health care events.10 All delays were higher in AYA patients, which can in part be justified by the number of patients and a lack of beds in medical oncology wards. The longer diagnosis delay in AYA also may be associated with difficulties in histopathological diagnosis due to the rarity of bone tumors in this age group.25 Bleyer suggests that one of the major factors in longer delays for AYA is their increasing autonomy over their own healthcare decisions.26

The population's access to healthcare has increased greatly in the past 30 years since the creation of the SUS in Brazil. The data were taken almost entirely from the HBCRs of institutions linked to the SUS. The country is divided into five geographical regions, which have differences in demographic, economic, social, cultural, and health conditions. The Brazilian health system's challenges include the control of costs and access to comprehensive care, and coordination with primary health care. Socioeconomic and other disparities among regions are still large, affecting the health care system.6–8 Moreover, previous studies demonstrated a deficit in access to cancer treatment for children and adolescents living in the North, where patients may have to travel long distances to access specialized treatment. Many patients and their families have to move to receive treatment for their disease, and may provide false information to facilitate access to specialized wards, reflecting the inequality between different regions.8,27

Among patients without a previous histopathological diagnosis, the longest diagnosis delay occurred in the Northeast region. Bone tumors frequently require diagnostic tests in specialized diagnosis centers before the first treatment can be administered. The availability of equipment to perform CT scans differs among regions (North and Northeast, 0.7/100,000 inhabitants; Southeast, 0.9/100,000; and South, 1.4/100,000). Treatment and hospital delays were longer in the Southeast and Northeast regions. The South region had the shortest hospital delay in both patient groups. The number of hospital beds could affect delays in patient treatment. The Southeast region, which is the most populated, had the lowest number of beds per inhabitant, while the South region had the highest number of beds.28

Hospital delay was analyzed in both patient groups and there was a significant difference in overall delay. Patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis had a shorter time from the first contact at a cancer center to starting treatment, except in the North region. Despite the fact that treatment starts sooner, it is well known that initial diagnosis in a specialized cancer center can improve survival. Biopsy is a fundamental step to adequate treatment for bone tumors. Inappropriate biopsy techniques in bone tumors can predispose to local relapse. Biopsies should be done with sufficient material to reach a precise diagnosis.29,30 Therefore, specialized centers may request slide revision in those patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis. This can delay the onset of treatment due to a longer waiting time, although it is important to avoid misdiagnosis.

The median overall diagnosis delay (nine days) and treatment delay (12 days) were slightly higher than in Canada (four and seven days, respectively), but lower than in developing countries such as Nigeria (40 days of diagnosis delay).17,31

Among patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis of bone tumor, it was observed that the median overall referral delay was 15 days. In Canada, this interval was about 5–12 days.10,17 There were no differences in referral delays according to Brazilian regions, but there was a difference in referral delay among bone tumor subtypes. Patients with Ewing sarcoma experienced significantly longer delays; however, it is possible that this result is by chance. A major delay in Ewing sarcoma is described in several studies due to the difficultly in recognizing specific symptoms and the need for more expertise in histopathologic diagnosis.11,32 However, studies are necessary to investigate the details about differences in referral among subgroups of bone tumors.

There was a median of 32 days for health care delay, which ranged from 29 to 44 days according to Brazilian regions in patients with a previous histopathological diagnosis. In other words, treatment in a cancer center is delayed more than a month. Since the hospital delay in this group was not longer, it can be assumed that referral to cancer centers is possibly the main cause of this delay. Patients who were admitted to cancer centers without a histopathological diagnosis (Group 1) started treatment after a median of 26 days. This delay could be associated with possible difficulties in performing the biopsy due to demand that exceeds the capacity of surgical centers, and to a lack high-cost procedures performed at the hospitals. As previous discussed, biopsy performed at a cancer center is important to avoid misdiagnosis.

A major limitation of this study is that there is no information about first symptoms and the first medical contact before reaching the cancer center. Another major limitation is that this is a retrospective study, using secondary database information from 116 Brazilian HBCRs with incomplete records and with a possible lack of standardization regarding classification of variables. Despite these limitations, the authors believe that these data provide initial knowledge about the health care pathways among different Brazilian geographic regions and different age groups. Further studies are necessary to better investigation this issue.

FundingNVB has a scholarship from the National Institute of Cancer – INCA/MS. BDC has a scholar grant from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq, Brasília; #306291/2014-2) and from the Foundation for Support of Research, Rio de Janeiro (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, FAPERJ, Rio de Janeiro; #212989-2016).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the HBCR coordinators in Brazil who contributed to the datasets and made this work possible.

Please cite this article as: Balmant NV, Silva NP, Santos MO, Reis RS, Camargo B. Delays in the health care system for children, adolescents, and young adults with bone tumors in Brazil. J Pediatria (Rio J). 2019;95:744–51.